Advertisement

The Most Important Moment For Civil Rights This Century Is Upon Us

Students of racial violence in the United States identify three discrete periods of such terror after slavery: the era of the noose from 1890 to 1930; the Jim Crow/Civil Rights years; and the current experience of mass incarceration. Police brutality — now more visible than ever, more disruptive of the post-racial fiction than any other data point, and, after last week, a more powerful tutorial on the costs of gun glorification than a congressional sit-in — is the constant across all these decades.

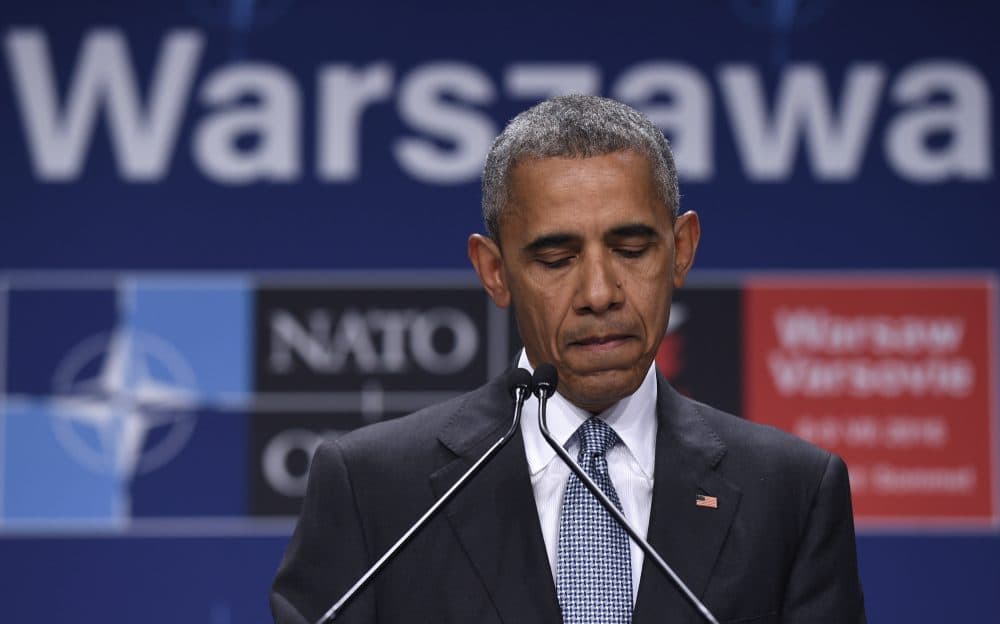

But today it may also provide a tipping point on the dark landscape of racial deaths. There is light out there to be grasped — and brightened — by all to whom President Obama spoke from his makeshift White House in Warsaw last week. We are on a fault-line. But with the right choices, we can recast a future that today must seem grim to the children of Alton Sterling and Diamond Reynolds.

The street actions are as much about demonstrating what a Great America looks like as they are about the demand for one.

The Washington Post reports that there have been 491 fatal police shootings so far this year. While it is important to note the similarity of narratives of police-involved homicides over generations and to maintain the count, it is equally vital to pay heed to what is different today, for there is no other way of marking the progress of what is, to date, the most impactful civil rights movement of the century. Ferguson set the table on two fronts: It broke the pattern of federal stand-offishness, and it revived the practice of assemblage and civil disobedience.

As to the first sea change: Until 1965, when Assistant Attorney General John Doar took on the Mississippi Burning case, the Department of Justice mostly stood to the side and allowed local authorities to investigate police homicides with no federal oversight. Non-intervention remained the general policy until Congress passed a law 22 years ago authorizing federal officials to conduct comprehensive investigations of local departments. Whether the Obama administration will undertake a system-wide investigation in Baton Rouge, as it has done in Ferguson, Cleveland, Chicago and North Charleston is not yet clear. Certainly it would be warranted given the distressing history of abuse by Baton Rouge police officers.

In 2005, when state troopers from New Mexico and Michigan came to Baton Rouge to assist evacuees after Katrina, they were so alarmed by the racist behavior of the local officers that they documented and reported what they saw and heard. Just three months ago, a video showing a high school sophomore being repeatedly struck by a Baton Rouge sergeant made the rounds. And a 2014 report revealed that of the 35 use-of-force complaints that year, the department’s internal reviewers sustained not one. Whether or not her attorneys intend to pry into this tiresome history, Attorney General Loretta Lynch’s announcement that she is launching an immediate investigation of the Alton Sterling shooting appears now to be required protocol, owing to the Black Lives Matter movement. Most likely more will be necessary, and public support for such an effort must be solid and enduring. Critics have noted that under President Obama, the Justice Department has explored the outer reaches of its power to restructure and re-train police departments, local authorities have successfully resisted federal directives, and Washington has too often dropped the ball.

On the matter of what the Founding Fathers termed “peaceable assembly,” here, too, Ferguson broke with the past. Today it takes about four hours — coincidentally, the amount of time Michael Brown’s corpse lay in a street in August 2014 — to fill an American downtown with the creative disorder of demonstrators. These will never be serene moments of prayer and peace, much as mayors and governors might like that. But neither should they be confused with the urban riots of yore. Coming together to democratize our country, in the old-fashioned way of Stonewall, is a cross-generational, cross-class, cross-gender identity movement that is at once aggressive, insistent, democratic and destiny-driven. To be sure, there are tactical differences, generational distinctions, racial frameworks and a range of comfort zones, but the unifying theme is that law enforcement cannot damage communities of color and withdraw without eliciting sustained attention. The street actions are as much about demonstrating what a Great America looks like as they are about the demand for one.

Orlando, Baton Rouge, St. Paul and Dallas, while different from each other, are connected by the uniquely American fault-lines of hatred and firearms.

What should also go without saying is that there is a vast moral, not to mention legal, distinction between confrontational action (not everyone’s cup of tea) and shooting down police officers. Orlando, Baton Rouge, St. Paul and Dallas, while different from each other, are connected by the uniquely American fault-lines of hatred and firearms. We will one day look back on this past week — as we have with Selma — and measure our government’s response to the chaos. If the right choices are made, we may be able to say, as Martin Luther King, Jr. once did, we emerged from chaos to community.