Advertisement

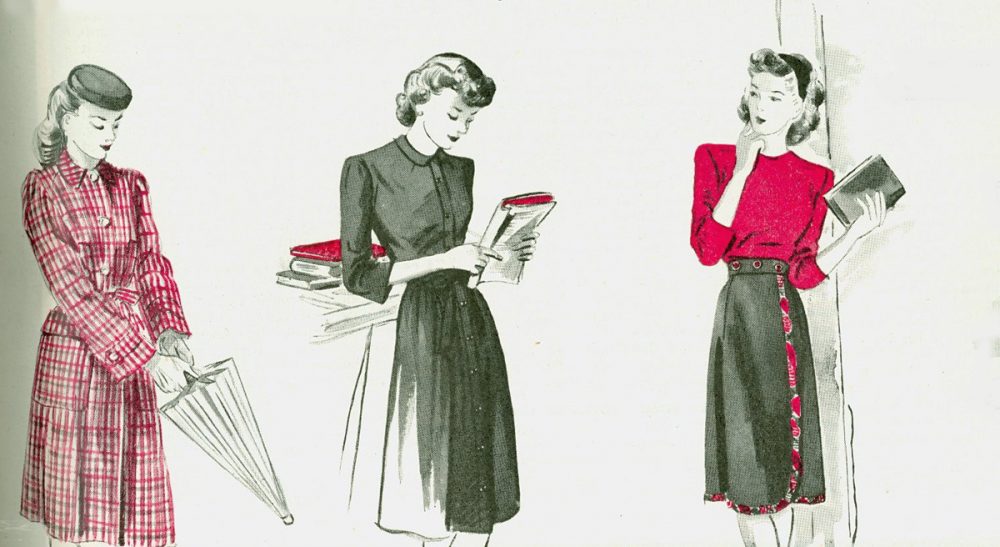

It's Okay To Love Fashion: On The Substance Of Style

When I turned 13, my grandmother gave me my first Vogue subscription and tube of lipstick. Always well turned out, she educated me in the other elements of style: why dresses cut on the bias are so flattering; why an empire waist (pronounced OM-peer, of course) best suited my small frame; the difference between silk dupioni and crêpe de chine; where to buy the best cashmere sweaters.

My grandmother was also a woman of substance. She had graduated first in her high school class and earned a baccalaureate degree in premed from Simmons College. After raising her son, she taught math to community college students. (She noted with pride that she had honed her math skills tutoring MIT students in calculus when she was an undergraduate.)

...I waited outside a classroom, flipping through W, the oversized fashion magazine. 'Aren’t you too smart for that?' a classmate asked. I put the magazine away and pulled out a course handout.

My grandmother could hold her own discussing world politics and current events with anyone in any crowd. She read the papers daily, and she prized staying informed. Her example taught me that smart women and fashion are not mutually exclusive, and that a keen attention to detail in one’s clothing only underscores one’s general thoughtfulness and seriousness.

Then I went to graduate school and learned that not everyone shares this view.

This dawned on me as I waited outside a classroom, flipping through W, the oversized fashion magazine. “Aren’t you too smart for that?” a classmate asked. I put the magazine away and pulled out a course handout.

I didn’t understand the problem. I was a reader, a thinker and a writer, just like my colleagues. But I also loved fashion, would swoon over a neckline, moon over the drape of a tropical wool.

During those years, Carrie Bradshaw was the reigning pop culture and fashion icon, and I was equally invested in my education in Manolos and Milton. But I kept the depths of my interest under wraps, saving fashion glossies for home and pulling out The New Yorker or The Economist in public.

I was occasionally embarrassed by my commitment to fashion, as I was when I took my seat at a conference dinner between two noted academics in my field, and one remarked, “Oh, you’re the one with the dress.” Not, “You’re the one who just delivered the paper.” My dress – a tasteful navy ponte knit Lilly Pulitzer with a print of interlocking hot pink high heels – was worthy of attention, I thought. But so was the quality of the talk I had just given.

Advertisement

Some of my students seemed to think that my interest in clothes and my vocation as a college professor were incompatible. One semester, some female students revealed that they had kept a list of my outfit combinations, watching to see if I would repeat an ensemble. There were student evaluations that rated my course content and clothing. This had the effect of making me want to blend in with the blackboard.

Women have always been judged by their appearance, not least by other women. In 1792, Mary Wollstonecraft advocated for female agency in her treatise, “A Vindication on the Rights of Women.” She also dismissed fashion by suggesting that a woman’s interest in costume is oppressive and detracts from her seriousness. “An air of fashion, which is but a badge of slavery…proves that the soul has not a strong individual character.” As I have learned, these perceptions persist in the 21st century.

I was <em>equally</em> invested in my education in Manolos and Milton. But I kept the depths of my interest under wraps, saving fashion glossies for home and pulling out The New Yorker or The Economist in public.

There is a fine line between fashion and frivolity. Women who work in fields requiring a high degree of education and training – law, medicine and academia, to name a few – walk that line. Show too much interest in your clothes, they say, and you seem too devoted to superficial matters. They describe a double standard of having to dress down to be taken seriously, yet dress just feminine enough to fit in with preconceived notions about how women should dress.

In the March issue of Elle magazine, the Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie asks, “Why Can’t a Smart Woman Love Fashion?” She can. As fashion editor Cynthia Durcanin has said, “Fashion is a state of mind. A spirit, an extension of one's self. Fashion talks, it can be an understated whisper, a high-energy scream or an all-knowing wink and a smile. Most of all fashion is about being comfortable with yourself, translating self-esteem into a personal style.”

What better way for the smart woman to project her confidence than through her clothing?

Last week, I pulled out my grandmother’s wedding album. My young daughter and I admired the photographs of her in her Parisian gown.

“She was so stylish,” said my daughter.

"And so smart," I said.

Related: