Advertisement

The Kid Is Alright

It’s July. Swimming season. The season of vulnerability.

Summer reminds of a time when I developed a strange and obsessive relationship with something close to me. Not a friend. Not a girl. A body part.

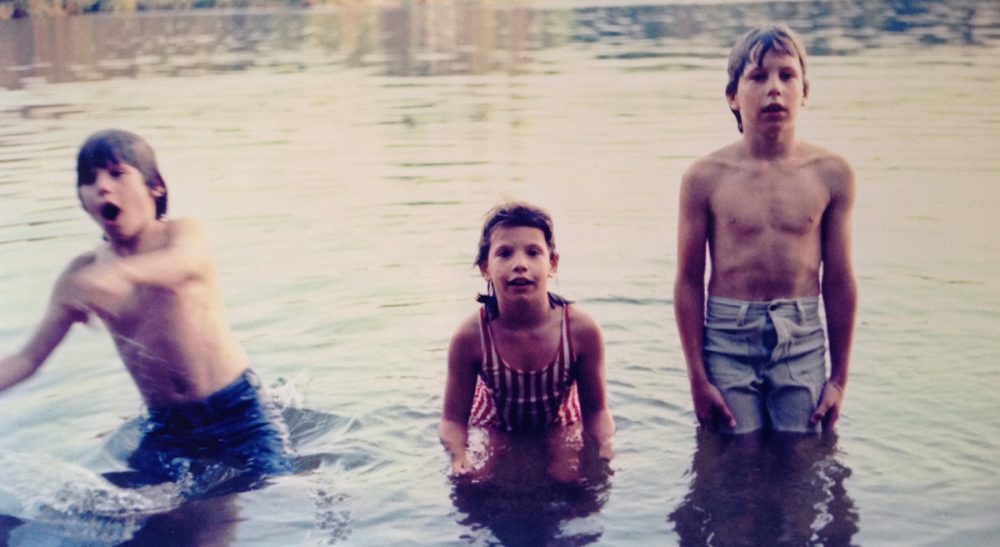

Picture me swimming along the sliver of public beach of the pond in my small New Hampshire town. It’s 1976 or 1977. I’m standing in the water, watchful of the leeches that lurk close to shore. But I’m also watchful of prying eyes, of glimpses and ganders and guffaws.

Because, as an eight or nine year old, I am convinced that every kid on the beach, along with all their moms and dads, are all staring at my belly button.

My outie belly button. Bulbous. Grotesque. How did I become so weird? So different? So pathetic?

I hike my cut-offs above that monstrosity. When I exit the water, I move my hands, casually, to cover the center of my belly. On dry land, I quickly throw a towel around me and shiver on the beach.

My siblings, who leap and swim near the shore, are oblivious to my internal torment. They have normal belly buttons. Meanwhile, I wade out deeper, where the waterline covers my waist. I hike my cut-offs above that monstrosity. When I exit the water, I move my hands, casually, to cover the center of my belly. On dry land, I quickly throw a towel around me and shiver on the beach.

“Hey kiddo,” my mom says. She can tell something is up. “You O.K.?”

“Sure.” I tug a striped Bobby Brady T-shirt over my skinny body. I can finally relax. My aberration safely hidden under my shirt, I take a deep breath. Perhaps no one has seen me. Perhaps no one knows about my deformity after all — that tiny alien, that nose or a tail or tooth eager to burst through my innards and explode from my abdomen and devour me.

Outie. Outsider. Outcast.

I remember how painful that sense of “difference” felt. How I did not want to attract attention to myself. I even asked my mom if surgery was an option — so this quiet, insecure kid could feel better about his weirdness. My mother told me I could get an operation to turn my outie into an innie, but first I had to let some more time pass. Be patient, she told me. Lots of kids have them, she assured me. You won’t feel so different in a while.

She was right. About a year later, I had forgotten all about my outie. The belly button obsession was a phase I passed through, like a lot of phases that kids endure. Later on in life, I would come to obsess about other body issues. I was too short, or too scrawny, compared to other boys. My many moles and freckles made me a weirdo. My nose? Too big. Then came other hang-ups, such as what might happen while giving oral reports in History class. (Psst! Erections.)

Reflecting back on that little Ethan — a quiet, nerdy, silly kid — I see that I was preposterously self-obsessed to think that anyone was even looking at my belly button, let alone my nose or other body parts. But here’s what turned the tide. By naming my fixation and talking about it with my mother, even as a little kid, I had dispelled the power my outie wielded over me. By identifying my fear of being different, my complex retreated, the same way some outies do.

...my preoccupation with 'what was different about me' paradoxically taught me to feel more comfortable in my skin.

Growing up, I longed to fit in and be just like all the other boys. But over time, I came to see that something that could set me apart, my outie, might be something to cherish. By the time I left high school, normal felt boring. Docksiders, polo shirts, soccer team? Not for me.

In fact, I have always strived to be different, I just didn’t know it at the time. When I realized I wanted to be a non-conformist, to find an identity that was unique, that “out” aspect of my “outie” became a metaphorical embodiment of my outsider status. I embraced my inner dork. Dungeons & Dragons? Sure. Become an artist? Move to Paris? Why not? I learned how let fly my freak flag high and proud, emblazoned with all the kooky behaviors that defined who I was. I began to like the stuff that made me me.

I now see that my preoccupation with “what was different about me” paradoxically taught me to feel more comfortable in my skin.

Today, I don’t worry about my belly button, or whether I fit in. And I still have that outie. It suits me. My outie is like my mini-me.

At Walden Pond or the beach this summer, when I take off my shirt, and get ready to swim, I don't even think to think about my outie anymore. I simply walk down to the water's edge, take a breath, and jump in.

Related: