Advertisement

Not All Change Is Progress: Why The Globe Should Bring Back Paperboys (And Girls)

Lately, The Boston Globe has earned some unwanted headlines for problems with its new home-delivery service. Reporters, editors and other Globe personnel have left their warm beds and leapt into the breach, using their cars to deliver the print version of the paper to their precious regular subscribers.

I can sympathize.

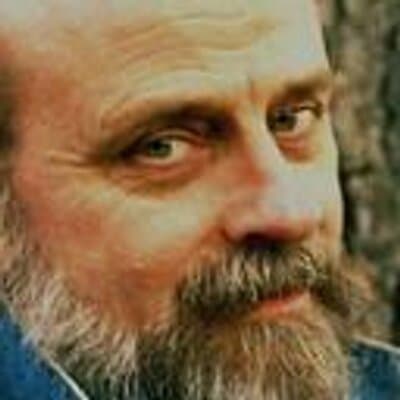

I delivered the Globe for nearly eight years, six days a week, in my old neighborhood in West Medford. It was a robust business that helped put me through college and taught me a number of life lessons — all in an era before corporate outsourcing and subcontractors.

I began my career as a paperboy (alas, papergirls were a rarity in those days) for the Globe in the winter of 1965 at age 10. Back then, paper routes were coveted, and the only time of year when a route became available was during the week or two after Christmas. The reason was simple: Paperboys all tried to hang onto their routes through December so as to reap the traditional Christmas tips. Once they had that windfall, they would quit. That’s how I got my break.

[My paper route] was, no doubt, the genesis of my life-long career in journalism.

The system worked like this: Sometime during the overnight hours, a truck would slow down outside our house and someone would toss out a bundle of newspapers. When my alarm clock went off, I would get up and get dressed, stuffing my feet with extra socks into the green rubber boots I wore most days in those snowy winters. I would bring the bundle of papers into the house, cut the string, and place them into a giant canvas bag that would hang from my shoulder.

On my very first day, I ventured out into the cold, dark morning, lugging my load of Globes like a tiny peddler. I had not memorized my route yet, so it took a long time. I had a list on paper of my customers and their addresses, but it was still so dark out that I had to stop under a streetlight, read the next few names, try to commit them to memory, then trudge along making deliveries until I needed to check the list again.

My goal: Get every paper safe and dry onto each front porch and get back home in time for breakfast and the walk to school.

Advertisement

Eventually, I got the hang of it and became more efficient. Getting a bike speeded things up. So did learning to fold the papers so that I could toss them onto porches from the street rather than walking up each front walk.

Weather permitting, these simple steps greatly increased my delivery speed, to the point where I was able to take on a second, adjoining route. With more territory, I was keen to step up my pace. So, I mastered the ultimate in suburban paper delivery: I slung the canvas bag over my shoulder and hopped on the bike. While riding “no-hands,” I would fold the papers as I went and toss them up onto the porches, without stopping. Now, I could get through my whole route in no time and focus my attention on the revenue model.

My system was pretty straightforward. I charged my customers whatever rate the newspaper established for home delivery. I was entitled to a share of that base figure, plus regular tips, and the Christmas bonuses. It was a pretty good business for a kid who could not even legally get a real job.

Yes, it was child labor, and it would have been illegal if the nation’s newspapers had not exempted themselves from all such legislation. Legally, I was considered an independent contractor. All I knew was that it put money in my pockets.

Besides, I started to get interested in the contents of all those papers. I started with the “funnies,” which were usually printed on the back page. As I got a little older, I moved forward through the paper, discovering sports and then general news. By the time I was a teenager, I kept reading about Yaz and Russell and Orr, but I also included a pretty steady diet of news about Vietnam, protests and the Beatles. This was, no doubt, the genesis of my lifelong career in journalism.

But as good as it was, the paperboy business had its challenges. For one thing, I saw more sunrises than I care to remember, and to this day, I hate getting up in the morning.

Another lesson was in customer relations. It was part of the paperboy’s responsibility to visit every house every Friday afternoon to collect that week’s subscription money. By going door-to-door, I couldn’t help but stay in touch with my customers. I learned who really cared about getting the paper inside the storm door, who left for work early, and who tipped well.

Globe readers would be delighted at the high level of customer service, and those kids would learn a thing or two about perseverance, efficiency, thrift and record-keeping.

Collecting also required me to learn a bit about book-keeping, because an astonishing number of my fellow suburbanites somehow couldn’t manage to scrounge up 50 or 75 cents at the end of the week. They seemed to be under the delusion that information should be free, or else they just couldn’t be bothered. So I had to keep accounts in a little ledger book.

Then, there were the dogs. A mutt named Tammy seemed to be put on Earth just to torment me, chasing me every morning for the sheer malicious pleasure of it.

Despite all the challenges, my route became so easy and so lucrative that I hung onto it all through high school. I would say the experience had a major formative influence on me, and I always thought it was a shame when the newspaper industry moved away from having paperboys (and girls) in favor of grownups driving around in cars and never stopping by to chat.

Not all change is progress. As the Globe struggles to tweak its home-delivery service, I might suggest that the newspaper’s executives consider recruiting a small army of boys and girls on bikes. Globe readers would be delighted at the high level of customer service, and those kids would learn a thing or two about perseverance, efficiency, thrift and record-keeping. They might even develop a real interest in the news.