Advertisement

If The Brain Is Dead, Are You?

A person diagnosed as "brain dead" is sustained on a ventilator. Is this person dying or dead?

On my blog, I referred to the patient as dying. A reader corrected me. He said that, in fact, the patient was dead.

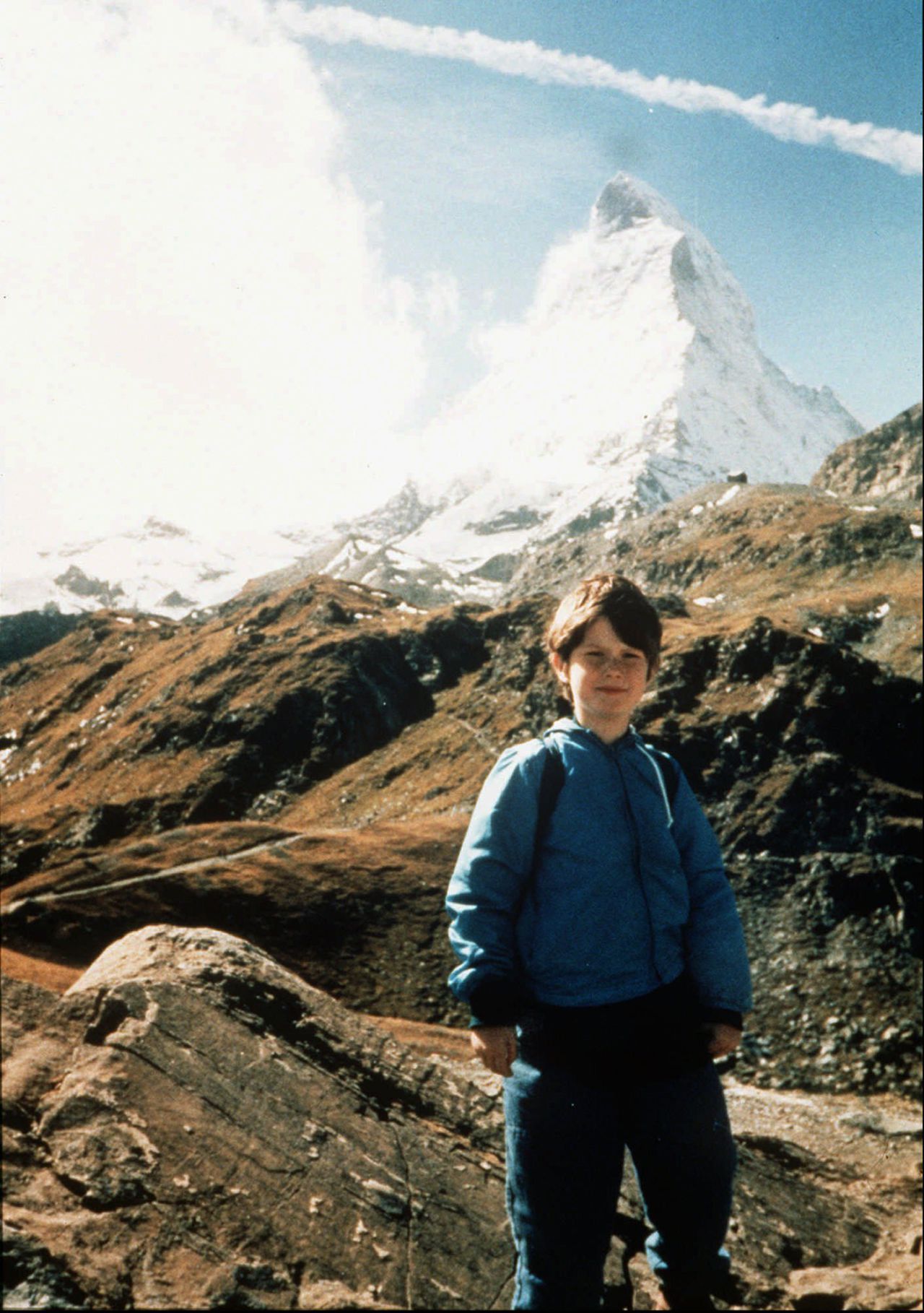

The reader was Reg Green, father of Nicholas, a 7-year-old shot and killed by bandits in a case of mistaken identity during the family’s Italian vacation. Nicholas’ organs were transplanted into seven Italians, and transformed a country’s attitudes about organ donation.

On my blog, I referred to the patient as dying. A reader corrected me. He said that, in fact, the patient was dead.

Green told this story in “The Nicholas Effect,” which became a TV movie (“Nicholas’ Gift”) with Alan Bates and Jamie Lee Curtis. In predominantly Catholic Italy, there was originally resistance to removing Nicholas' life support without a legal process. Until, that is, the Greens argued for donating Nicholas’ organs. I interpreted this to mean that organ donation, in essence, justified allowing Nicholas to die.

Green was kind in correcting me, even complimenting how much I’d gotten right in a complex and cross cultural end-of-life story.

“Just one thing,” he wrote, “Nicholas was dead when we made the decision to donate. His brain had stopped working. The ventilator was keeping the blood flowing and the organs viable but that could have continued only for a short time.”

The distinction matters, especially to a patient’s family, but it is a distinction without real clarity among medical professionals or the people in their care.

The evolving meaning of brain death, and how it shape-shifts across cultures, is the subject of a public forum on April 7 at Harvard Medical School. The forum is not about transplantation, per se, and yet transplantation’s increasing successes, and the attendant need for organs, has long caused brain death to be considered, alongside the more traditional circulatory criteria, as death. The very concept of brain death was born at Harvard in the late 1960s, with transplantation in part the impetus.

In registering for the forum, I thought of Reg Green, but I also thought of Jahi McMath, the teenager who was declared legally dead after a surgical tragedy, but whose parents continue to pray for a miracle. Jahi has been on life support since December 2013.

I serve on the Harvard Community Ethics Committee. Time after time, clinicians and ethicists from Harvard hospitals bring to us concerns about decision-making at the end-of-life. A study of terminal sedation becomes a study of assisted dying becomes a study of transplant listing criteria.

We would tire of it, if it didn’t matter so much.

“Families are not being asked to take someone off life support who is in a coma,” Reg Green reminded me in an email this week. “These people, like Nicholas, are dead: there is no brain telling the heart to pump blood, nothing sending air to the lungs, except the ventilator. And, unless medical opinion is hopelessly wrong, there is no more chance of reversing this than if the heart had stopped beating. Our thought was quite basic: We can’t bring him back. This cannot hurt him. It can help others.”

Earlier this year, the National Health Service in the United Kingdom reported that hundreds of organ donations have been blocked by families of patients who had consented to donation.

Like all ethical problems, there is no clear solution.

Reg Green

It is a point of contention, and of tension, also found in American critical care units, where with some regularity organ procurement officials, advocates for the life potentially saved, are held at bay while the dying become the dead. For organ recipients and grieving families alike, for quite different reasons, every second counts.

Green says some families are simply too distraught. “Saying ‘yes’ means abandoning any hopes of a recovery — and in those circumstances, I’m told, the hospital will eventually agree not to take out the organs. It’s heartbreaking for everyone, of course, and probably condemns someone to death."

“Insisting on legal language to a family that is obviously suffering even more than the average seems cruel,” he added. “There is also a practical consideration: the publicity connected with such a dispute is likely to give both the hospital and organ donation as a whole a bad name, possibly deterring potential donors. Still, since these are a … small percentage, it seems to me worth foregoing the organs.”

And then, with his unique understanding, Reg Green pointed out: “Like all ethical problems, there is no clear solution.”

UPDATED, April 4, 2016

A message from Reg Green:

I am the father of the 7-year old boy, Nicholas Green, mentioned above whose organs and corneas my wife and I donated in Italy. I would like to clarify something. There was no resistance to the decision from either the health care professionals or the public. The whole country seemed want to say "thank you," including the president and prime minister — both of whom asked us to visit them and talked to us like friends or family rather than leaders of a country. Pope John Paul II who was so touched by the tragedy and Italy’s warm-hearted response that he authorized a magnificent bell to be made with Nicholas’ name and that of his seven recipients on it, even kindergartners who knew nothing about organ donation but understood that a little boy had saved other children, and more than a hundred towns all over Italy who have named schools, streets, squares and parks — and a bridge — for him. Catholicism is not the problem. After all, Spain has the world’s highest organ donation rate. The problem is that the subject of organ donation is too remote for people to think about. In developed countries, when asked, 90 percent of people say they favor organ donation. But when they arrive at the hospital to find someone they love is brain dead, however, the shock is often too much for them to remember what it means to the people dying on the waiting list. They say "no' and a few days later realize they have missed the best opportunity they are ever likely to have to make the world a better place. The solution is to think of it ahead of time as I hope everyone reading Paul McLean’s essay will. Our own website would be one place to start.

-- Reg Green

This article was originally published on March 31, 2016.