Advertisement

Our Struggle: The Story Of An Unusual — And Deeply Unsettling — Family Heirloom

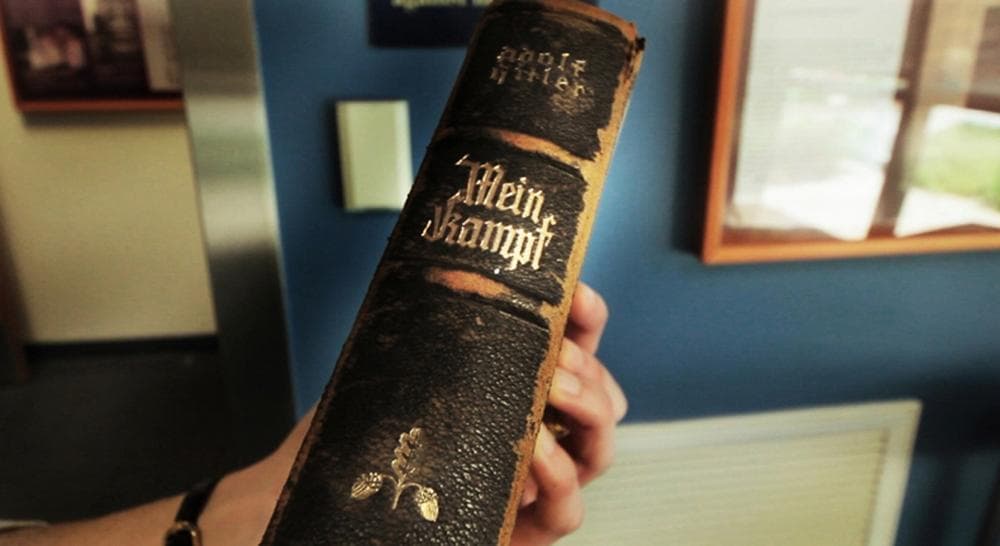

Most people are not repulsed by their family heirlooms. But then again most family heirlooms don’t include a 1937 edition of “Mein Kampf.”

I grew up with the story that my great uncle Eddie Cohen, from Brooklyn, N.Y., killed a German soldier in battle during World War II and found a copy of "Mein Kampf" in his enemy’s rucksack. He pilfered the book from his victim and eventually brought it back with him to New York.

After spending almost four years researching the origins of this copy of Mein Kampf, I’ve learned that war stories can have second and third iterations as they are passed down through subsequent generations. And long after the veteran has died (the lone person who can set the record straight), the artifact at the heart of such tales remains intact, prompting the curious among us to investigate the story behind the object.

Yet the process is not clean-cut.

Most people are not repulsed by their family heirlooms. But then again most family heirlooms don’t include a 1937 edition of 'Mein Kampf.'

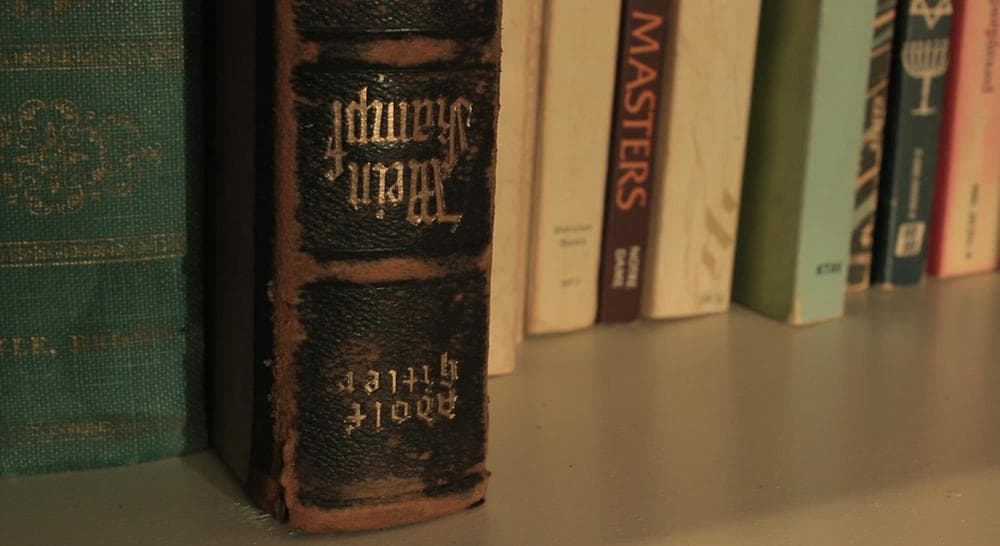

What we do know is that Eddie gave the war souvenir to his sister, my Grandma Helen, who lived on Long Island. Helen’s son (my dad) became its next owner in the 1960s. He later displayed it upside down on the bookshelf in his study throughout my childhood in Brookline and Newton.

If you ask my father now, he’ll say that Uncle Eddie didn’t actually kill the German soldier. He merely stumbled across the "Mein Kampf," which was lying next to the body of an already-dead German soldier.

If you ask my mother she’ll say Eddie tucked the book inside his uniform, to protect him from flying bullets — an ironic twist that the anti-Semitic text that laid the groundwork for the Nazi party would be responsible for saving a Jew in battle.

My brother would side with my version of the story.

And if you ask my sister, she’ll say, “I never heard that story growing up. I didn’t even know dad had a copy of ‘Mein Kampf’ until you started doing research on it.”

It’s like a family-lore version of “telephone.”

But we are all united in agreement that the thought of physically touching the book gives us the heebie-jeebies. The book, quite literally, creeps us out, even though it’s been nearly 70 years since the end of World War II, and none of us were present in Europe during the years of fiery catastrophe. Along with the book, we inherited the very Jewish burden of second-degree, post-Holocaust trauma, a dizzying concoction of grief, guilt, ethnic sensitivity and fear. The book itself is a reminder that artifacts of war are not limited to physical objects, but can also include the feelings they invoke, which, like a physical object, is part of our inheritance too.

Using war heirlooms to test family history is tricky business. The story of Eddie’s battlefield heroism did not mesh with the evidence that emerged through recent oral histories and archival research. So we’re left with variations of a dramatic story we can never verify and a faded copy of Hitler’s political manifesto whose existence we can’t deny.

I’ve often joked with my husband, who recently completed a documentary film about this investigation, that the whole project would have been moot if my great uncle was still alive. The mystery of where and how he got the book could have been solved with a five-minute phone call.

I imagine Eddie chiding me for being too dramatic: “Hindaleh, why would I take the time to go through this soldier’s sack with bullets flying overhead? You think I wanted to be weighed down in battle with a clunky Mein Kampf? That’s a furshlugginer story. Actually I picked it up at a used bookstore along the Champs Elysees while on leave in Paris. Hate to break it to you.”

And I’d say, “Oh thanks, Uncle, for clearing up the confusion.” And this hypothetical conversation would have saved me years of research.

Yet the certainty he could have offered is unattainable. I became captivated by this Mein Kampf — and its physical and metaphorical place in a Jewish household — nearly a decade after Uncle Eddie died. We never spoke about the book.

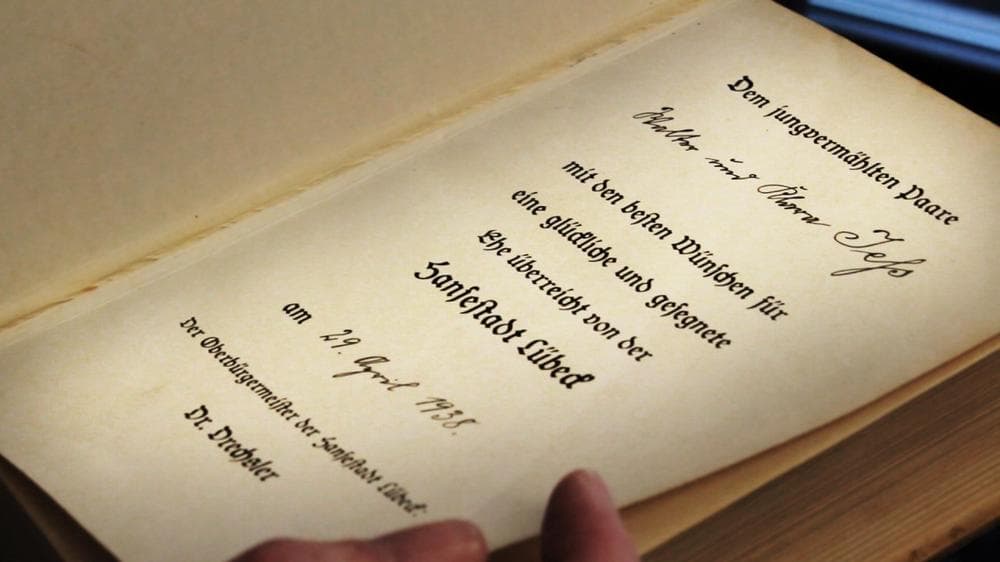

If Eddie were still alive I would have told him what I learned about the Mein Kampf’s original owners. Walter Jess was a bureaucrat. His wife, Klara, was a nurse before she married her husband. She enjoyed playing piano. They had three children. If Eddie knew German he could have read the inscription on the inside cover of the book, a wedding present to the Jess couple from their mayor in 1938.

I also would have told Eddie that I’m stuck contemplating the ways happenstance can be impactful. My only child, born this past June, shares the same birthday as Walter Jess. There’s only a .2 percent chance of that happening. But it did. And now the uncomfortable connection between our two families is reinforced. Not through an act of war but through the birth of a baby.

My family is moving toward peace. Thanks to a copy of “Mein Kampf,” brought home by a soldier, and the synchronicity that seems to follow it.