Advertisement

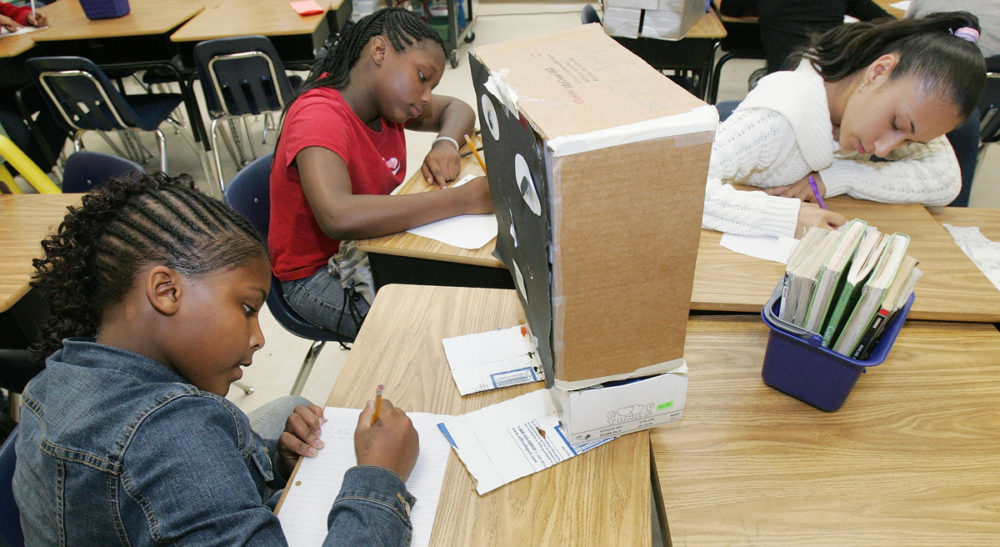

Where The Boys Aren't: The Power Of An All-Girls Education

A study recently released by MIT graduate student Jason Sheltzer and Twitter engineer Joan Smith highlights the tendencies of top male faculty in life sciences to hire fewer women than their female counterparts do. This is yet another example of the gender gap in the sciences. The study offers perspective on why women remain under-represented in leadership positions. After analyzing more than 2,000 laboratories from the top-ranked research institutions in the U.S., the study found that labs run by top male professors employed 35 percent female post-doctorals, compared to 46 percent in labs run by top women.

To right that imbalance, we must continue to prepare more women to assume leadership positions in the sciences (and math and engineering too, for that matter). I believe that for many women, the starting point is an all-girls education.

The challenge is not in the fact that we are wired differently -- neurobiology is not destiny. The challenge is in the fact that our culture amplifies these gender differences.

Brain research conducted in the past 20 years shows that girls’ and boys’ brains are programmed differently. The challenge is not in the fact that we are wired differently — neurobiology is not destiny. The challenge is in the fact that our culture amplifies these gender differences. As the psychologist JoAnn Deak points out in her book "Girls Will be Girls," “Every interaction a child has in the course of the day influences the adult the child will become.” Prenatal hormones might create toy preferences by gender (dolls for girls and trucks for boys), but educators and parents often reinforce what we view as appropriate. Instead, we should encourage girls to play with puzzles and blocks, and encourage boys to learn to sew or play with dolls.

A favorite personal example of mine comes from my son's experience in kindergarten at a K-8 coed school in New York City, when a letter came home to inform parents that the boys were dominating the blocks area in the classroom. To ensure that the girls had an opportunity to play with the blocks, the teacher had designated Fridays as the “official blocks day” for the girls. What message does it send that the girls get the blocks one day a week? I sent my daughters to an all-girls kindergarten where they could play with blocks any day of the week.

So, while the brains of boys and girls are different, our culture encourages those differences because of stereotypes about gender. In a single-sex school, girls can more easily spend additional time in areas that they may not be hardwired to choose.

In "How Girls Thrive" JoAnn Deak also examines how, in coed settings, boys receive more attention in the classroom than girls, are more talkative, call out answers more frequently and raise their hands more quickly than girls. For example, in a coeducational setting, girls are five times less likely to receive attention from teachers; three times less talkative in class; and half as likely to demand help or attention.

The fact that girls are more engaged in an all-girls setting than in a coed one demonstrates one benefit of a single-sex school, but other examples also make the case:

The presence of a mentor or role model can lead to increased self-esteem in girls and help them excel in areas that aren’t traditionally “female” subjects. In an all-girls environment, students’ role models include faculty, administrators and fellow classmates. Peer tutoring and education programs at single-sex schools create and enhance these relationships.

Advertisement

Self-esteem is critical to girls. A study by the American Association of University Women found that self-esteem has a more direct effect on behavior in girls than in boys, and that girls rate their self-esteem as lower than that of boys. If, therefore, a girl thinks she is not good at a subject, she won’t pursue an advanced course in that area. At an all-girls school, girls are the best math students and the best science students.

To teach girls to be leaders is to cultivate their skills in an atmosphere that lets them know they are in charge.

According UCLA research, 48 percent of girls school alumnae rate themselves as great at math, as opposed to only 37 percent of girls in coed schools. In addition, 36 percent of graduates of independent girls schools consider themselves to have strong computer skills (compared to 26 percent of their coed peers) and three times as many alumnae of single sex schools (versus coed schools) plan to become engineers.

In coed settings, girls tend to shy away from competitive behavior and risk-taking by early adolescence. However, research has also found that girls at single-sex schools are more likely to take a risk than girls in coed schools, in large part because the environment feels safe. As Leonard Sax points out in his book "Why Gender Matters," we know that if you explore new situations, face your fears and master them, then you will be able to face similar challenges in the future.

We talk about the gender gap and the need for more female STEM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics) professionals, but it’s not a problem with a simple solution. It’s a problem that needs to be addressed before it begins, and where that begins is as early as middle school or sooner. It isn’t about encouraging girls to try classes that are “different;” it’s about teaching our girls to think that those courses aren’t “different” to begin with, and instilling that mindset at an early age. To teach girls to be leaders is to cultivate their skills in an atmosphere that lets them know they are in charge. At a single-sex school, there is no such thing as “male dominance,” because there is no option for males to dominate. And if male students aren’t the ones dominating in the classroom, who are? Girls.

Related: