Advertisement

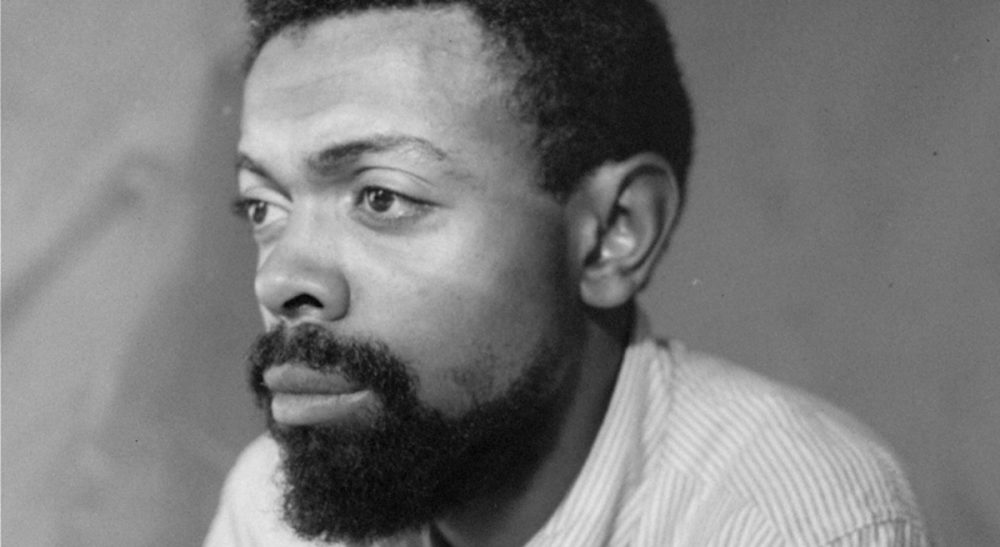

Amiri Baraka's Legacy As An Urban Ethnographer

On January 9, 2014, we lost activist and writer Amiri Baraka. In many of their remembrances of Baraka’s life, cultural critics, scholars, and fellow poets have celebrated Baraka as a revolutionary writer, radical activist, and innovative jazz critic. However, I want us to remember another aspect of Baraka’s legacy. He was also an urban ethnographer.

Baraka helps vividly describe and document the black-centered world of Greenwich Village in the 1960s. His first-hand accounts of racial, sexual, and cultural politics in the Village are groundbreaking. He challenges the myth of Greenwich Village interracialism, which frames that space as a harmonious liberal cultural enclave. Baraka offers a lens through which we can discuss police brutality and de facto segregation in a liberal, northern space. He unpacks the politics of interracial relationships and how certain areas of the Village were more or less hostile to these couples.

His first-hand accounts of racial, sexual, and cultural politics in the Village are groundbreaking.

He also writes extensively about the nexus of well-known and obscure black poets, artists, and musicians who lived in and/or performed in that area, at that time: Ted Joans, Calvin Herndon, Lorraine Hansberry, Gloria Tropp, and Bob Thompson. Baraka takes us on a journey down the Village’s winding streets, as he recites the names and locations of popular dives and restaurants that black folks frequented.

Typically, white Beat Generation writers such as Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsburg, and Joyce Johnson serve as our guides through Village life and culture. In their writings, black voices are marginal and merely serve as colorful backdrops that give the space what Kerouac calls its “subterranean” energy. While Kerouac may have appreciated the subterranean vibe of black jazz musicians, poor people, and drug addicts, black cultural politics were not central to his work.

When we put Baraka, the urban ethnographer, in conversation with his black contemporaries who have also written about their experiences in Greenwich Village in the early 1960s, such as writers James Baldwin and Audre Lorde and singers Nina Simone and Miriam Makeba, we learn so much about black queer identity politics, black internationalism, and the roots of the soul aesthetic of the music and fashion that we typically associate with the Black Power movement of the 1970s.

We can also use their collective writings to map the well-trodden terrain between the Village and Harlem, tracing how black intellectuals, musicians, and poets moved back and forth between these two cultural epicenters. The intellectual payoff is huge because their work advances our understanding of the insidious nature of Jim Crow segregation (even in the North) as it lingered on well after the Brown vs. Board of Education decision in 1954. We also learn more about the translocal race, class, and gender politics of New York City by comparing and contrasting the black experience in Greenwich Village and Harlem.

While Baraka may not have been formally trained as an ethnographer, the work he has produced in this regard is an aspect of his legacy that we must honor. We need black voices as ethnographers who can give us first-hand accounts of what it was like to move through urban spaces on a daily basis.

On Saturday, Amiri Baraka will be laid to rest following his funeral at Newark Symphony Hall in Newark, New Jersey. Long after his funeral, educators around the world will teach his works to their students. I know in my classes, we will focus on Baraka the ethnographer and what he teaches us about race, class, gender, sexuality, violence, and culture in post-WWII era America.

Related:

- Listen to Baraka's conversation with Fresh Air's Terry Gross in 1986

- Amiri Baraka's Legacy Both Controversial And Achingly Beautiful