Advertisement

Why The People's Yellow Pages, A Relic Of '70s Counterculture, Still Resonates Today

It’s 1971 in Boston and revolution is in the air. A women’s group occupies a Harvard University building for 10 days. Blood spatters the pavement where the Boston Police broke up an anti-war rally downtown. Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young perform “Ohio,” their song about the Kent State massacre, at the Music Hall in Boston.

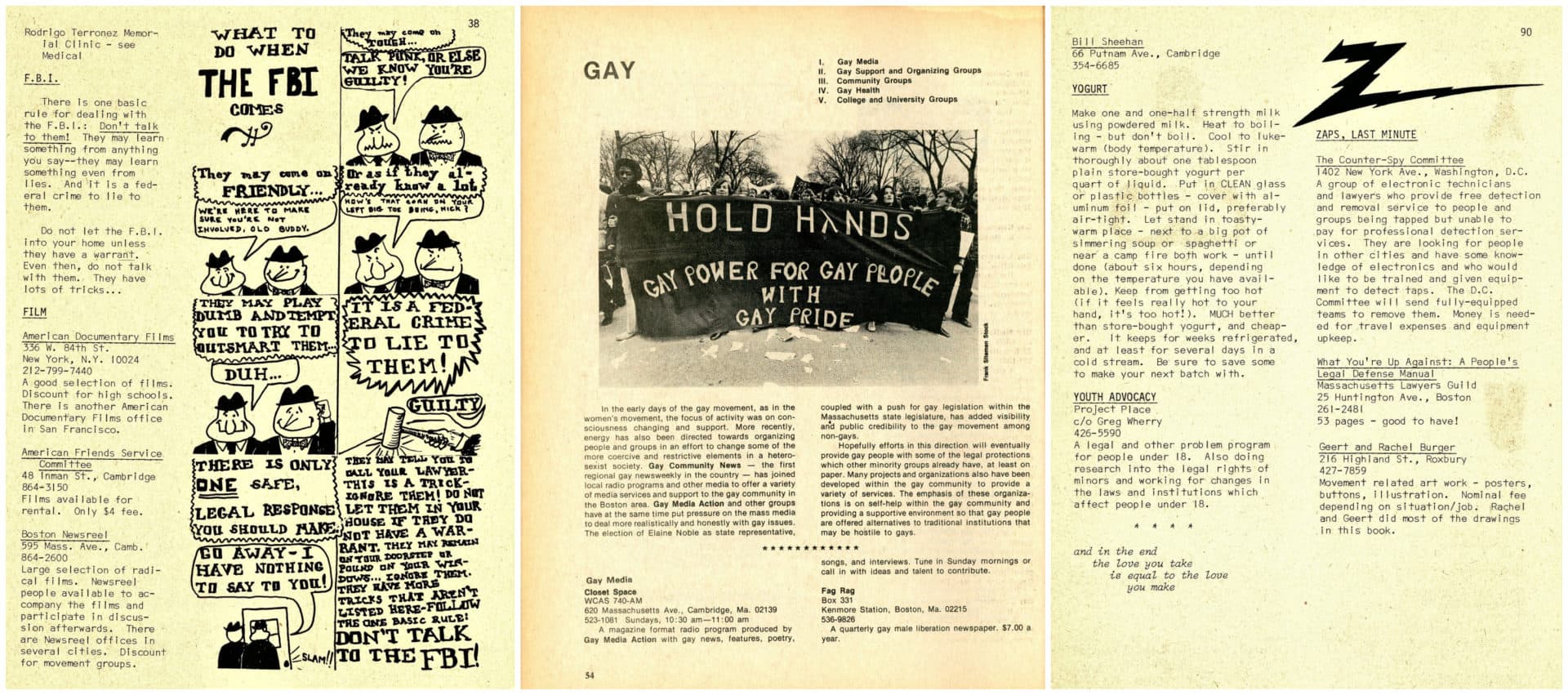

"There were a lot of liberation movements starting, certainly [the] Black power movement, women's movement, gay liberation movement," says Devon Davidson, who was a grad student living in Cambridge at the time. "And this was all in the midst of [an] increasingly active anti-war movement and draft resistors and young men burning draft cards."

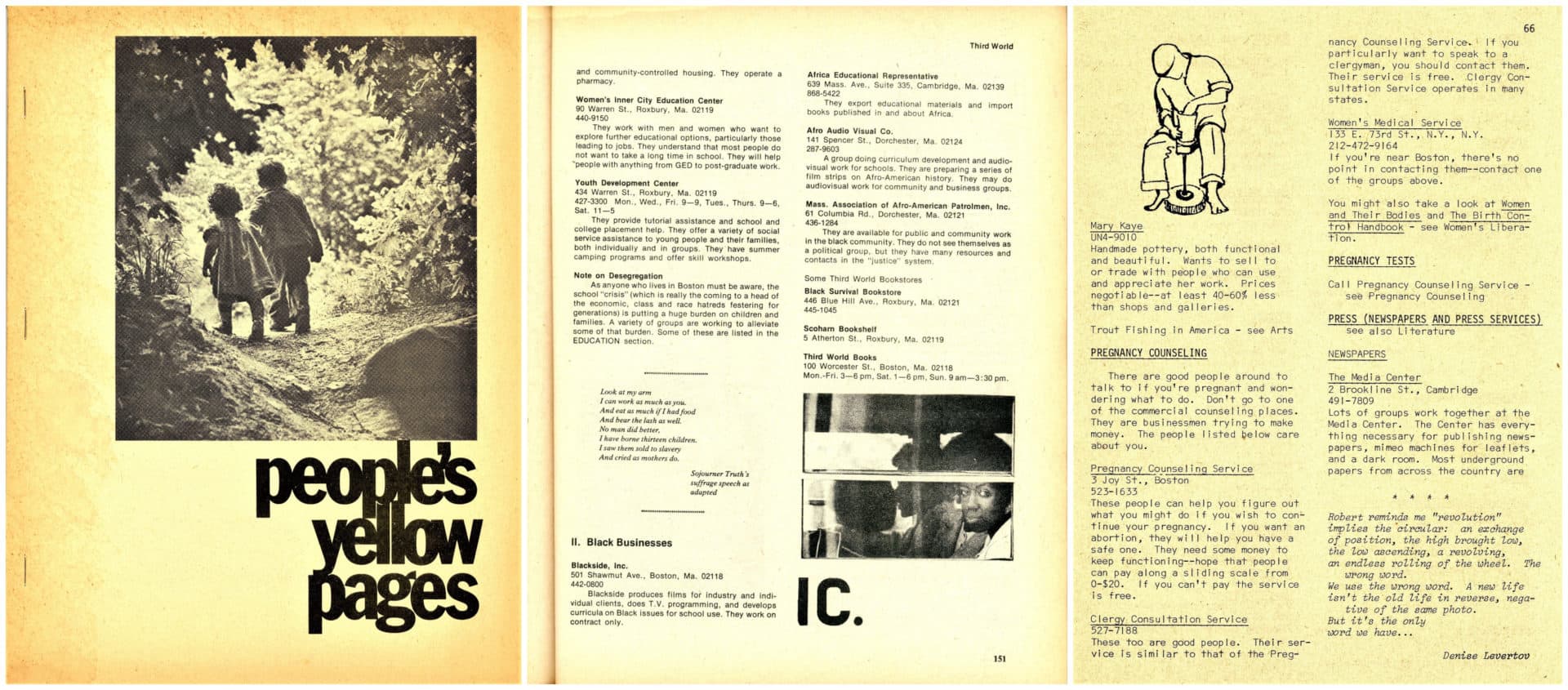

It was against this backdrop that the People's Yellow Pages was born. The nearly 100-page book was a modest proposal, at first: a regional directory of activist resources and mission-driven organizations. But the project proved massively successful in (largely white) leftwing circles, spurring similar efforts in other cities and lasting through the decade.

Over time, the People's Yellow Pages faded from memory. But it made its way into archives at Harvard and UMass Boston, a quirky relic from a bygone era. Fifty years later, it stands as a testament to grassroots ingenuity and the radical idealism of '70s counterculture.

It all began when Davidson and another young activist named Larry Casalino attended an anti-war meeting.

"A man stood up, and he said, 'You know what we need? We need a directory of places where we can keep our money out of the war economy,'" Davidson recalls.

That gave the pair an idea. What if local activists had a resource like the Yellow Pages — that thick tome the phone company delivered to your doorstep every year?

"There wasn’t the internet," Davidson explains. "If you wanted to know where a shoe repair place was in your neighborhood, you just looked it up in the Yellow Pages."

They set up shop at the Cambridge offices of Vocations for Social Change, a counseling center that Davidson helped found in 1970 under the auspices of the American Friends Service Committee, an activist Quaker organization.

"We would work there at night... poring through leaflets and posters, pamphlets, everything we could get our hands on that would give us some information about countercultural businesses and services in the Boston area," says People's Yellow Pages co-founder Larry Casalino.

Advertisement

The People's Yellow Pages became far more than an anti-war resource. It listed everything from women’s consciousness raising groups to free legal aid to recipes for yogurt.

"Yep, we were all making yogurt!" Davidson says with a laugh. It wasn't very good, she adds.

As quirky as it seems now, the People's Yellow Pages filled a void unique to the times, when certain resources were a lot harder to find — like where to get a safe abortion, or how to join local gay rights groups. And it was a runaway success. The first edition sold out so quickly, the group started work on a second edition before the year was up. They even created an instructional manual so that activists in other cities could start their own countercultural directories.

The resource had its limits, of course. "We were trying to be conscious of being anti-racist," Davidson says. But, since the People's Yellow Pages' creators were primarily white, college-educated and young, its audience was, too.

In later editions, the group took pains to include more resources serving communities of color. An editor's note in the 1976 edition describes the difficulty of this task. "Many people who are involved in alternative movements to effect change in their working, living, and social communities of Afro-Americans, Spanish, Asian-Americans, and Native Americans had never heard of the People's Yellow Pages," the editor writes. "A number of people involved in important issues did not want to be listed... They felt more time was necessary to get a better understanding of the motives and priorities of the People's Yellow Pages."

Davidson keeps a bound book containing the first three editions of the People’s Yellow Pages in her Cambridge apartment. Looking at it now, she remarks on how the social causes du jour are very much the same.

Racism. LGBTQ rights. The destruction of the environment. These issues, catalogued in the People’s Yellow Pages, still resonate today, as urgent as ever.

Some of the entries seem a little quaint now. There were instructions on growing your own mushrooms, ads for hippy communes, poems and inspirational quotes.

Davidson says these entries reflect the idealism of the era.

"It felt like there was a lot of hope among a segment of young people coming out of college," she says. "There was less of a feeling of doom."

Davidson says young people didn’t face the economic pressures they do now. Rent was cheap and jobs were plentiful. Young activists could afford to be idealistic. They saw radical possibilities in communal living and homemade yogurt.

"A lot of people thought that there was a sharp division between what you might call countercultural hippies and hardcore political activists," Casalino says. "And we didn’t believe that. We thought that both were needed."

The group saw activism as one way to change the world. But they also believed it was important to create alternatives to existing systems — to actually try to build the utopia they imagined.

"At the time, we really believed that we were creating a new world," Casalino says.

The People’s Yellow Pages was felled by a more prosaic consideration: money. Davidson says the project ended when the Friends Service Committee stopped funding it in the late '70s. By then, both co-founders had moved on to pursue new job opportunities. Casalino eventually became a doctor.

The People's Yellow Pages remains one of his proudest achievements — even though some of its entries make him cringe. "We were naive," he says. "But I think it's a beautiful thing. And I would still stand behind much of what we had to say in the book and much of what the book was intended to do."

You can see more entries from the People's Yellow Pages here.

This segment aired on June 28, 2021.