Advertisement

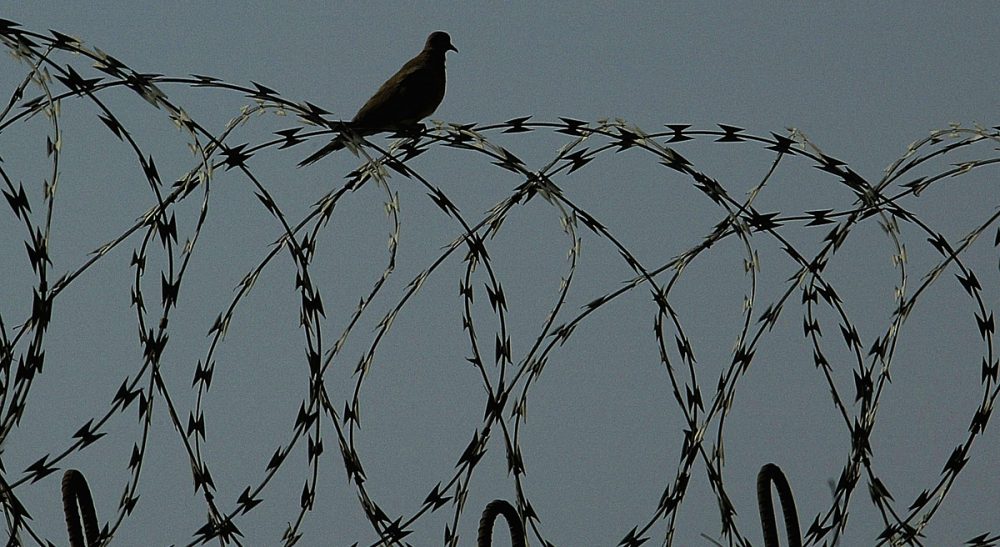

When It Comes To Human Rights, Media Exposure Is A Double Edged Sword

Media exposure is an element of public life that is considered essential to a constitutional democracy that protects human rights.

Exposure helped make 2013 a turning point in the history of gay rights, a year during which the Supreme Court deemed the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) to be unconstitutional and the number of states legalizing same-sex marriage doubled from 9 to 18. Scholars have attributed part of the rapid shift in public attitudes towards same-sex marriage over the past decade to the frequent portrayal in news and popular media of the lives of real and fictional gay couples (such as Cam and Mitch in "Modern Family").

But one year ago, the controversy over the use of torture as a tool of counterterrorism was also re-ignited in response to the box-office success and Oscar nominations of the movie "Zero Dark Thirty." Commentators have argued that the regular depiction of torture in popular movies and television shows like "Zero Dark Thirty" and "24" has contributed to the increasing acceptance of its use in recent polls among the American public.

Might media exposure be a double-edged sword when it comes to shaping attitudes in the cause of human rights? A new hypothesis linking two large bodies of research in social psychology suggests that in some cases, it may also lead us to favor morally objectionable practices such as torture over time.

The first body of research has demonstrated a mere exposure, or familiarity, effect. The idea is simple: experiencing something repeatedly — whether it involves viewing a painting, hearing a song, or encountering a person -- generally makes you like that object or person more over time. Researchers have also found this effect with neutral stimuli such as meaningless patterns and tones and in naturalistic settings such as schools and the workplace.

if you simply see something depicted often enough in the news or the movies, what was once reprehensible may start to feel safer to imagine, debate, and even justify.

In one famous example, researchers assigned different individuals to quietly sit in on classes in a large lecture hall at different frequencies throughout a semester — those individuals who attended more often were rated as more attractive by the other students in the class at the end of the term. One explanation for this effect connects exposure to safety: we like what is familiar because all other things being equal, it’s likely to be something safe and approachable in our environment.

A parallel line of studies has found that emotions such as disgust and empathy play a key role in people’s moral judgments. For example, research shows that participants who are generally more prone to feel disgust or who are unconsciously induced to experience physical disgust in laboratory experiments (such as from a bad smell in the room) express harsher moral attitudes, including towards gay marriage and gay men. Moreover, these emotions account for people’s moral judgments better than any rational arguments they might offer to explain their views.

Together, these findings support an intriguing psychological hypothesis: that mere exposure to something not only promotes liking or positive emotion, but also moral acceptability. On one hand, this may mean that regular media exposure helped some to overcome prejudice and support the cause of same-sex marriage. On the other, it may have dimmed the horror others initially felt towards torture in the wake of the 9/11 attacks.

mere exposure to something not only promotes liking or positive emotion, but also <i>moral</i> acceptability.

Thus far, the evidence for this “moral mere exposure” hypothesis is only preliminary: a study I conducted with two colleagues showed a link between liking and moral attitudes towards more neutral everyday objects such as consumer products. And to be sure, there are multiple other political, demographic, and psychological forces at work in changing norms about same-sex marriage and torture. For instance, there are still significant gaps between liberals and conservatives in polls on these issues and differences in their relative levels of exposure are unlikely to provide a complete explanation for the ideological divide.

But these converging lines of social psychological research suggest that media exposure may not be an absolute good in a healthy democracy: if you simply see something depicted often enough in the news or the movies, what was once reprehensible may start to feel safer to imagine, debate, and even justify.

Related: