Advertisement

How Can A Lawyer Represent You Without Speaking Up?

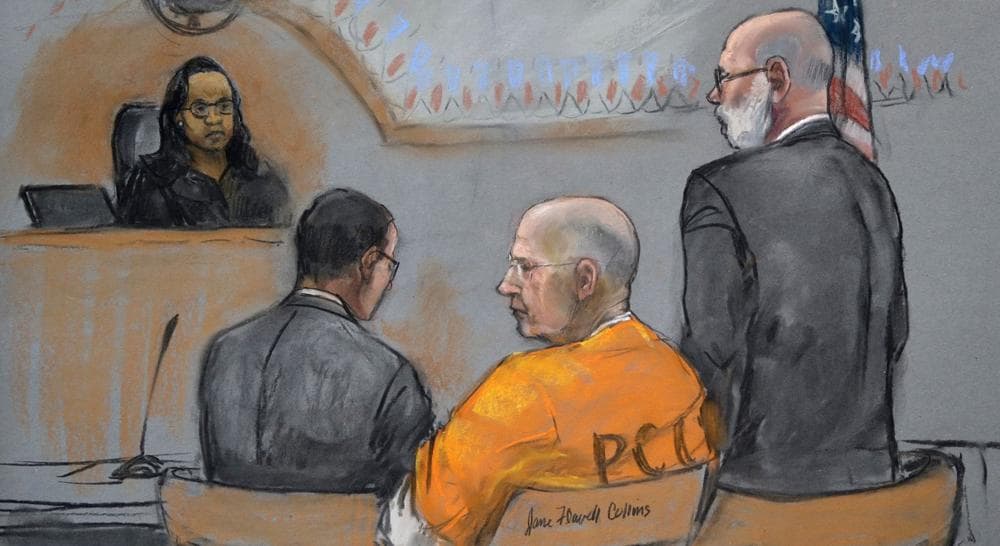

In the trial of James “Whitey” Bulger, the government moved to have the defense counsel comply with the ethical rules concerning comments to the media. The judge granted the request with one caveat: The rule applies to both prosecutor and defense counsel alike; both were admonished to follow it.

Local Rule 83.2A, which is 20-years-old, bars public comment by lawyers about a criminal case if there is a reasonable likelihood that commenting would “interfere with a fair trial or otherwise prejudice the due administration of justice.” Significantly, it does allow lawyers to “quote from or refer without comment to public records of the court in the case” during the course of the trial.

At first glance, the judge’s order sounds entirely appropriate. The outcome of criminal trials should be decided by impartial jurors, hearing only the evidence introduced in the courtroom, tested by the formal rules. Cases should not be tried in the press, on the internet, on television, in “Tweets,” in charges and countercharges without limits or rules.

The people who know the most — the lawyers — can say the least. What’s wrong with this picture?

But there are serious problems with the application of this rule. By the time of the trial, the government doesn’t have to say much about the case, while the defendant does. The government has already filled the airwaves with their version of the charges — comments that may well be entirely lawful and consistent with their ethical obligations.

Consider the following: When a crime takes place, the government releases information and appeals to the public to help apprehend the perpetrator(s). When leads develop, the government may well release this information to assure the public that they are doing their job. And “government” includes both the prosecutors, who are subject to the obligations of the ethical rules applicable to lawyers, and the police, who are not. The police speak about the case for entirely legitimate reasons. They too want to keep the public apprised of the conduct of the investigation from day one.

When there is an arrest, there is usually a self-congratulatory press conference. We have all seen them. The drug arrest with the pile of contraband on the table reported — without irony — that “this was the biggest seizure in the history of Boston” or “Massachusetts” or “New England!” The defendant is videotaped as he is led, handcuffed, into a police station or as he lamely tries to cover his face en route to court.

Advertisement

In this era of 24/7 coverage, the victims — if there are victims — also have a role to play. They will invariably appear on camera, the video loop recounting their pain over and over again.

Rarely is the “other side” portrayed, apart from the account of police, prosecutors and victims: The news is exclusively about the crime, then the investigation, then the suspect and then the arrest. Few defendants — except the wealthy ones — have lawyers at the ready to answer as the investigation begins to crystallize around them.

By the time defendants are finally represented, when there is a formal indictment or complaint, the damage is done. If they are not well known prior to the crime — a politician for example — the public knows about them only through what the police, prosecutors, and victims have already said and said over and over again. Their portrait is already drawn to the public and it is hardly favorable.

That’s the rub. Coming in at the last stage, the formal trial, defense counsel are not supposed to say much, even though they should. Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of the law school at the University of California, Irvine, argues that “a lawyer who is zealously representing a client, at times, should be making statements to the media.”

The government lawyers are similarly bound by the rules, but for them, it hardly matters. They can rise above the fray, announcing, as the prosecution did in the Bulger case: “Defense! You must follow that ethical rule carefully; no press conferences at the courthouse door.”

After all, their version of the facts has already been splayed across the airwaves — admissible and inadmissible evidence, real and unsubstantiated accusations. And rule 83.2A only bars the statements of the lawyers, not the victims whose reactions to the trial can be shown on television every night. The only party that needs to speak, is not supposed to.

For more than 40 years, committees of lawyers and judges have worked to develop sensible modern guidelines for lawyers’ interactions with the media, struggling to balance the right to a fair trial with the right of free expression.

By the time defendants are finally represented, when there is a formal indictment or complaint, the damage is done.

In a 1991 concurring opinion (joined in by four justices) on the constitutional limits of lawyer speech restrictions, Justice Anthony Kennedy argued: “An attorney’s duties do not begin inside the courtroom door. He or she cannot ignore the practical implications of a legal proceeding for the client ... An attorney may take reasonable steps to defend a client’s reputation and reduce the adverse consequences of indictment, especially in the face of a prosecution deemed unjust or commenced with improper motives.”

Indeed, Justice Kennedy even suggested that there was no convincing case for restrictions on the speech of defense attorneys at all, apart from the requirement that they speak only about admissible evidence.

One could argue that the media comment doesn't make a difference, that all that matters is what the jurors think, and they are directed to focus only on what is going on in the courtroom. If we believe that the jurors are not listening to the media hype — and after 17 years on the bench, I do — then public comment, within reason, after the jury is selected should make no difference. If we do not, if we believe that — notwithstanding the court’s best efforts and the jury’s good faith — information trickles down, then no one should be able to speak.

Since we can’t do the latter consistent with the First Amendment, we should be flexible about the former, allowing the lawyers to speak. This is especially the case given the federal court’s insistence that there can be no cameras in criminal trials. Without cameras, the proceedings in the Bulger case, or any other case, have to be filtered through reporters hastily writing what they thought they heard or “Tweeting” their perceptions of what is going on. The people who know the most — the lawyers — can say the least. What’s wrong with this picture?

Related:

This program aired on July 22, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.