Advertisement

What Iraq's New Prime Minister Can Learn From Nelson Mandela

As Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki negotiates his exit from power, the one demand that the U.S., Iran and Iraq’s Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani can agree on is the need for the new leadership of Iraq to form an inclusive government of Shia, Sunni and Kurdish leaders.

After eight years as prime minister, Maliki is being forced out for the same fundamental reason that former Egyptian leader Mohammed Morsi is in jail: They both represented marginalized communities and rose to power in the wake of brutal dictatorships. Both failed for the same fundamental reason: They could not bring themselves to be inclusive.

...building an inclusive government is the most common characteristic of a successful political leader in a divided society, while exclusion is the main driver of conflict.

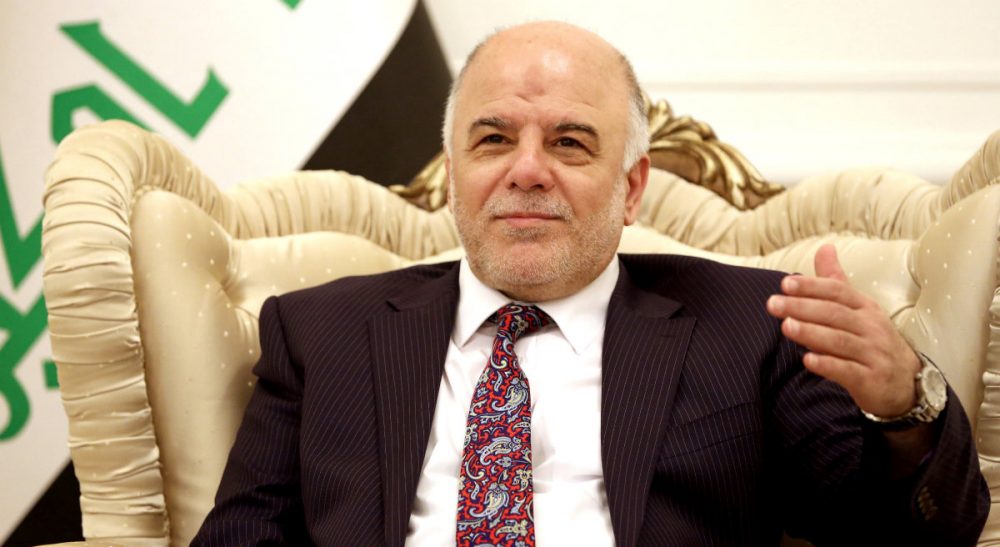

Will Iraq’s next prime minister, Haider al-Abadi, be any different?

It seems unlikely. Iraq has no tradition of inclusion. Saddam Hussein exploited Iraq’s divisions for his political gain. Tensions were exacerbated further when the Shia-dominated government in Iraq, supported by the United States, demanded de-Baathification, which purged all public sector jobs of high-ranking members of Saddam’s political party and helped spur an insurgency that led to civil war. Many Iraqis come from tribal traditions that view inclusion as a risk and compromise as a sign of weakness.

However, in my two decades of conflict resolution work around the world, I have seen consistently that building an inclusive government is the most common characteristic of a successful political leader in a divided society, while exclusion is the main driver of conflict.

One example to look towards comes from South African leader Nelson Mandela, who also came from a society that defined itself by tribal differences, not shared nationhood. He demonstrated to the world the power of inclusion in the early 1990s, when he included in his government the very leaders who had oppressed him.

Shortly after being elected president, Mandela went out of his way to signal to the white community — particularly the Afrikaners who feared a black-led government bent on revenge — that he was aware of their greatest worry. In his words and actions, he made it clear that they would not be annihilated as a community, stripped of their home and livelihoods and forced to flee their country of birth. He supported the creation of a government of national unity that was led by the ANC, the National Party and other parties representing all segments of South African society. Mandela served as president alongside his former oppressor, F.W. de Klerk, for three years.

Advertisement

Neither Maliki nor Morsi was able to rise above their history, experience and fears and govern differently than those who had governed them in the past. Neither was able to build inclusive governments that would have provided them the credibility and legitimacy to exercise power and transcend the vicious cycle of repression.

In Iraq, Maliki directly and needlessly marginalized, excluded and imprisoned Sunnis from governance. The rapid emergence of the Islamic State has been facilitated by Sunni Arab tribes, former Baathists and competing Sunni extremist groups who were shut out of any meaningful role in post-Saddam Iraq. These groups feared further marginalization under the heavy hand of Maliki’s Shia-led government.

In contrast, Mandela allowed many Afrikaner civil servants who worked for the outgoing regime to keep their jobs and pensions, which was both a symbolic act and a very practical and important political decision to signal inclusion and respect.

In Egypt, the Muslim Brotherhood, after decades of brutal repression and exclusion by successive military governments, rode to power on the heels of the Arab Spring and governed like their former repressors. Non-Muslim Brotherhood parties, including hard line Islamist groups like the Salafis, were marginalized and excluded from any role in governing the nation.

The failure to build an inclusive government and the brutal nature of the new regime led to massive street demonstrations that led to the imprisonment of President Morsi, the banning of the Muslim Brotherhood, the restoration of a military-controlled government and a strike against political Islam in the Arab world.

Maliki and Morsi did what was done to them and had no instinct or imagination to see the importance of including others or conveying that they understood the deepest fears and anxiety of their adversaries.

Recognizing the power of inclusion is simply and profoundly a matter of imagination, courage and leadership.

As nations struggle with diversity, and the world witnesses a growing trend to identify by sect, tribe, race and ethnicity over any sense of shared nationhood, understanding the fears of the other and building governments based on inclusion will be central to the successful exercise of power.

Will future Iraqi and Egyptian leaders learn this lesson from Mandela’s example? Was the exclusion, humiliation, suffering and killing of blacks in South Africa so very different from Iraq under Saddam Hussein that the example doesn’t fit? Could President Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood have learned any lessons when they had their chance at power? These leaders certainly had no experience with inclusion, but neither did Mandela.

Recognizing the power of inclusion is simply and profoundly a matter of imagination, courage and leadership. It is the imagination to think and act differently, the courage to overcome your fear of compromise and desire for revenge, and the leadership to stand up for an ideal against the will of your community and the hostility of your enemy. Mandela knew that, and other leaders such as al-Abadi would benefit from following his example.

Related: