Advertisement

This Thanksgiving, I'm Thankful For The Atlantic Cod

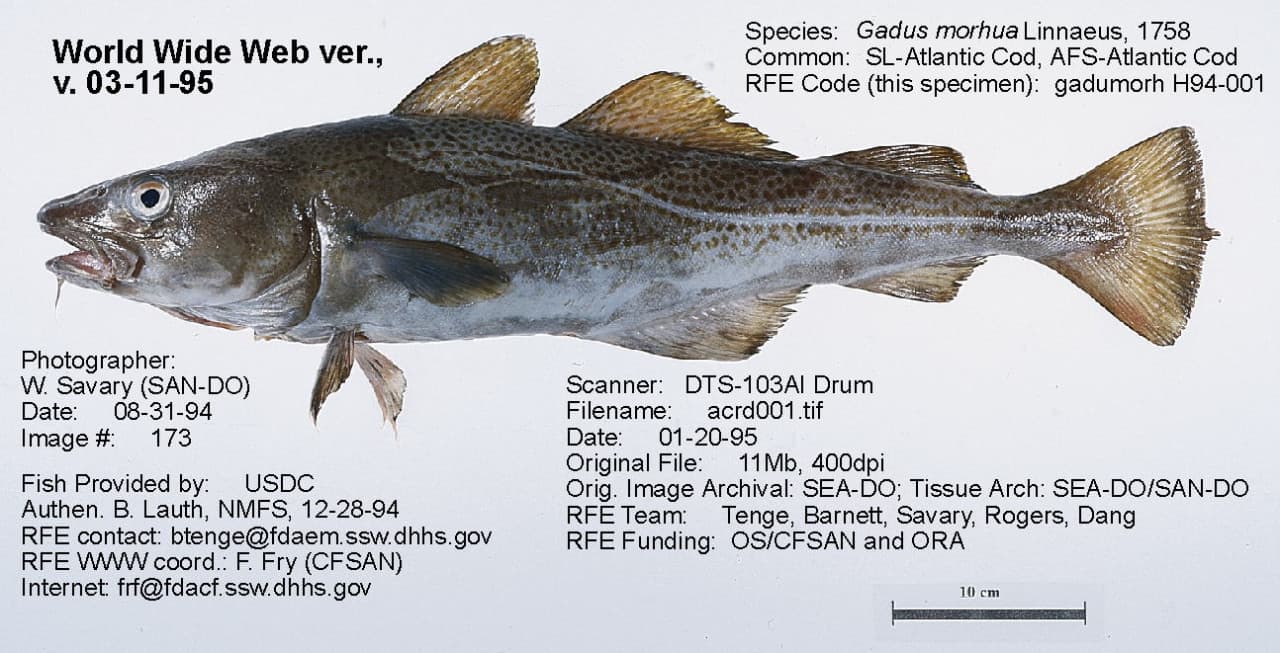

According to recent news reports, the Atlantic codfish is disappearing from the Gulf of Maine. That glorious creature, which was for centuries dominant in those waters, is now barely present. The few that remain are much smaller than their ancestors, even when full grown. Cod have been overfished, and this pressure, together with the way climate change is quickly warming the Gulf waters, is making it hard for them to reproduce fast enough to repopulate their meager numbers.

Codfish have long been at the heart of New England life. Early explorers stuttered with awe at the abundance and size of the ones they found in the Gulf of Maine. When fishermen hauled them back home to Europe, the sight of the big cod for sale in the market made the fantasy of the New World tangible.

the cod symbolizes the extraordinary natural abundance that North America has offered to all of us.

To me, the cod symbolizes the extraordinary natural abundance that North America has offered to all of us. They helped create the wealth that allowed the earliest European settlers to take hold and prosper, and the United States to be born. Jeffrey Bolster tells us in his remarkable book about New England fishing and environmental history, “The Mortal Sea,” that by the time of the American Revolution in 1775, the 13 colonies had the highest per capita gross domestic product of any country in the world. Fishermen, boat builders, mariners, stockholders and merchants all labored to create that wealth; and cod played their part.

Let me translate: my immigrant grandparents, who arrived at the beginning of the 20th century, were not fishermen. I doubt either one knew a hook from a piece of bait. But they could never have left their impoverished countries and made lives here had it not been for the wealth generated by harvesting cod — and so many other creatures.

I’ve been following the fate of gadus morhua for a while now as I’ve been researching a book about fishing on an island in the Gulf of Maine. Their prospects haven’t looked great for decades. In the course of the 20th century, fishing technology became too sophisticated, and the world population grew too quickly. With so many hungry folks in search of protein, and so many big boats with big nets and sonar, codfish had nowhere to hide. We lifted millions of tons of them out of the sea, and we ate them. They tasted good; and we thought they would replenish themselves no matter what we did.

Sadly, the notion (supported for a time by scientists) that the creatures in the sea were infinite, a magic lantern we could just keep rubbing, turned out to be a fairy tale. Now, with cod — and so many species — on the wane, we’re going to have to act from a new kind of self-interest if we want the seas to thrive again. To save the Atlantic cod, if it’s not already too late, we will need to make good decisions rather soon.

Advertisement

It’s ridiculous to have the fate of the ocean’s creatures in human hands. What sensible person would ever have wished for that? Yet, for now, it seems to be so. And lots of living things with fins and shells are counting on us to step up our game.

You might say our task is as terrible and marvelous as was that of the early settlers, but it's the opposite. Imagine the Gulf of Maine as it was when the first Native Americans saw it 12,000 years ago, or more lately in the 16th and 17th centuries, when John Cabot and Samuel de Champlain and other Europeans arrived to find it teeming full of fish. Imagine it now, so relatively depleted. They began emptying it. We have to focus on refilling it. I believe we can. (Preserving local fishermen, who might work both fishing and monitoring, seems to me to be part of that effort.)

our first step is to move ourselves toward a worldview in which other species are no longer construed by us as an entitlement.

Much is going to be fought out among politicians, corporate fishing businesses, environmental groups and lobbyists — the people called “stake holders” (as if the rest of us aren’t). But we can influence them, and our first step is to move ourselves toward a worldview in which other species are no longer construed by us as an entitlement.

As part of your Thanksgiving this year, why not do a small thought experiment: Sit somewhere quiet for a few minutes, and create a virtual parade in your mind. Let all the cod, halibut, swordfish, Atlantic salmon, bluefin tuna, beaver, great auks, carrier pigeons, and on and on and on ... line up and process before you; let their ghosts drift by. In real time it might take decades. But you can choose the pace. As their ranks float by, just say “thank you.” No guilt, blame or recrimination. Just thank you. We have benefited from their sacrifice; we are harmed now by their depletion. This Thanksgiving, let’s consider our debt to the whole faltering animal world, but particularly the sacrifice of the Atlantic cod for our well-being. Saying thank you and really meaning it is, of course, not enough; but because shifting perspectives is part of changing actions, it just might help.

Related: