Advertisement

Resisting The Siren Call Of Academic Isolationism

“Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.” — Nelson Mandela

Small choice by small choice, countries which view themselves as moral leaders are disengaging from a troubled world, leaving those struggling to create positive change within their communities with ever fewer international partners on which to rely.

Now the disturbing trend toward global disengagement is bubbling up in American academia. Initially, we heard concerns voiced among some influential Liberal Arts faculties regarding limits on the exercise of academic freedom in a spate of far-flung academic outposts. Most recently, the movement has blurred into a desire to use formal academic boycotts and intellectual isolation as a punitive tool for expressing social and political disapprobation.

I believe strongly that positive engagement is a much more powerful weapon than washing one’s hands of the world’s moral complexity.

It is important to differentiate between the arguments from some U.S. faculties who favor intellectual disengagement with the autocratic, theocratic, or post-conflict world. Their most compelling concerns are rooted in the cherished tradition of academic freedom. Academic freedom is required to create a “safe zone” for the expression of controversial ideas — making universities havens for vigorous intellectual debate outside the constricting context of political, scientific and religious mores.

The notion of boycotting academic cooperation or refusing to teach in a given country due to political, ethical or moral objections to that country’s politics is another matter entirely. The argument urging disengagement follows two distinct lines. Some are urging universities to become political actors by supporting an academic boycott of a nation, to use the bludgeon of public opinion and the carrot of access to knowledge as a force for social change. The second line of argument supporting academic isolationism is that it is more morally defensible to abstain from contact with academic institutions and students stranded in “rogue” states than to engage. This argument goes to the core question about the value of academic engagement.

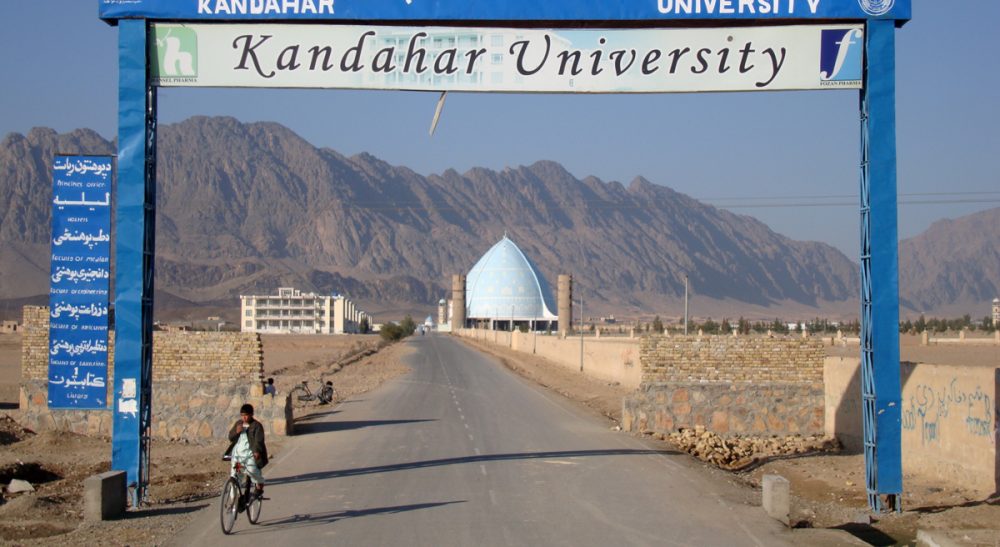

My own experience bringing access to higher education to places where freedom of thought is legally and culturally treacherous, and even sometimes lethal, began in Afghanistan. As a trustee of the American University of Afghanistan (AUAF) and as the co-founder of a non-profit that brings Afghan lawyers and judges to the U.S. to attend law school, I saw how astonishingly the thirst for knowledge survives, in fact thrives, even in the most oppressive circumstances. Many students who came to AUAF had risked death to study English at the height of Taliban oppression; others recounted how their families had taken refuge in Pakistan or Iran in order for their daughters to receive an education.

Most students at AUAF take significant physical risk and endure cultural disapproval for daring to attend a Western-style, mixed-gender university and to study with American professors in Kabul. As the deadly attack in Kabul earlier this month so tragically reminds us, these risks extend to the committed faculty and staff who work to fulfill the university’s mission. Nonetheless, the best hope for a positive outcome in Afghanistan lies in the love of knowledge I have seen in these Afghan youth. In 10 years’ time, these young leaders will be our primary legacy in Afghanistan and we will likely wish we had invested more in schools and less in weaponry. The power of knowledge to mold future generations, to create real social change, is profound and infinitely more lasting than any transitory military dominance. But, however brave the students may be, they cannot educate themselves. They must have international academic partners with the courage and tenacity necessary to share those real risks and to invest in their future.

I believe strongly that positive engagement is a much more powerful weapon than washing one’s hands of the world’s moral complexity. At Babson, we partner with dozens of academic institutions around the world in countries like Thailand, China, Malaysia, Colombia, Saudi Arabia and Russia. We, too, wrestle with the issue of how best to engage. In each case, we take great care to consider the ethical and reputational impact on the College as a result of our work in countries with significantly different cultural norms and political environments than our own. However, as a college dedicated to putting the power of entrepreneurship into the hands of as many people as we can, we choose engagement.

The power of knowledge to mold future generations, to create real social change, is profound and infinitely more lasting than any transitory military dominance.

We agree with the assessment from Jim Clifton of Gallup that, "If countries fail at creating jobs, their societies will fall apart.” In his book, “The Coming Jobs War,” Clifton emphasizes the need for more job creators; those who can drive greater economic opportunity and, ultimately, more hope around the world. Babson believes entrepreneurship is the world’s greatest force for creating economic and social good, a sentiment echoed by Secretary of State John Kerry as he seeks to constructively engage with emerging economies on behalf of the Obama Administration.

As academics, we must trust that more — not less — knowledge, in more — not fewer --hands, will result in greater global good: the economic and social empowerment of women, the broader embrace of human rights and the lifting up of people from poverty through the power of education.

Members of the academic community have the right to choose for themselves where and how to share the knowledge they possess, but I hope most choose to share it widely and without caveats. There are very few countries which could clear the tough moral, political and ethical hurdles proposed by proponents of academic isolationism, but plenty of young people everywhere who deserve a better future than their countries currently provide. We, as educators, must have the courage to be willing partners for young people everywhere who share curiosity and an open mind.