Advertisement

'F' For Faulty: Rating The New Restaurant Letter Grade System

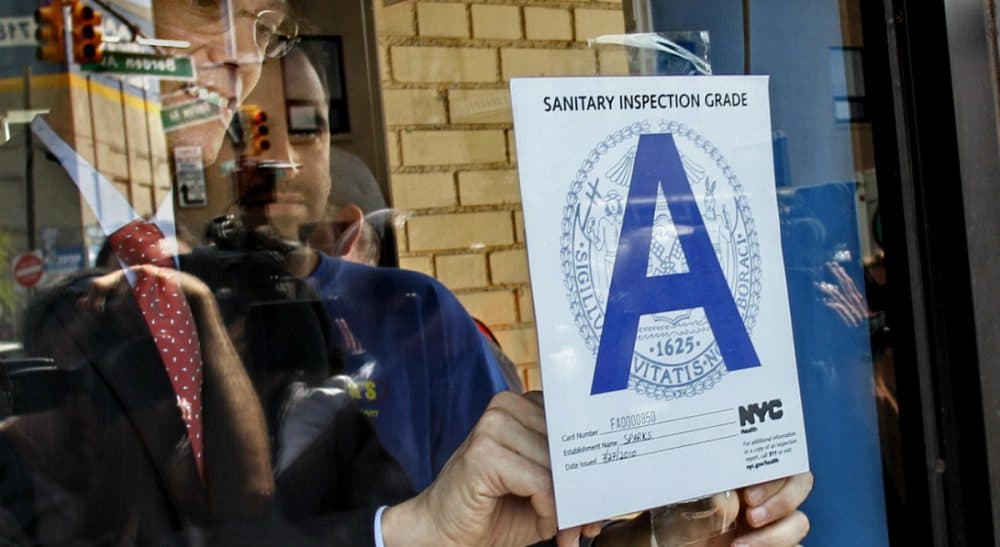

Boston — belatedly — is joining the crowd, promising to start rating restaurants by the familiar letter grades (“A,” “B” and “C”) that appear in the windows of dining establishments in New York, Los Angeles and numerous other American cities.

The grades are a source of consternation to restaurateurs. They worry that spot inspections can trip them up on a bad day. They wonder about rules that sometimes seem arcane and senseless. And some fear, as well, that grades are more a function of who you know or who you pay off (not, of course, that something like that could ever, ever happen in Boston…).

Meanwhile, the public loves the grades. They’re simple and easy and can be a source of much amusement too, especially when highfalutin places (such as, in one celebrated case, Thomas Keller’s Per Se in New York) get “Bs” or “Cs.”

Within the food industry, there’s a strong sense that health inspections are more about complying with complicated and sometimes outmoded rules than they are about safety.

What’s less certain, however, is that the grades improve public health.

Boston’s grades won’t tell you whether the food is delicious. That’s the job of critics and carping diners posting on sites such as Yelp and Open Table. Rather, the city’s report cards are ostensibly about whether a dining establishment is safe: that is, whether the food you consume might send you to the hospital or -- gulp -- even the morgue.

How often does that happen? The Centers for Disease Control figures 1 in every 6 Americans get sick from food-related illnesses each year, and that about 128,000 of those are hospitalized or die. The CDC also estimates that perhaps (and this is a big perhaps) just over half are from dining out. That’s about 65,000 diners sickened each year, which seems a scary number until you realize how frequently we eat out. Americans consume more than 30 billion meals a year outside of their homes, meaning that about 99.999 percent of the time we don’t get seriously sick from our meals. That’s a safety record I bet few other industries can match.

Still, as they say, one is one too many, so in theory the grading system should be welcomed because it will help make our meals even safer. Yet Boston’s introduction of grades doesn’t mean anything substantive is changing. Inspectors will go out as frequently as they did before, checking to see if eateries are complying with complex health code. The grades are just a shorthand way of summarizing the results of those inspections.

Right now those inspections can be found online at a section of the city’s website called the “Mayors Food Court.” It makes for interesting reading. To take one example, on August 21 inspectors visited Kenmore Square’s Eastern Standard — recently called “a perfect restaurant” by the Boston Globe — and found 14 violations. Most were minor but one was deemed critical (the aioli for the calamari wasn’t kept sufficiently cold). Luckily for Eastern Standard, on re-inspection a week later, most (but not all) of the violations had been resolved; the self-styled brasserie was allowed to stay open.

Sounds like a “B” to me.

As a fairly regular Eastern Standard customer, quite frankly, I don’t care. Within the food industry, there’s a strong sense that health inspections are more about complying with complicated and sometimes outmoded rules than they are about safety. Last month, for example, food poisoning at a San Jose restaurant made 80 sick -- even though the establishment had recently passed inspection.

the stuff restaurants get cited for on the Mayors Food Court are usually far less troublesome than what we do at home.

And in any event, a “B” or “C” grade says little about the relative safety of that restaurant compared to one with an “A” — it’s more a PR problem than anything else. All of those getting grades are, in fact, safe (at least as how “safe” is defined by the city’s code). If inspectors felt a place posed an immediate health threat, they wouldn’t grade it; they’d shut it down. Indeed, the stuff restaurants get cited for on the Mayors Food Court are usually far less troublesome than what we do at home. When I cook, for example, I don’t use plastic gloves when I handle food, I serve cheese at room temperature and I let meat rest for a while after it’s cooked. And I don’t like my aioli cold.

Come to think of it, maybe I’ll never eat at home again.

And one final worry about the grades. Yes, food-borne illness is a concern. But the biggest health concern with food is not about how it’s prepared but rather what we eat. American diets are too heavy in calories, carbs and sugars. Fast food places such as McDonald’s routinely get high grades -- the chains have lots of experience making sure they comply with codes. But just because your local Golden Arches has a big “A” proudly displayed in its window, that doesn’t mean you should, you know, actually eat there.