Advertisement

A Boston Historical Marker's 'Inimitable' Anti-Semitism, And Why It Needs To Go

Not long after moving from New York City to Boston in the early 1990s, I crossed the Big Dig construction site to explore the North End. I absorbed the neighborhood’s rich history — the Old North Church and its place in the American Revolutionary War; the Niles Building at 27 School St., where an Italian immigrant named Carlo Pietro Giovanni Guglielmo Tebaldo Ponzi – Charles Ponzi – plied his crooked financial schemes; and the successive waves of immigrants from Ireland, Eastern Europe and Italy.

I found it hard to believe that this was a legitimate historical plaque, intended to be educational and factual.

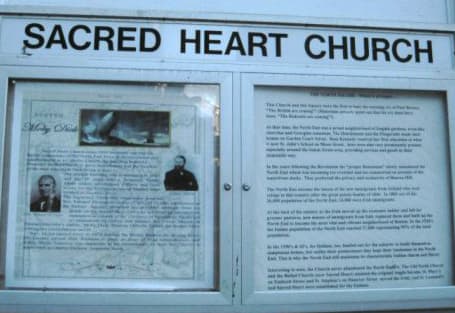

After visiting Paul Revere’s house, I noticed a red brick church with tall arched windows. Wondering how old it was, I read the historical marker on its façade. It wasn’t a professional-looking, engraved or cast-metal plaque; instead, there were two sheets of what seemed to be heavy paper, perhaps laminated, posted side by side in identical locked glass cases.

I learned that the building was constructed in 1833 as the “Seaman’s Bethel,” a church or mission for sailors. In 1884, a group of Italian Catholic immigrants bought the building, and, in 1888, it became the Sacred Heart Church.

In its summary of North End annals, the historical marker notes, “Jews were also prominently present, especially around the Salem Street area, providing services and goods in their inimitable way.”

In their inimitable way? I was surprised, not quite believing what I had read. Take that sentence and substitute another group — perhaps Irish, Italian, Chinese or African-Americans — add a stereotype or description, and conclude with “in their inimitable way.” Would that sign last in this or any other city?

As a newcomer to Boston, not yet smitten with the Red Sox, I thought, New York would never tolerate — or even create — such an obtuse, amateurish historical marker. I found it hard to believe that this was a legitimate historical plaque, intended to be educational and factual.

Granted, the sign’s subtle anti-Semitism certainly wasn’t the overt and malicious brand that is the hallmark of Neo-Nazis and white supremacists. Nor was it the more genteel “country club” anti-Semitism of exclusion. Instead, the sign exemplified a milder brand of stereotyping — “good with money” or “sharp in business.”

This stereotype never made sense to me growing up in a family of artists, intellectuals, academics and shrinks. My uncle the psychiatrist invested in silver in the 1970s and lost a fortune in the infamous 1980 silver crash. My father the psychologist didn’t act on a patient’s tip to buy Xerox stock in the company’s early days, because he considered it unethical and an abuse of confidentiality (moreover, the product seemed far-fetched).

Years went by without my seeing or contemplating the sign, until I went to a street festival in the North End last summer. I sampled pastries, bought spices and suddenly remembered the plaque.

Would it still be there? In my two decades in Boston, the city had changed dramatically: Restored townhouses and soaring real-estate prices in the South End. Chic lofts and bars in a Southie unrecognizable to Whitey Bulger. A food scene revitalized by chefs reinventing formerly fusty cuisine. The stylish Liberty Hotel where the Charles Street Jail’s looming wreck once stood. The ICA and sleek modern architecture along a newly popular waterfront. A restored and expanded Boston Harborwalk. Fountains and flowers in the Rose Kennedy Greenway in place of an elevated eyesore of a highway. A refurbished Kenmore Square with an expensive hotel, not to mention a winning Red Sox team. The city also witnessed a popular African-American governor, a majority minority population and the country’s first same-sex marriages.

Would the “inimitable” plaque still be there, I wondered, or would it have disappeared with the city’s modernization? I hurried to the church. The plaque was intact. Perhaps the keys to the plaque’s locked glass cases had long ago been lost.

Taken to an extreme, that 'otherness' is what made possible the massacre of Jews in World War II and the willingness of ordinary citizens to let it happen.

The sign reminds me that, even in America, even in a dynamic, progressive city like the new Boston, Jews might still, to some extent, be considered “other,” a group with its own “inimitable way,” a group that is not unequivocally part of the city or nation in which we live. One need look no further than the recent targeted murders of Jews (who turned out not to be) in Overland Park, Kansas, for sorry proof that this is so.

It’s happening in Europe, too, with the rise of anti-Semitic politicians in several countries, the ugly chants of soccer fans in Poland, Holland and England (“Jews to the gas” and “Jews burn the best”), and the targeted murders of Jews in France, Denmark and Belgium.

Taken to an extreme, that "otherness" is what made possible the massacre of Jews in World War II and the willingness of ordinary citizens to let it happen and even participate.

The sign, then, should not be dismissed as some benign or quaint form of anti-Semitism. It should not exist as an educational marker in Boston’s historic North End. Boston can — and should — do better.