Advertisement

April Is National Volunteer Month. What Would Ayn Rand Say?

April is National Volunteer Month. Over the past 40, years I’ve donated my time and services in dozens of ways. Since retiring, I do so far more often. This commemorative month seems an appropriate time to reflect upon why I enjoy unpaid activities. It’s also got me thinking about Ayn Rand.

Howard Roark, the architect protagonist of 'The Fountainhead,' never took an afternoon off from conceiving bold structures to dabble in community service.

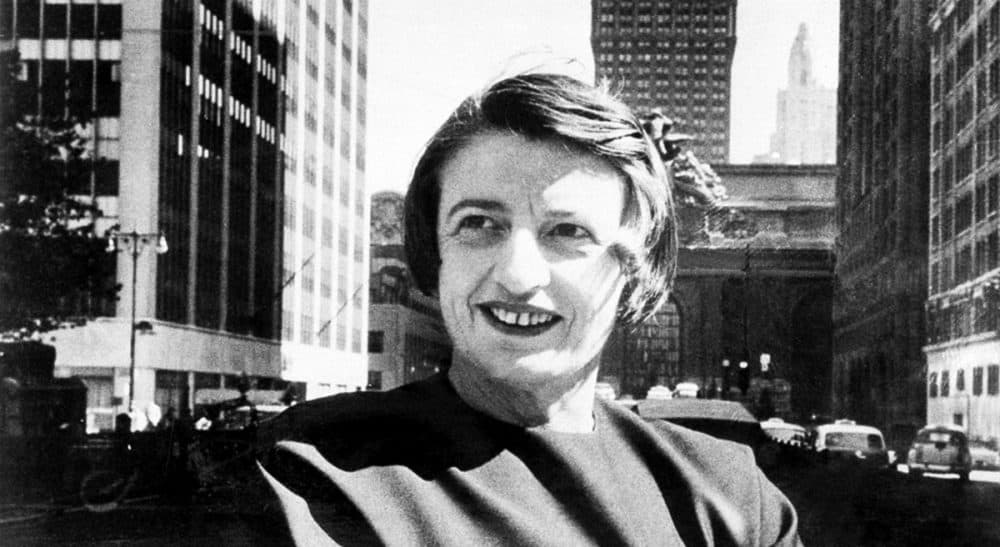

Rand was all the rage when I came of age in the 1960s. The libertarian darling authored the hedonistic novels “The Fountainhead” (1943) and “Atlas Shrugged” (1957), as well as a philosophical manifesto, “The Virtue of Selfishness” (1964). Rand once said, “If any civilization is to survive, it is the morality of altruism that men have to reject.” What light could the originator of Objectivism possibly shed on volunteering?

Merriam-Webster defines altruism as “unselfish regard for, or devotion to, the welfare of others.” Since Rand champions selfishness, it follows that she regards altruism as antithetical to human nature and an obstacle to progress. But if Rand’s perspective is knife-edge sharp, Merriam-Webster’s is too rosy. People do not give away their time and skills because they’re selfless. People volunteer because their self-interests are broader than pecuniary measures. They may not receive money for their effort, but they receive other rewards.

For most of my life, my volunteer pursuits mirrored my architectural career. There was logic to my 1978 Vista stint renovating houses in West Texas, designing The Boston Living Center pro bono in the 1990s, building Musician’s Village in New Orleans post-Katrina, and constructing a school in Haiti after the 2010 earthquake.

Though I’ve stopped working for money, I continue to provide architectural services for projects in the developing world. But more recent volunteer gigs are unrelated to design and construction. After a lifetime focused on analysis and technology, I enjoy connecting with individuals: teaching, mentoring, sometimes even touching.

I tutor an immigrant from Morocco through YMCA International; Rida is preparing to take his TOEFL exam. I give individual yoga and stretching sessions to middle aged men with bad backs, sciatica, even Parkinson’s. I spend one morning a month at Career Collaborative, a Boston-based program that teaches job-getting skills to adults with challenging work histories.

Ayn Rand would be flummoxed. Why decipher gerunds and participles, ease an aging man into pigeon pose, or suggest how an Ethiopian immigrant can leverage 7-11 experience into a job with benefits? I should be getting paid real money for doing what I know best. Howard Roark, the architect protagonist of “The Fountainhead,” never took an afternoon off from conceiving bold structures to dabble in community service.

Advertisement

Yet, I don’t call what I do altruism, a somewhat paternalistic word with elitist overtones. I enjoy doing these things. My daily life doesn’t provide opportunities to meet African immigrants or Parkinson’s patients; my interactions with minimum wage workers are typically limited to check-out counters. Getting to know such different people broadens my experience, deepens my empathy, and makes me more appreciative of the privileges I enjoy. Being an architect shapes the world in a concrete yet detached way. Direct interactions through volunteering generate other satisfactions.

If altruism means selfless, don’t call me that.

Self-interest is not fixed, it expands and restricts as our circumstances ebb and flow. When we’re poor, hungry and destitute, our self-interest is focused on survival. But when we reach a place where life’s essentials are met, we seek more complex satisfaction, working our way up Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs in search of self-actualization. Unleashed from mere survival, self-interest extends beyond the limits of our skin. It becomes entangled with the well-being of others until, ultimately, we acknowledge that our self-interest depends on others having what they need, as well. Once we have enough, true security results from contributing and sharing rather than hoarding.

I am in accord with Ayn Rand; no one acts except in his self-interest. But I am fortunate to be in a position where my self-interest transcends dollars and cents. If altruism means selfless, don’t call me that. But I’ll continue to volunteer, in the hope that I might offer value to someone else and for the certainty that I will receive benefit.