Advertisement

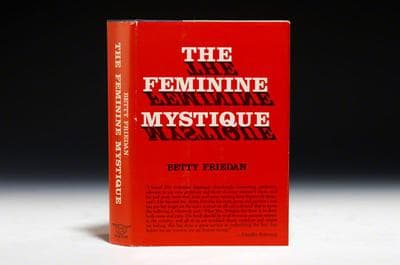

'Feminine Mystique' At 50: If Betty Friedan Could See Us Now

The 50th anniversary of Betty Friedan’s groundbreaking book, “The Feminine Mystique,” is being heralded in talks, panels and speeches across the nation. But while the milestone is noteworthy, it’s wise to remember where we came from and how far we have to go.

In tracing back some of my earliest memories of women’s liberation; I recall another 50 year anniversary.

In 1970, Friedan, then the president of the National Organization for Women (NOW), called for a march to celebrate the 50th anniversary of women’s suffrage.

Friedan asked New York Mayor John Lindsay to close Fifth Avenue for the event, but he refused. An estimated 20,000 women marched anyway.

Friedan’s tome didn’t start the women’s movement — but along with Simone de Beauvoir’s classic, “The Second Sex,” it helped to inspire women.

On the day of the march, I was in Boston, part of a group of women who stormed the infamous men’s-only dining room at Locke Ober, and demanded to be served.

Many were stunned by the women’s revolt. Men, in particular.

I remember watching ABC News anchor Howard K. Smith desert his objectivity on the air when he quoted Vice President Spiro T. Agnew: “Three things have been difficult to tame: the ocean, fools, and women. We soon may be able to tame the ocean, but fools and women will take a little longer.”

West Virginia Senator Jennings Randolph came up with his own derogatory phrase, calling the marchers “braless bubbleheads.”

It was as if an army of ducks had suddenly attacked and started making demands. Women weren’t supposed to be aggressive. They were supposed to be at home making dinner and ironing the clothes. I saw an echo of this attitude when Hillary Clinton ran for president, and young men held up signs saying “Iron my shirt!”

Advertisement

Women were asking to be taken seriously, and too often, men chuckled — albeit nervously.

At a recent Boston University panel on the impact of Friedan’s book, BU’s Dean of Arts and Sciences, Virginia Sapiro, remembered one of those “Click!” moments many women experienced at the time.

A politically active college student in the 1970s, she recalled a rally at which speaker after speaker stood and demanded an end to current evils — American imperialism, foreign wars, poverty, racism, etc. Loud cheers greeted each speaker. But when a woman stood to add “sexism” to the list, there were few, if any cheers. In fact, some of the men started laughing. Sapiro remembers feeling — suddenly — that she did not belong in a place where moments before, she had felt quite at home. She went on to become a distinguished scholar in the fields of political behavior, public opinion — and gender politics.

Many young feminists in the 1960s and 1970s emerged from the civil rights and anti-war movements. They expected that the young men they marched beside would join them in this new human rights quest. Many indeed did, including my late husband, Boston Globe columnist Alan Lupo, who always had my back. But many others did not.

If Betty Friedan were here today, I think she would be thrilled to see all the progress we’ve made — but similarly discouraged by how much more there is to overcome.

They were losing their valets, their maids, their cooks and their muses. They might even have to take care of the kids! But as women streamed into the labor force, men were among the primary beneficiaries of feminism. Today, it’s women’s wages that help to keep their families in the middle class.

Some on the left criticized Friedan and NOW because it attracted so many upwardly mobile white women. But Friedan had a gut instinct that if feminism could not enlist the ambitious middle class and was seen as just another anti-poverty program, it would fail.

Lacking Europe’s deep socialist traditions, the U.S. tends to view poverty as a personal and moral failing rather than as a structural problem. That idea surfaced again in the 2012 presidential race, when Mitt Romney made his now infamous 47 percent remark.

Over the long haul, the women’s movement has benefitted all classes of women. Roe v. Wade legalized abortion, making it safer and more accessible. Laws now define marital rape as a crime and prohibit overt discrimination against women in the workplace. Title IX gave women and girls equal rights in education and sports.

If Betty Friedan, who died in 2006, were alive today, she would be gratified to see three women sitting on the Supreme Court. She would be proud that a woman has commanded the space shuttle, and that combat roles are now open to women.

But I think she would be dismayed by a recent piece by historian Stephanie Coontz in the New York Times, “Why Gender Equity Stalled.” Friedan would have expected more progress.

She’d probably have a few choice words on hearing the title of the forthcoming book that I am writing with Dr. Rosalind Barnett, “The New Soft War on Women.” It looks at research showing how gender stereotypes hold women back, big time. She’d be sorry to see how much of that is still going on, after 50 years. She’d be upset at the prospect of a war on women, even though it is more subtle than in the past.

A famous cigarette ad from the 1970s, aimed at women, proclaimed, “You’ve come a long way, baby.” Maybe.

But Betty Friedan, an activist at heart, was not one to rest on her laurels. She’d scoff, “Nowhere near near as far as we should have!”

This program aired on February 20, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.