Advertisement

Russell Banks On Travel, Writing Everything Down, And That Time With Fidel Castro

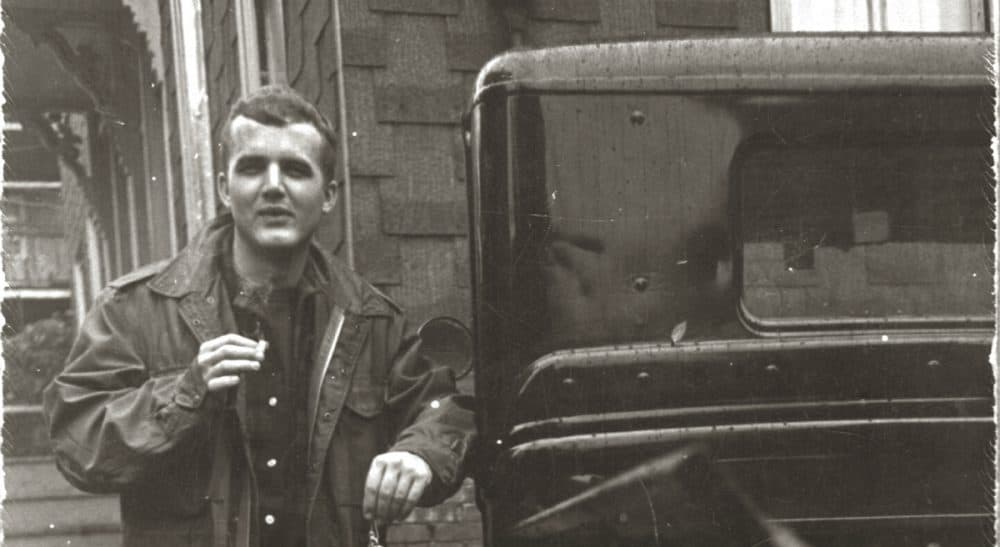

To read Russell Banks is to spend time with a writer who carries in his bones a New England of faded mill towns and fragmented lives. Twice shortlisted for the Pulitzer Prize in fiction, Banks was born in Newton, Massachusetts, raised in small town New Hampshire, and wrote his first short stories in Boston in the early 1960s.

But it is the far-flung reaches of the globe — as well as the deep, hidden interiors of the author's own emotional landscape — to which we are transported in the 10 essays in "Voyager," Banks's new collection of travel writings. Themes familiar from Banks's fiction are here — there is wanderlust and moral ambiguity, the stain of slavery and the grapplings of a good man recalling some bad choices. And there is the writing we've come to recognize: arresting, beguiling, direct. Who wouldn't want to read a book that begins, "A man who has been married four times has a lot of explaining to do."

I spoke with Russell Banks recently by phone. Our conversation, slightly edited and condensed for clarity below, ranged from the author's recollections of being hosted by Fidel Castro, to the guilty reading pleasures on his bedside table. — Kelly Horan

You write in "Voyager" that a memoir is like a travel book — structured as much by what it leaves out as what it puts in. What you put in to the 10 essays in this collection covers not only the essence and history of place, but a good deal of your own private geography, as well. Is there something about travel that makes you especially introspective?

I think that’s true, at least for me. Once I’m on the move and out of my familiar environment -- meaning the one I can live in without thinking much about it, where my moves are more or less automatic — once I’m in a world where I essentially have to invent my moves on a moment to moment basis, I become more reflective and conscious of my past and the need to address it and put it into some kind of coherent narrative for myself.

I keep a little notebook, like most writers do, in my pocket. When I am traveling, I write everything down. The notebook fills very quickly with the names of trees, the weather, an idle conversation with someone in the seat next to me on the bus. It also fills with memories and speculations and remorse and so forth going back in my own life. There is something about casting myself loose that opens me up to where I am, but also to where I am in my own life, as well.

You once told an interviewer, “The narrative that early on attracted me was the run from civilization, in which a young fellow in tweeds at Colgate University lights out and becomes a robin hood figure in fatigues in the Caribbean jungle.” You did that — fled Colgate in dark of night after only eight weeks as a student there. You didn't quite make it to the revolution, but 42 years later, you were Fidel Castro's guest in Havana. What place does Cuba have in your heart?

I live half the year in Miami, so [Cuba] is easy access for me. I went down in December for a week just to hang out, with no official reason for being there. I just wanted to catch the flavor of it and compare it to the last time I was there, in 2003, with Bill Kennedy.

The difference was amazing to me. It’s not that surprising when you think about it. In 2003, there was pessimism and bleakness on the street – bitterness, even. This time, there was enthusiasm, openness, energy and optimism. It went from pessimism to optimism in just a few years, and that has everything to do with the American opening and end of the embargo.

Streets that in 2003 were all boarded up – I'm talking about every doorway – were open now. In every doorway, people were selling t-shirts, food, drink, sandals. Every door that, 12 years previously, was boarded up and empty. It’s a fantastic shift.

A fantastic shift, but do you fear for Cuba? A theme in your title essay, "Voyager," is the tragedy of seeing these Caribbean islands that you love so much loved to death by tourism. Do you worry that the terrible dilemma facing the people who live there – having to exploit their home to feed their families — will be Cuba's dilemma now, too?

I have deep anxiety over it. Just before I left Miami to come back north [this spring], the first cruise ship from the U.S. touched down in Havana and circumnavigated the island with 1,500 American tourists on board. I thought, Oh boy here they come. What is going to happen to this island? Instead of 300,000 academics, ornithologists, journalists and others there for professional reasons, they are replaced by 5 million American tourists coming in for a holiday where they want, essentially, to buy the place on some level. American real estate and banking and manufacturing interests are busily lining up to serve those interests. Not to mention the tourist industry.

...the first cruise ship from the U.S. touched down in Havana and circumnavigated the island with 1,500 American tourists on board. I thought, <em>Oh boy here they come</em>. <em>What is going to happen to this island?</em>

Russell Banks

I did ask Fidel about that in 2003. What happens when the embargo goes down? He said at the time that he thought the revolution had settled into the Cuban people and culture like DNA, and they could resist all the temptations and the blandishments. But it was clear on [my most recent] visit that they are embracing capitalism with a fervor that is scary. I would hate to see in Cuba what happened in the Soviet Union after the end of the USSR. A better model might be Vietnam, where you have a Socialist state side by side with a capitalist economy. It’s really going to be a touch and go situation for a decade. And it’s not reversible. It doesn’t matter who becomes president here or who replaces Fidel.

It’s really almost tragic, because, to survive, you have to almost devour yourself, or to allow yourself to be devoured. That’s the tragic paradox of life in that part of the world. It’s history, too. History is so profoundly corrupted by colonialism and slavery that getting out from under that shadow is very difficult. It doesn't matter if the government is of the left or the right. Look at Venezuela, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Haiti. It’s still somehow crawling out from under the weight of 300-400 years of dominance by colonialists and empire and slavery. It’s not something where you say, “Let’s start over again.” It’s the shadow you carry deep in the culture for hundreds of years. Even today in the U.S. we are dealing with the residue and aftermath of 300 years of slavery and racism.

Advertisement

With regard to Cuba, sitting for six hours with Castro, I asked him, “Is there anything you regret?” He did say he regretted having trusted the Russians. I thought that was funny at that point. The other thing he said is that he thought the revolution would eliminate racism, but he said, “Look. Everyone in a position of servitude and at the bottom is black, and everyone in power looks like me, is white. It's there in every respect, and it makes this country extremely vulnerable to exploitation by tourism.”

You mentioned racism in the U.S., and I'm reminded of what you said once about “the old American weave of violence, politics, religion, race.” What do you make of the current political moment and the race for president?

I was pretty confident in my observations earlier this year — and many pundits in the news media were, too — thinking that Bernie Sanders or Donald Trump had no chance to last beyond [last] July or August. Here we are in the following May, and both Sanders and Trump are tapping into something that people didn't realize was there – profound anger and dissatisfaction with how political life in America has operated for the last half century.

With Trump, that anger takes one form, and it's another form with Sanders. With Trump, it’s mostly a racist and nativistic form, and with Sanders, it takes a more radical leftist, Socialist form. In both cases, they are dealing with populist anger, and they are being carried on a wave of it, tapping into it. I for one didn't realize it was there.

The most interesting political moment of my lifetime right now, in the U.S., is what is happening here in terms of domestic politics. What unfolds over the next six month is very telling and will reveal a great deal about what will happen in next 25 years. I am waiting with baited breath, anxiety and excitement and interest at the same time. I can't say I anticipated it.

I occasionally write for Libération and Le Monde, and they think I am very smart [in France] because I predicted in 2006 that Obama would be our first black president. They thought I was prescient. I wrote through the fall and winter about the American political scene for these magazines. I predicted Hillary’s takeover of conventional moderate to conservative republicans, and I predicted that there would not be much difference between the two as the campaigns unfolded. I was wrong, wrong, wrong.

We can’t start over again. Our fantasies and dreams have to be accommodated to inescapable reality.

Russell Banks

I read somewhere that you said that any book, when it is first published, is forced to fit into the gestalt of the moment. What is the gestalt of the moment? Where and how will your "Voyager" fit into it?

It’s very hard to know. With fiction, novels and short stories, at this point in my career, I can kind of anticipate how it’s received. I know when I have written something that seems controversial that it will be received with difficulty, restraint or enthusiasm. With this book, I can’t predict anything. I haven't any idea how it will resonate out there in the world. I do think this though, that it's a book about a man in his 70s looking back over his life, which includes the '50s and '60s and on, which has got to be true for every Baby Boomer in America. Especially men. We are the generation whose childhoods were in the 1950s and adolescences in the 1960s, and now we are in our 70s, and we can’t help but be aware of our mortality, and we can’t help but look back over our lives — our options are so diminished and limited. We can’t start over again. Our fantasies and dreams have to be accommodated to inescapable reality. We have that growing awareness of age and mortality and the past and the importance of the past and the historical past. I hope that is how it will be read. That would be satisfying to me.

You have likened travel books and memoirs to guilty pleasures. Now that you've written one, do you still?

Travel books still engage me. When I say guilty pleasure – when I say travel books, I’m talking about guidebooks, not Paul Theroux. I’m talking a Lonely Planet guide to Ecuador. They are fantasy trips for me. It’s fantasy travel. You read the list of hotels in the Fodor’s and think, I wouldn’t mind staying there. It’s something that people who like sci-fi or fantasy experience – it is that it takes them out of their life in a harmless and unchallenging way, and it’s an interlude and a restful one, and I read them with that in mind.

Russell Banks is the author of more than a dozen novels and collections of short stories, including "Affliction," "The Sweet Hereafter," "Continental Drift," "Cloudsplitter" and "Rule of the Bone." He is a past president of the International Parliament of Writers and a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. His work has been translated into 20 languages and has received numerous prizes and awards, including the Common Wealth Award for Literature. He lives in upstate New York and Miami, Florida.

You can read an excerpt of "Voyager" here.

(Excerpt Copyright © 2016 by Russell Banks. Reprinted courtesy of Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.)

Readers! Ask Russell Banks questions of your own! Banks will read from and discuss "Voyager" at Harvard Square Books on Monday, June 6.