Advertisement

What's Wrong With The Nobel Prize In Literature

Through its award in literature, the Nobel Prize Committee seems to be telling readers that the most important thing we can remember is that history repeats itself. If the selection of Belorussian writer Svetlana Alexievich as this year’s recipient is any indication of that belief, then the committee has succeeded. Over the last decade, the prize has been awarded to a succession of fine writers. Time and again, however, the committee’s reasoning appears rooted in a politically charged reading of the relationship between history and current affairs. Literature, as such, often appears to be a secondary consideration.

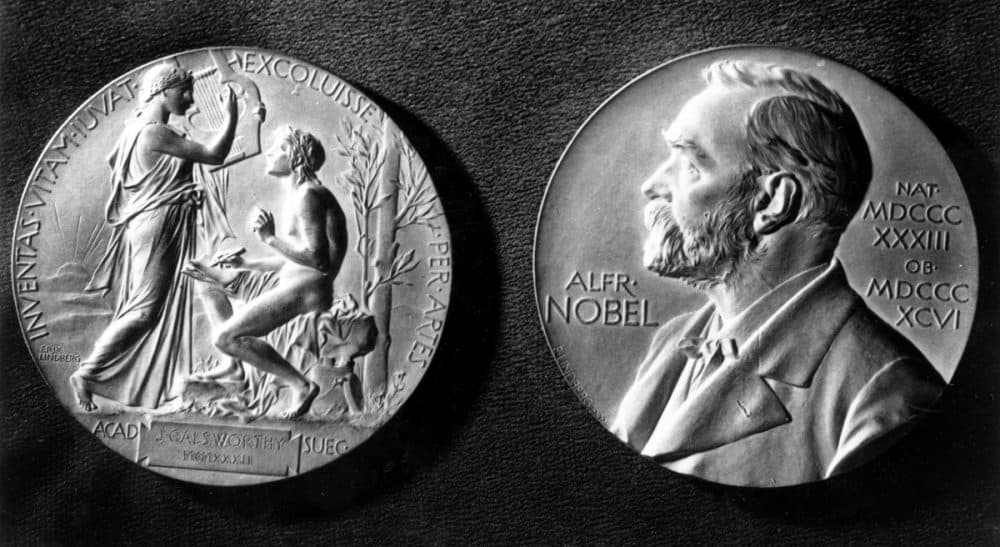

Alfred Nobel’s notoriously confusing will gave birth to the prize in literature, which has been awarded to 111 authors over the last 114 years. Nobel wrote that the award should go to any kind of writing that was, "the most outstanding work in an ideal direction […] during the preceding year.” This was ultimately expanded to recognize a writer with a body of excellent work instead of an individual piece, and for the most part it has. From Toni Morrison to Tomas Tranströmer, some of the greatest writers in the world have been recipients.

The disturbing, tacit insistence that trauma and suffering are so disproportionately necessary for transcendence does not fit [the original] mandate...

In 2005, the selection of British playwright Harold Pinter was the first sign that the committee’s criteria for giving the award had shifted. Throughout his career, Pinter wrote an undeniably exceptional array of plays. He was also a fierce critic of the second Iraq War, gaining attention for his scathing comments about British Prime Minister Tony Blair, and his comparison of George W. Bush to a Nazi. Pinter’s art and his politics were often inseparable, but it was evident at the time that the committee’s reasoning was based on their personal affinity for the latter.

In and of itself, this was not necessarily unusual. For decades the committee’s selections sometimes took into account the political circumstances that influence authors and their art. What was unusual is the subsequent selection of a string of authors for very similar reasons. Since Pinter, the award has largely gone to writers whose works grapple with atrocities and cruelty in ways that seem convenient for inferring that the committee has certain beliefs about present-day politics.

From unjust regimes in Russia and China, to war crimes and violence in Europe and South America, writings by the Nobel laureates in literature have neatly intersected with the U.S. wars in the Middle East, the ascent of Vladimir Putin and the resurgence of the European right-wing. This noticeable coincidence has been difficult to criticize. Few people want to be seen challenging the selection of a writer whose works deal with memories of the Holocaust or death squads. Moreover, as Americans, we seem predisposed to believe that the Nobel committee’s considerations must have depth that places them beyond reproach.

Yet, this consistent focus on one type of writer comes at the expense of many others, while also risking the unendorsed politicizing of works that may not have been written for the 24 hour news cycle. In addition, there is no reason to reflexively believe that the underlying considerations are so sophisticated. A European professor is not automatically any more astute about the relationship between literature and politics than a couch-surfing American who watches every new show on Netflix.

The substance of the committee’s deliberations are unknown, but this much is clear: Most of the authors fall into two categories, with some overlap -- obscurity of the author to most readers around the world, and writing that confronts historic violence in ways that have current, concrete meaning. The problem is, neither of those considerations were intended to be criteria for this award.

Alfred Nobel sought the 'ideal direction.' It is difficult to think that he believed the ideal to be so frequently lacking joyous, expansive, curious or surreal writing.

Alfred Nobel sought the “ideal direction.” It is difficult to think that he believed the ideal to be so frequently lacking joyous, expansive, curious or surreal writing. It is equally hard to accept the notion that the ideal is so-often a reductive, death-obsessed homage to the resilience of the individual in the face of an abusive civilization. Yet this is precisely what seems to have happened to the prize. In the committee’s comments on their selection of Alexievich, they hailed her writings as a “monument to suffering and courage in our time.”

The scientific Nobel prizes measure concrete achievements, and while the peace prize has gone to many undeserving recipients, the purpose of its existence is clear. Literature is the only artistic prize awarded by the Swedish Academy. One can be reasonably certain that Alfred Nobel’s ringing admonition to seek the good in the world means that the literature prize should celebrate writing as a broad art form that delights, wonders and revels as often as it plumbs the connections between travesty and the political realities of our world.

The disturbing, tacit insistence that trauma and suffering are so disproportionately necessary for transcendence does not fit this mandate, and the authors who have been selected should not be a convenient meme for a committee’s political ideology, even if the causes are just. If it is the case that history repeats itself, perhaps the long arc of history will swoop in next year, and revive the ideal that once made this such an important award.