Advertisement

Cosby Rape Allegations: It's Time To End The Statute Of Limitations In Sexual Assault Cases

In the age of DNA, why are there still statutes of limitations in sexual assault cases? In an era that venerates transparency, why are confidentiality agreements still allowed to shield perpetrators and silence their victims?

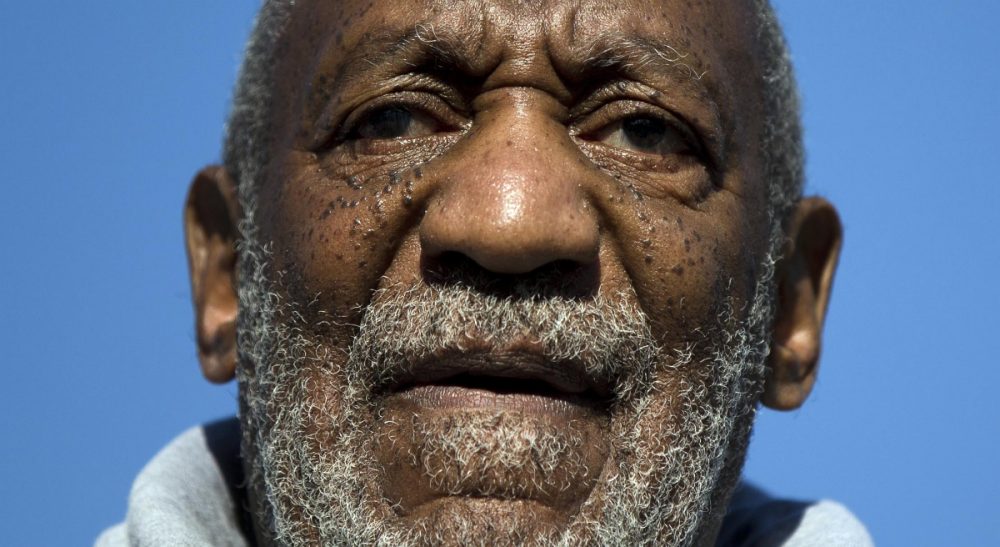

Those questions occur in response to recently revived allegations of serial rape against Bill Cosby, the comedic patriarch of the long-running television show that bears his name.

I do not know whether Cosby is guilty of the charges engulfing him. Neither do those who would convict him based on the number of accusers and the similarities in their accounts. Neither do those who, conflating the man with his TV persona, would reflexively exonerate Cliff Huxtable as incapable of such crimes.

There is a reason we have a criminal justice system, after all.

All but one of the more than a dozen women who have accused Cosby of sexually assaulting them across four decades did not seek criminal charges, concluding — reasonably but regrettably — that a crime which is always difficult to prove would likely be impossible against a wealthy defendant who was a beloved national icon. That decision has left them no court but the court of public opinion in which to air their accusations.

It is 2014. Advances in DNA testing mean that cases once beyond the reach of prosecutors can now be tried.

It’s the wrong venue.

As unreliable a setting as the courthouse historically has been for those victimized by sexual predators, it is the process we have and the one we have the best chance of reforming to more fully realize our legal ideal of a fair hearing for accused and accuser alike.

We could start by eliminating the statute of limitations in sexual assault cases and outlawing confidentiality agreements in the settlement of civil lawsuits that involve alleged criminal behavior.

Why should a rape victim's access to the courthouse depend on when the crime was committed? There is no statute of limitations on murder because no one thinks the passage of time should shield a killer from answering for his crime. Why should perpetrators of the soul-killing act of rape have such a legal escape hatch?

In 34 states they do, with laws that require prosecutors to file charges within time periods ranging from three months to 30 years. In Massachusetts, the statute of limitations is 15 years. Victims’ advocates have been filing legislation to eliminate all time limits for decades on Beacon Hill but a Legislature dominated by defense lawyers has been disinclined to act. Even the clergy sexual abuse scandal of a decade ago did not remove that barrier to bringing predators to account.

Advertisement

It is 2014. Advances in DNA testing mean that cases once beyond the reach of prosecutors can now be tried. The old arguments of the defense bar for narrowing the time to bring charges — that memories fade, that alibi witnesses die, that false accusations are common — apply less in a world where DNA can implicate, or exonerate, a suspect.

Only last summer, during her unsuccessful campaign for governor of Texas, Democrat Wendy Davis urged the elimination of the statute of limitations on rape after a high-profile case there underscored the injustice of such time limits. Lavinia Masters had been sexually assaulted in 1985 but her rape kit was not tested until 2005. Even though the DNA in the kit matched that of a man already incarcerated for sexual assault, he could not be prosecuted because the 10-year statute of limitations had expired.

Why should perpetrators of the soul-killing act of rape have such a legal escape hatch?

The one woman who did go to authorities about Cosby was Andrea Constand, a former director of operations for Temple University's women's basketball team and a college basketball star herself. She told police in 2005 that Cosby had drugged and raped her in his Pennsylvania home the year before. When prosecutors failed to charge him, citing insufficient evidence to meet the standard of proof required for conviction in criminal court, Constand filed a civil lawsuit for more than $150,000 in damages, saying Cosby’s actions had caused her "to suffer severe emotional distress, humiliation, embarrassment and financial loss." They settled the case out of court, with a provision that prohibits her from disclosing the terms.

Imagine if Constand had refused to settle, had refused to sign an agreement that silenced her. Imagine if she had made good on her threat to take the stand against Bill Cosby in civil court, where a lower standard of proof applies. Imagine if she had stood alongside the 13 other women her lawyers said they had assembled as witnesses to testify that Cosby had drugged and raped them, too.

It would have been a lot to ask of Constand — courtrooms have long been hostile places for sexual assault victims — but we would be having a different conversation today had she found the courage to confront Cosby in court. We do not know the terms of their settlement, but we do know that whatever admission Cosby might have made, it is now legally beyond the reach of the criminal justice system and all those other women who are left to make their case on "Entertainment Tonight."

Related: