Advertisement

The Real Legacy Of War: Some Thoughts On Veterans Day

In the midst of working this week on my book about fishing on Vinalhaven in Maine, I found myself unexpectedly thinking about Veterans Day when I read a few sentences written by an islander who served in the Civil War.

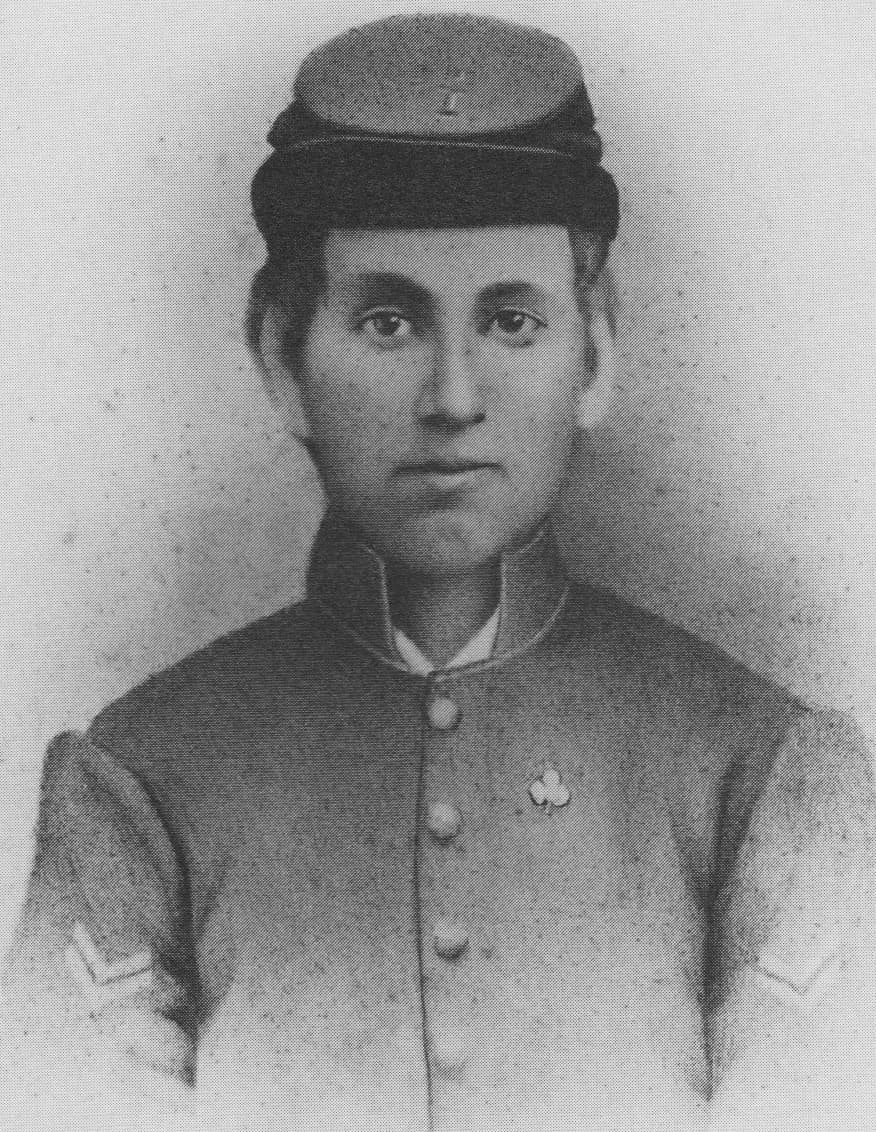

The Civil War started on April 12, 1861, and 180 men from the small island would serve in the Army and Navy before war’s end. In August 1862, the 18-year-old Woster Smith Vinal joined the 19th Maine Regiment, and had quite a tour. Woster was present at many of the major battles — including Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville and Gettysburg.

Worse, he, along with his two island friends, Alden Dyer and Joseph Norton, were captured and imprisoned in June 1864. Woster survived first Libby Prison in Richmond and then the terrible Andersonville prisoner of war camp in Georgia before returning to Vinalhaven, where he lived to be 93.

Some years after returning home, contributing to a history of his regiment he admitted, “I have purposely omitted from this account the scenes of indescribable cruelty, suffering and horror in those awful prison pens. No one can know what our boys suffered, except the knowledge be had through bitter experience. It all comes back to me like an awful nightmare after all the years that have passed since the long months of hunger, sickness and brutality.”

Except the knowledge be had through bitter experience.

No wonder many veterans now wince when we blithely “thank” them for their service. Those of us who haven’t survived battlefields and prison camps have but the dimmest idea whereof we speak. We lack the bitter experience, and our imaginations aren’t entirely up to the task of grasping and bearing the survivor’s plight. We know that dead is dead. But we can’t fully bear to understand how war’s great prerogative is to sear terror into the minds of soldiers with such ferocity that they often cannot ever leave it behind.

No wonder many veterans now wince when we blithely 'thank' them for their service. Those of us who haven’t survived battlefields and prison camps have but the dimmest idea whereof we speak.

Until the 20th century, and really until the Vietnam War, we preferred if people suffered in silence, so that none but their intimates knew the full extent of their ongoing pain. Now we speak publicly about PTSD, though our treatments are still often inadequate and our services ungenerous in proportion to the need. But more to the point, I worry that even in giving the trauma an acronym, we continue collectively to minimize its real and ongoing impact.

Loneliness radiates from Woster’s words. He has seen and experienced a living hell. Like so many who have suffered terribly, he hesitates — or refuses — to transmit what he knows. He has told us that words are insufficient. Maybe it’s too much even for him to write.

The lesson we might best take from his decision to stay publicly silent is a sober reminder that the task for those of us who have been spared personal involvement in war is — whatever we say or don’t — that we not respond glibly or dismissively. That we not pretend we know what we’re talking about. Otherwise, we risk increasing, not diminishing, the profound aloneness that is so often the real legacy of war.

Quotations and material from writings by Calvin Arey for the Vinalhaven Historical Society. Annual Newsletter, 2004.