Advertisement

Commentary

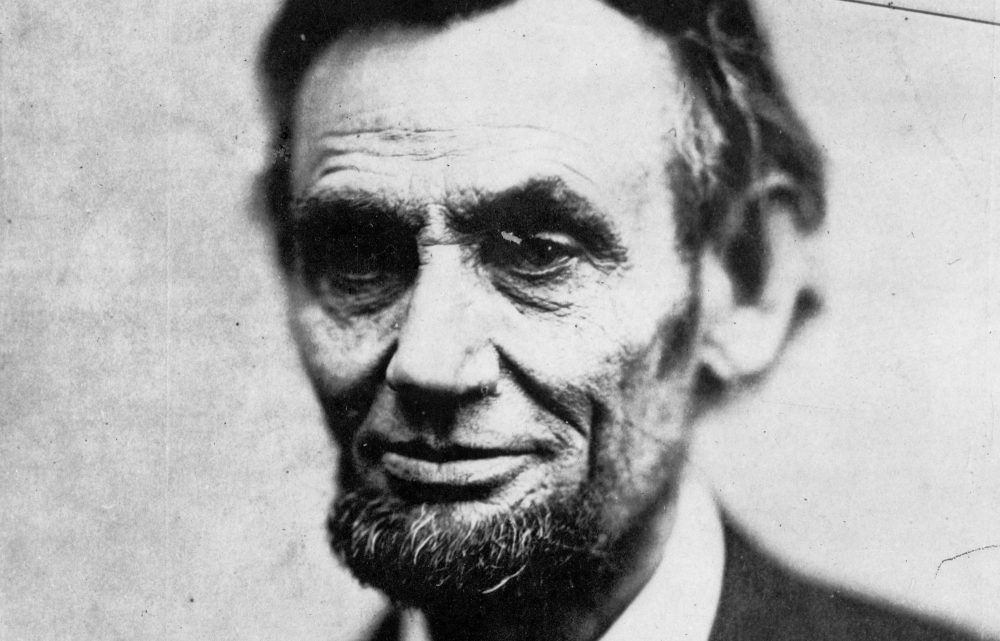

Echoes Of 1863: How Lincoln Transformed Thanksgiving, And Why It's Relevant Today

Thanksgiving, 1863. It was the height of the Civil War. Over 100,000 soldiers would die that year, fighting their fellow Americans over, primarily, slavery. By the time the War was finished in 1865, over 620,000 Americans would be killed — more than World War I, World War II, and the Vietnam War, combined.

It was in the midst of that gruesome domestic conflict that President Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation for a day of national Thanksgiving. We’ve celebrated as a nation, together, the fourth Thursday of November ever since.

Written by then-Secretary of State William H. Seward, the Thanksgiving Proclamation reads more like a prayer than a government document: The blessings in the United States, Seward wrote, should be “solemnly, reverently, and gratefully acknowledged, as with one heart and one voice, by the whole American people.”

With Civil War raging and the nation sharply divided, Seward’s proclamation was a call for unity. Thanks, he wrote, should be given that despite the severity of our War, peace had been preserved with all other nations. And despite its magnitude, the War had not stopped our nation’s flourishing industry.

Today, as our country struggles with its new president and with itself, we might be wise to ask, what are we thankful for, as a nation?

Together, we had much to be grateful for, and more importantly, something to look forward to: We should expect as a nation, he wrote, to experience years of “large increase of freedom.”

Today, as our country struggles with its new president and with itself, we might be wise to ask, what are we thankful for, as a nation? Are we still expecting that large increase in freedom?

When was the last time we came together and gave an open appreciation for the good that is in, and born of, our country?

Rather, the bubbles of our regions, and our communities, segregate us. We see an institute of higher education, Hampshire College, refuse to fly the American flag.

But our flag, like our country, needs those who believe in peace, diversity, and unity to fly it proudly, that its status as a beacon of hope and opportunity not inadvertently become a symbol of our nation’s darkest demons. It requires that we preserve our better angels, and give thanks for our lighter side when faced with our dark hour, as we did 153 years ago.

Advertisement

For our nation does have its demons; we do have unhealed wounds, picked open with every police shooting of an unarmed black child, infected with every crime of violence against our brothers and sisters from other motherlands, and stinging in pain at every mindless remark made by out-of-touch leaders across the political landscape.

Seward’s proclamation asks us to pray for “the Almighty hand to heal the wounds of the nation and to restore it, as soon as may be consistent with the divine purposes, to the full enjoyment of peace, harmony, tranquility, and union.”

How, then, do we heal our scars as a nation?

We must reach high, and we must lend our hands to help lift our neighbors with us. We must build up; we must strive for justice and truth. We must refuse to permit the weed of hatred to choke off our nation — and our selves.

We must listen to each other and strive for compassion.

Which means, in the midst of our civil strife, we must reach across the table and break bread with our fellow Americans, in the heartland, and in the South. We must extend our hands and open our hearts to one another, from New England to the South West, Texas to Minnesota, Hawaii to Maine, Florida to Alaska.

...when we give thanks, as Lincoln and Seward asked, we may offer it with, as Seward wrote, "humble penitence for our national perverseness and disobedience.”

We must find that place, within our selves, that knows we are a nation that has accomplished great things — and that has more greatness yet to achieve: Justice, equality, opportunity, the pursuit of happiness. Freedom. The United States of America has persevered and thrived throughout the conflicts of our history, always striving to rise higher. We have since our very founding as a nation expanded and secured liberty and equality far beyond what was once considered sufficient.

And our job is not done.

But for the progress we have made, we can and should give thanks. Together.

And when we give thanks, as Lincoln and Seward asked, we may offer it with, as Seward wrote, "humble penitence for our national perverseness and disobedience.”

And then, with full bellies, we must get to work, preserving our nation’s unity and lifting it to a new level of liberty, and justice, for all.