Advertisement

Reporter's Notebook: Covering Muhammad Ali When He Was King

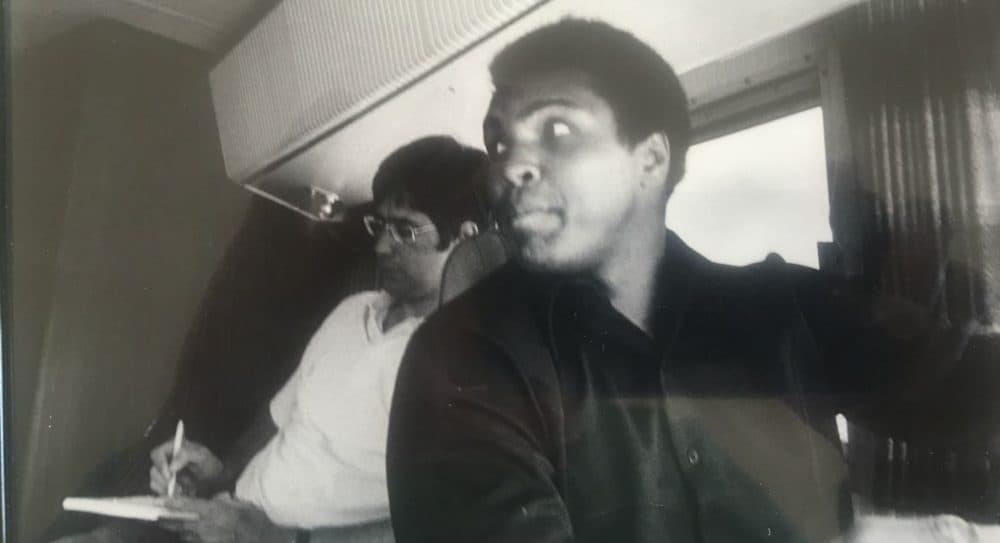

The photograph shows a handsome black man — he often mockingly described himself as “pretty” (and he was) — behind the wheel of an interstate bus that had been converted into a mobile hotel. It was the summer of 1974, and I had been with Muhammad Ali for the better part of a week, tagging along with him nearly everywhere. He was driving the bus to the repair shop several miles away when the picture was snapped.

For days he had pressed fractured poetry ("You think the world was shocked when Nixon resigned?/Wait `til I whup George Foreman's behind./Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee./His hand can't hit what his eyes can't see.") on me, the skeptical young staff writer from People Magazine seated directly behind him.

He had also ladled windy incantations (“I am the greatest”) with inconsistent religious beliefs, too (“whites are devils”), and a corollary: a gigantic spaceship filled with the “colored” people of the world would return to destroy white people.

Co Rentmeester, the photographer, pressed into the windshield to get a better angle on the driver of the bus that was hurtling down the interstate. Co was shooting away when I gathered up the nerve and asked, “So how can a man who preaches world brotherhood rationalize support for such patently racist teachings?”

Co was shooting away when I gathered up the nerve and asked, 'So how can a man who preaches world brotherhood rationalize support for such patently racist teachings?'

As Ali turned to glare at me like only a heavyweight boxing champion could, he pulled the steering wheel. Regaining control of the careening bus, eyes riveted on the road, he reminded me that if we had all been killed then the newspaper headline would read “Muhammad Ali, The Greatest, Killed With Two Others In Horrific Bus Rollover.”

And, then he winked.

The mouthy 19-year-old, Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr. from Louisville, Kentucky, mounted the world stage in 1960 when he won the gold medal in boxing at the Olympic Games in Rome. Four years later, at age 22, he won the world heavyweight championship in an upset victory over Sonny Liston. He exited the stage last week when he finally succumbed, at age 74, to the blows his head and body had absorbed from the fists of sluggers like Liston, Ken Norton, Joe Frazier, George Foreman, Leon Spinks and even the genial “Bayonne Bleeder,” Chuck Wepner.

As a young man, Clay reveled in “The Louisville Lip” nickname bestowed on him by the then less than worshipful news media. Many journalists turned even more disparaging when he converted to Islam, forsook his Christian name for Muhammad Ali, refused to subject himself to the draft and, as a result, was convicted of draft evasion in 1968, which led to a ban from boxing and forfeiture of the heavyweight boxing title.

Advertisement

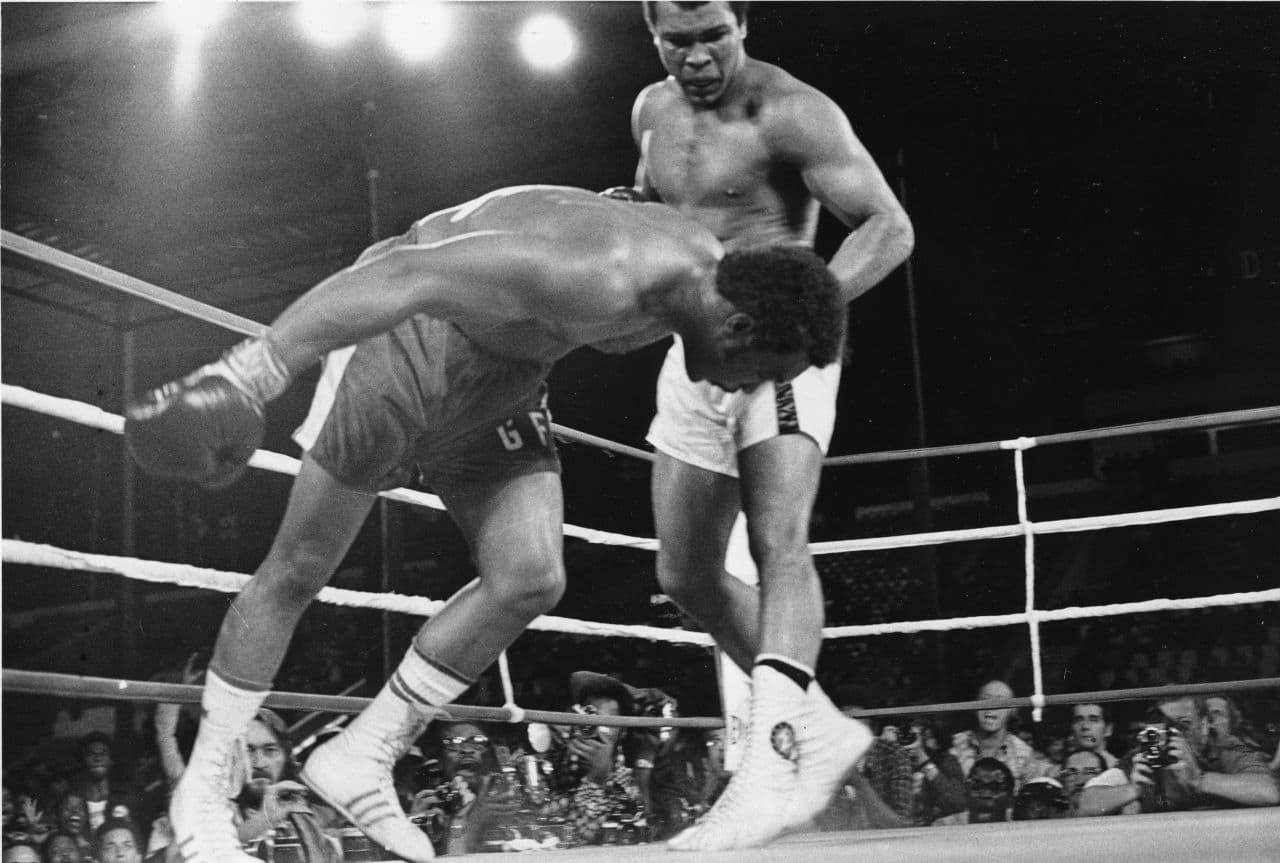

By 1974 when I caught up with him for a week of in person interviews and observation, the conviction had been overturned and he was on the road to reclaiming what was rightfully his, even though his chances were negligible against reigning world champion Foreman in an October championship bout in Kinshasa, Zaire dubbed “The Rumble in The Jungle.”

Over the summer of that year, Ali withdrew to the log cabin training enclave in Deer Lake, Pennsylvania. Hours before sunrise, his body would be lathered in Vaseline, presumably to make him perspire more on daily jog. Wearing army surplus combat boots and gray sweats, he lumbered through the pre-dawn mist down narrow and winding country roads, the van carrying his trainers illuminating the pavement ahead and protecting from behind. Hours later, he would rhythmically beat the speed bag like an accomplished drummer, sweat beading on his brow and bare chest, preening for tourists’ and flirting with pretty girls.

Even then his loyal personal physician, Ferdie Pacheco, was concerned the fight game was sucking the juice out of the body he considered to be the most perfect he'd ever seen. Pacheco argued that win or lose, the fight in Kinshasa should be Ali’s last, even though Ali himself was already talking about a series of easy subsequent fights “for the money.”

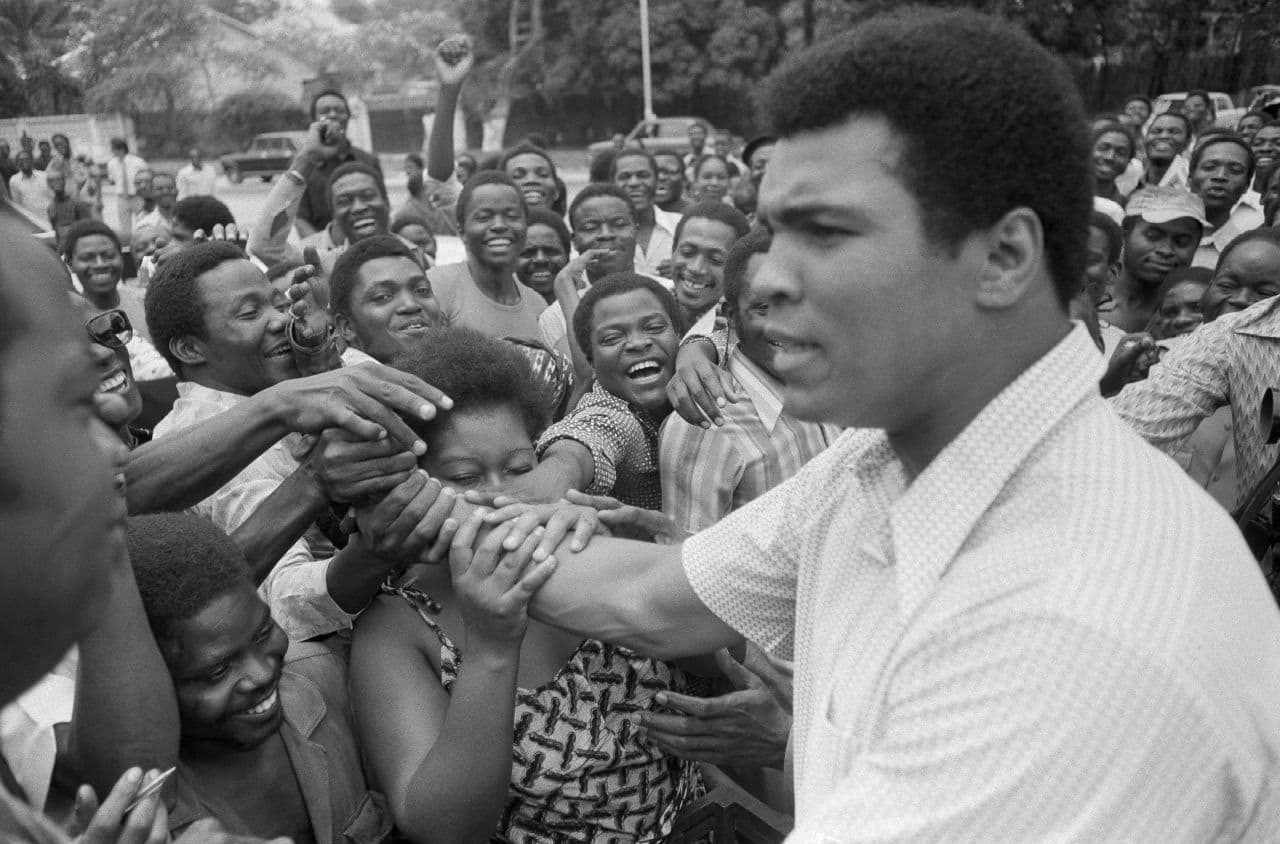

In Zaire, he out-maneuvered the stronger and younger Foreman. The stunning eighth round knockout captured the imaginations of even former skeptics like me. As he had forecast months earlier, his name and the Lingala chant Ali Bomaye ("Ali Kill Him") was recognized by people from Zaire to The Philippines, the site of his next fight — “The Thrilla In Manilla” — against Joe Frazier.

Later in 1974, Rentmeester and I caught up with Ali again at a mosque in Chicago’s notoriously perilous South Side (only a bribe persuaded the cabbie to take us all the way there). When we arrived, Ali’s children were sleeping soundly in the back seat of an idling Rolls Royce, unattended at the curb.

Then it was off to his mother-in-law’s suburban home where a television embedded high on the mirrored living room wall was broadcasting “The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman.” A young man from Zaire, who had returned home with the champ, cried as the pursuers of the fleeing slaves in the movie torched the barn where runaways had sought shelter. “Why?” the young man wailed.

Ali, buried beneath the two young daughters on his lap, seemed about to comment when someone angrily muttered, “White men. That’s what they do.”

Loosening his arm lock on one daughter, Ali corrected: “Some white men, not ones like him.” He gestured toward me.

And, then he winked.