Advertisement

Review

Documentary 'Wojnarowicz' Captures The Urgent And Short Life Of An Activist Artist Battling AIDS

Editor's Note: This story contains a profanity that is spelled out because it is the official title of the film reviewed in the post.

Artist biographies tend to be genteel affairs, full of tweedy academics serenely explaining the subject’s importance in terms suitable for classroom viewing, where the slow camera pans over canvases set to classical music will inevitably lull at least half the students to sleep. (Art documentaries do a lot to keep kids from ever getting interested in art.) As one might surmise from its title, “Wojnarowicz: F--- You F-ggot F---er,” is in no danger of being shown in schools any time soon, which is in some ways a shame.

Director Chris McKim’s documentary portrait of the late multimedia artist and activist David Wojnarowicz is an electrifying movie experience. The film — which starts streaming this weekend at the Coolidge Corner Theatre’s Virtual Screening Room under the shortened, safe-for-work title “Wojnarowicz” — is a riveting recollection of an artistic eruption amid the crumbling ruins of New York City’s Lower East Side in the late 1970s. It’s about the birth of a confrontationally queer sensibility, the quiet tyranny of the donor class and the impossibility of separating politics from art, particularly during a pandemic that’s ravaging parts of the population deemed undesirable by people in power.

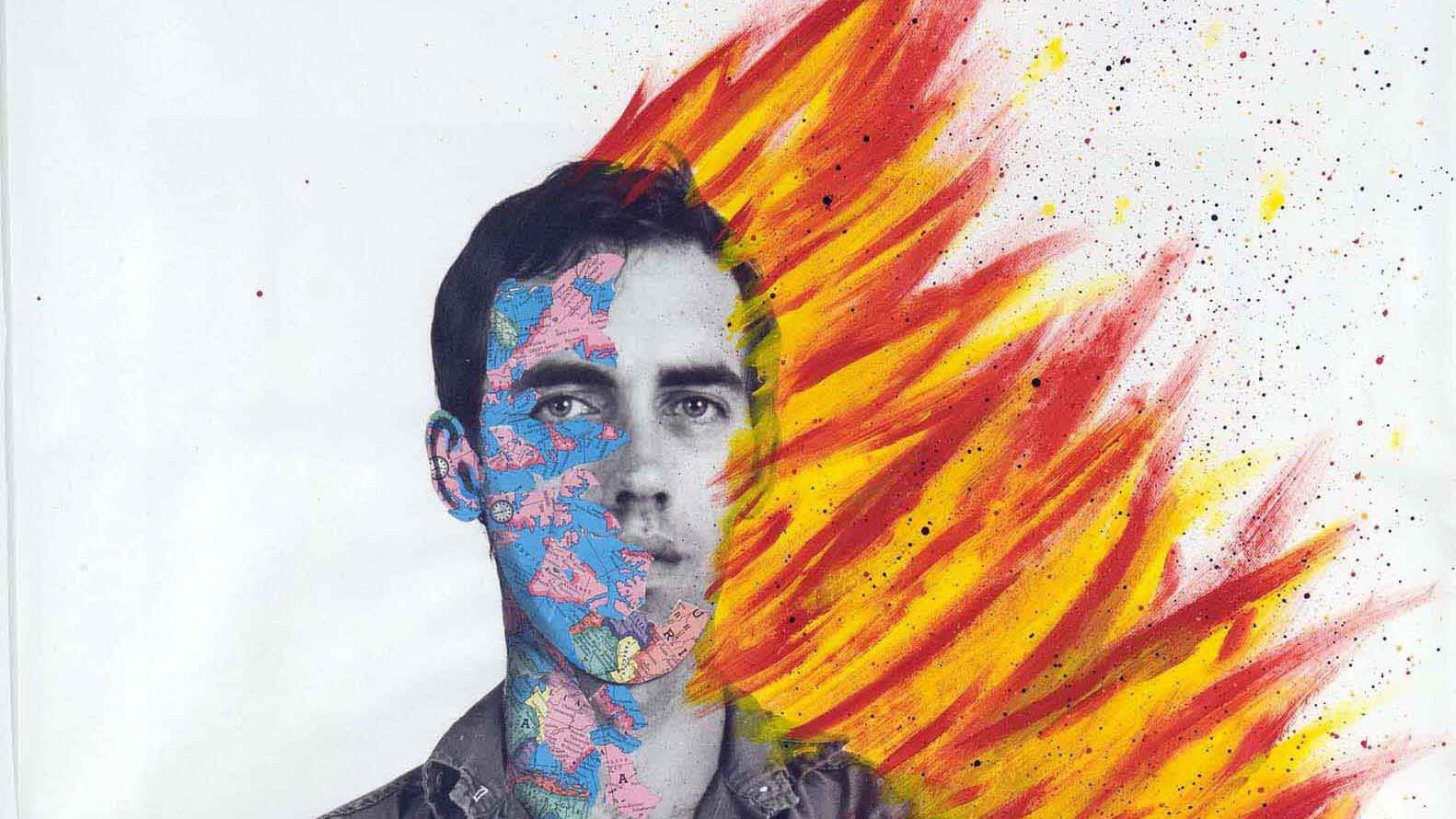

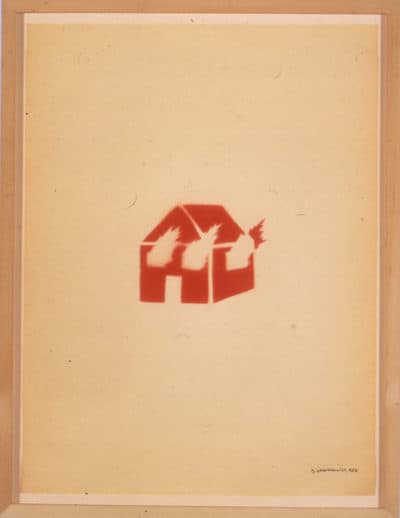

It’s also one of the few films I’ve seen about an artist that attempts to translate their sensibility into a cinematic vision. Wojarnowicz worked not just with paints and photography but also in stencils overlaid atop collages and text, as well as installations that included lighting effects and voice recordings. Brilliantly edited by Dave Stanke, the movie has been designed to look and sound like a Wojnarowicz exhibit. Culled from 200 hours of the artist’s audio cassette diaries, more than 20 hours of Super 8 film, 10,000 photographs and even his old answering machine message tapes, it’s all layered together into an expressionistic audio-visual roller-coaster with the same shouty, finger-jabbing immediacy of Wojarnowicz’s work.

The film begins in 1989, when Wojnarowicz was first fully drafted into the culture wars after his incendiary catalog essay contribution to the Artists Space exhibit “Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing” prompted the National Endowment for the Arts to withdraw a $10,000 grant for the show. Under pressure from the Bush White House, Jesse Helms and the usual suspects, the NEA argued the work was more political than artistic — as if there were some magical way one could scrub politics from art about the AIDS epidemic in America. (After considerable controversy, the grant was eventually reinstated.)

From there the film flashes back to Wojnarowicz's grim childhood, when he fled an abusive father in New Jersey and became an underage sex worker on the streets of New York City. A year spent with his sister in Paris got young David hooked on Jean Genet and Arthur Rimbaud, and the most entertaining segments of the movie chronicle his role upon returning in the gutter art renaissance of the Lower East Side. Beginning with what they called “uninvited installations,” Wojnarowicz and associates turned popular cruising spaces into studios and transformed junkie shooting galleries into art galleries. All of the sudden they were being written about in the New York Times and limos started rolling down past Avenue A to see what all the fuss was about.

The funniest of these sequences finds Wojnarowicz commissioned to create an installation in the basement of a lavish Manhattan brownstone owned by wealthy collectors Robert and Adriana Mnuchin (yes, the father and step-mother of Trump’s Treasury Secretary, Steve.) Wojnarowicz created a beautiful exhibit piled with heaps of stinky garbage he’d brought up from the Lower East Side, causing an insect infestation in his benefactors’ basement and prompting a hilariously anxious answering machine message from the art critic who arranged the deal. (“David wasn’t very good at having a career,” a friend points out.)

The contemporary interviews are kept off-screen, with the audio often overlaid against photographs of the speakers taken at the time. This preserves the film’s present-tense momentum while also allowing for hindsight as we hear from art historians, collectors and inevitably, Fran Lebowitz, our Herodotus of old decadent New York. Critic Carlo McCormick describes Wojnarowicz's style as “I’m not gay as in I love you, I’m queer as in f--- off.” Even his gentlest work had an edge of aggression, as when Wojnarowicz named a playful pastel of two men kissing in the ocean the string of obscene slurs that make up this movie’s subtitle.

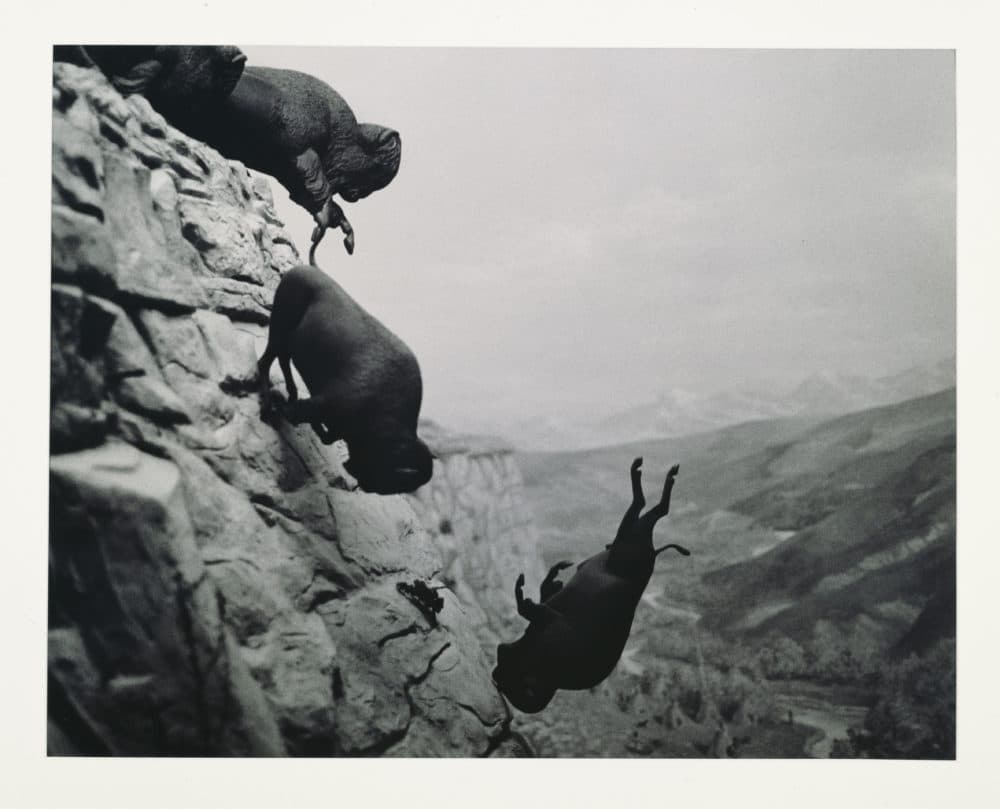

Things only get angrier and uglier when AIDS enters the picture, first claiming the life of his best friend Peter Hujar in 1987 and Wojnarowicz himself in 1992. Shortly before his passing, Wojarnowicz’s “Untitled (Falling Buffalos)” was used as the cover art and key promotional image for U2’s “One.” (This is how most people my age first encountered his work, back when the band was still cool and not a bunch of goofy old guys who work for Apple.) You’ve also probably seen photos of the instantly iconic leather jacket Wojnarowicz wore to an ACT UP protest, with a pink triangle on the back and the words “IF I DIE OF AIDS — FORGET BURIAL — JUST DROP MY BODY ON THE STEPS OF THE F.D.A.”

He spent his final years fighting — always fighting — this time, against the advice of friends, taking on the Reverend Donald Wildmon of the American Family Association, who had combed through one of Wojnarowicz catalogs, cropping and enlarging every image that could be considered obscene for use in a mass fundraiser mailing. The artist sued him for copyright infringement, winning only a dollar in damages but the verdict required that Wildmon send a letter to his flock admitting that he’d mischaracterized Wojnarowicz's work. Lebowitz claims this was a huge waste of time, for a dying man to battle bigots who will never learn.

Yet the dumber and more entrenched our country's culture wars become, the more I feel like Wojnarowicz's defiant spirit is more necessary than ever. Three decades ago he was asking questions about who in our society is allowed to determine what constitutes art, and which points of view are privileged while others get pushed out of the picture. This is not a movie that placates the audience or pats you on the back for watching. It leaves you provoked, riled-up and ready to start an argument. As art should.

“Wojnarowicz” is now streaming at the Coolidge Corner Theatre's Virtual Screening Room.