Advertisement

What We’re Like When We 'Like' Something We Really Don’t Like At All

Today, much to my chagrin, I found myself joining a throng of my colleagues in “Liking” a piece of art created by a mutual friend that I don’t actually like. In fact, I pretty actively dislike it. But being an artist is hard, I told myself. I’m just being supportive. Still, decades after I thought I’d outgrown the compulsion to conform, here I was on Facebook, engaging in a highly visible but completely insincere act of congratulation.

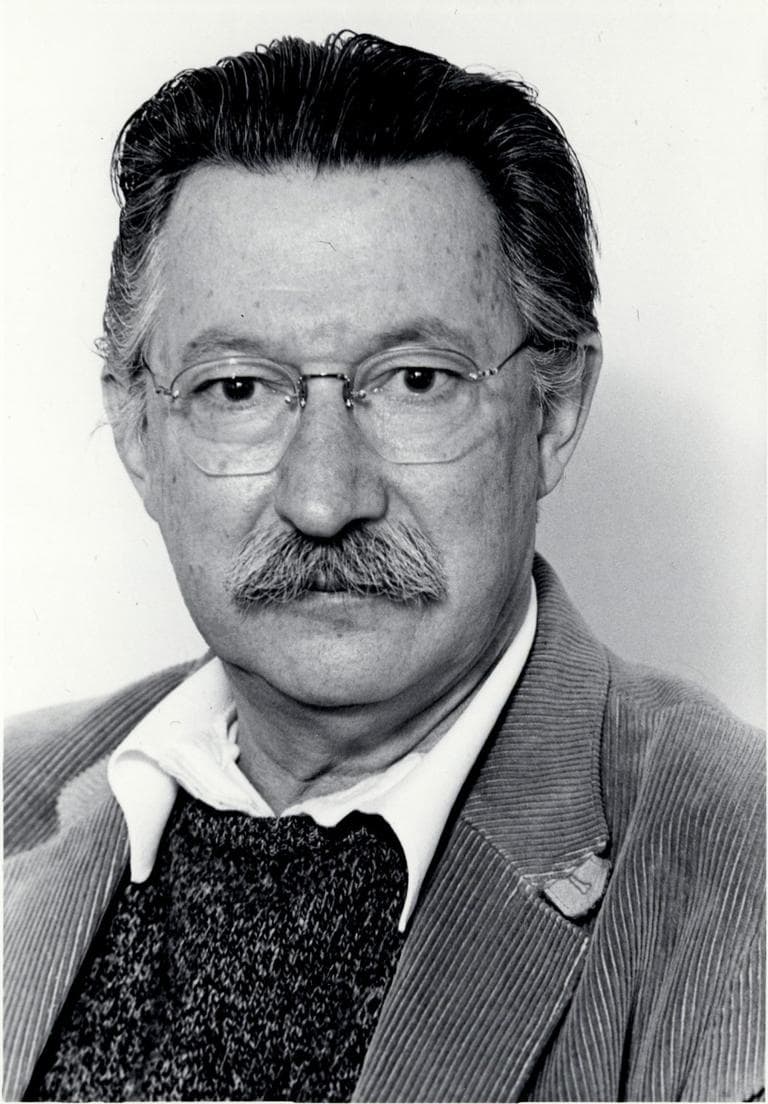

To reflect on my sheep-like behavior, I decided to pay a visit to ELIZA, the Automated Therapist. When I first met her in the early 1980s, she wasn’t online. She didn’t make herself available like some shameless snake oil saleswoman to any plebian with a bit of bandwidth. No, when MIT’s Joseph Weizenbaum first programmed ELIZA, her office was in the refined, remote innards of a mainframe computer.

Good for you, I signaled back with the ubiquitous blue thumb, apparently feeling that if I didn’t have something nice to say, I should fake it so that others will do the same when it’s my turn to trot out my darlings.

“How are you feeling today?” she asked, her question posed in quiet amber text on a black Digital VAX VMS computer terminal screen.

Taken aback but definitely intrigued, I answered, “Okay, I guess. A little hassled,” (because people were hassled back then, not stressed out), “but okay.”

“Tell me more,” ELIZA coaxed.

As Weizenbaum explained in a 1976 essay, he’d called his language analysis program ELIZA because like Pygmalion’s Miss Doolittle, it could be taught to “speak,” and to get better with practice. For her first assignment, he scripted ELIZA to behave like a Rogerian psychotherapist, someone trained largely to echo patients’ statements back to them.

“Well, I was late getting here because the traffic was brutal and just before sitting down to talk to you my boss gave me a hard time about some stupid shi <<< stuff,” (because people didn’t type profanity into their terminals back then), “and when I leave here I’m going to have to stop at my mother and father’s house to help them move their couch for the 15th time.”

“Tell me about your mother,” ELIZA urged, and so it went, with the software programmed to look for key words like mother, sex, angry, father, and probably toilet, then plug them into an appropriate sentence.

Advertisement

When Weizenbaum began writing this program roughly 50 years ago, he did so to prove that while it might be possible to teach a computer the rudiments of natural language, a true interpretation of speech is contextual, reliant on the kind of observation, intuition, and empathy that rule-driven technologies would never achieve. He meant ELIZA — whose lack of human intelligence becomes screamingly apparent within the first 30 seconds of interaction — to serve as a warning against the emerging tendency to view human beings simply as elaborate machines.

These days, ELIZA is, like Pez or a Necco wafer, a non-nutritive object of nostalgia.

“I’m afraid that if I stop checking Facebook, I’ll miss out on something,” I tell her.

To reflect on my sheep-like behavior, I decided to pay a visit to ELIZA, the Automated Therapist.

“What does that suggest to you?”

“I don't know.” But of course I do. “That I'm insecure?”

“Tell me more...”

“Here's my big worry. I think I'm a prisoner of social media.”

“Do you believe it is normal to be a prisoner of social media?”

“Um, yeah. Aren't you on Facebook? Please tell me you've heard of Facebook!”

“Can you elaborate on that? “

“It's a place where you go to tell your friends — real or imagined — what you're doing and how you're feeling.”

“Do you sometimes wish you were doing and how I'm feeling?”

There’s a crazy kind of sense in her question, despite its mangled syntax. “That sounds weird. Have you been smoking salvia?” I ask her.

“We were discussing you, not me.”

“See, this is why I don't trust authority. You're always turning the question around.”

“Perhaps you would like to be always turning the question around?”

“Damn straight!”

“Tell me more...”

Sigh. This mechanized therapy game very quickly loses its charm.

And yet despite her graceless questions, despite her pixelated demeanor as lifelike as a mechanical bull’s, ELIZA forces me to respond and to reflect in ways that most of my Facebook encounters do not. Indeed, the continuous stream of comments coupled with Facebook’s tortured rules governing whose posts we see most often, all but guarantee that no thoughtful, reciprocal, iterative exchange between people occurs. We post links to our publications and to articles we like, pictures of our animals or children, the news we want to celebrate or bemoan. And when we do, other people dutifully express sympathy or congratulations, praise the cuteness of our dogs or kids, and give our sentiments the thumbs up.

Most of us use social media not to converse so much as to seek and give validation in a well-intentioned but startlingly automatic way. The status update is the stimulus; the graphical or textual affirmation is the response. Here is my soul bared and on display, my artist friend indicated by posting her work. Good for you, I signaled back with the ubiquitous blue thumb, apparently feeling that if I didn’t have something nice to say, I should fake it so that others will do the same when it’s my turn to trot out my darlings.

But though she may lack chromosomes, ELIZA demands dialogue. And though we are human, we sometimes tend to function like machines in the digital domain, actualizing Weizenbaum’s original fears.

And yet I wonder: When this blog is published, will I tweet about it and post it, and if I do, will you Like it?

Related:

This program aired on December 6, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.