Advertisement

Little Word, Big Debate: NPR, And Whether To Call A Falsehood A Lie

COMMENTARY

I am a writer, journalist and frequent contributor of opinion essays to this affiliate of NPR, the venerable news agency that announced Wednesday that it will not label the president’s false claims a lie. Perhaps it is a well-meaning attempt to preempt accusations of libel against reporters, or head off the loss of federal funds. Maybe it is an attempt to preserve the civilized and reasonable tone that makes NPR a source of news I have come to trust. No matter; it won’t work.

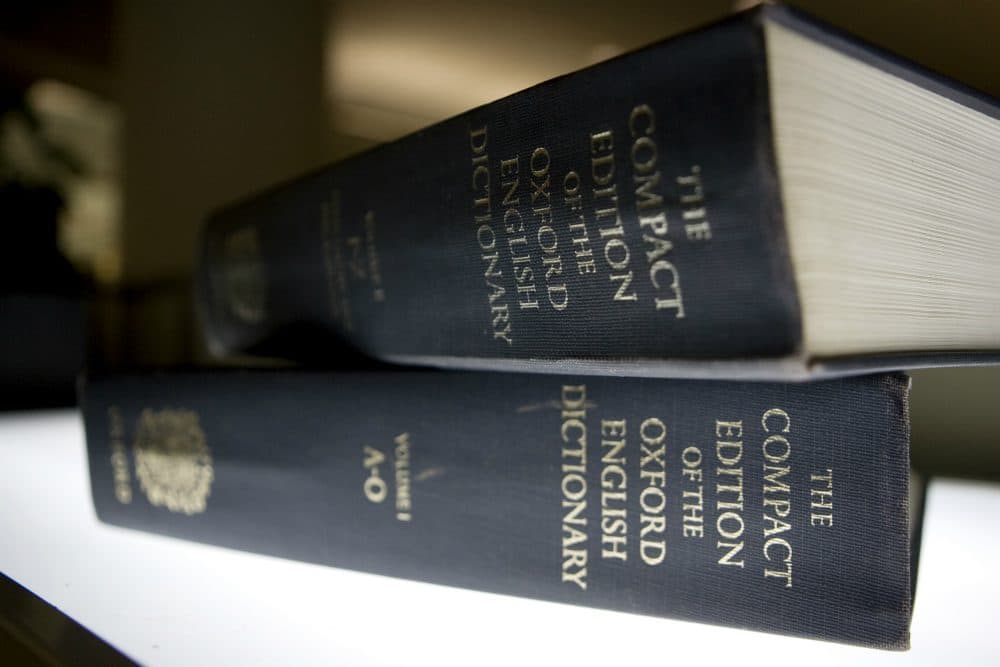

On NPR’s "Morning Edition," reporter Mary Louise Kelly explained that, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, a lie is "a false statement made with intent to deceive." Reporters have to be able to prove that intent, said Kelly, and if they cannot, NPR will not label a falsehood a lie.

"Without the ability to peer into Donald Trump's head, I can't tell you what his intent was. I can tell you what he said and how that squares, or doesn't, with facts."

Mary Louise Kelly

"Intent being the key word there," Kelly said. "Without the ability to peer into Donald Trump's head, I can't tell you what his intent was. I can tell you what he said and how that squares, or doesn't, with facts."

So NPR turns to the dictionary for cover, pointing out that journalists are not psychologists. Fair enough. They're not. But in its bid for objectivity and fairness, NPR seems to be ceding too much ground to a serial dispenser of untruths, a man who campaigned on falsehoods and hyperbolic broadsides — "Mexicans are rapists" — and who, just this week, revived his own lie that there was widespread voter fraud in November. (Side note: That this charge calls into question the validity of his own victory seems lost on the president.) So, NPR reporters will lay out the facts, and they will not label Trump's untruths lies.

This approach is careful — lie is a very big little word, and, as Dan Barry points out in his excellent analysis of this question in The New York Times, "Words matter." But NPR's kid gloves approach is lacking. Public figures — journalists and presidents alike — have a platform and a reach that regular people do not have. Their words carry weight, and they reach many. When the president repeats a false claim, and when the press repeats it, the press becomes complicit in spreading the lie by unwittingly offering that claim credence.

Advertisement

With all due respect to Kelly and NPR, lying, as recent Times headlines that use the three-letter word have demonstrated, is an all or nothing proposition. That is, a lie is either a lie, or it's not. Ditto the truth. A statement can't be both. And if the press lets a lie take hold, it risks setting into motion a series of real events with actual consequences based entirely on something that isn’t true. Witness: the invasion of Iraq, which was predicated on the lie that Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction.

When New York Times reporter Judith Miller uncritically reported the Bush administration and Ahmed Chalabi's line on Hussein's possession of WMDs, she helped legitimize the fallacious claims. Miller may not have believed that she was lying to the public, she may well have been too credulous, but the effect of her articles on the subject of Hussein and WMDs is rightly regarded as one of the lies that got us into the war, the ongoing effects of which have been catastrophic to both American and Iraqi lives.

Similarly, Trump's fallacious assertion of voter fraud has escalated into a tweeted pledge to conduct an actual investigation. The outcomes of an investigation predicated on a lie could have a real effect -- namely, more favorable treatment of states that swung red in November, as Trump promised in his Jan. 11 press conference, and punitive measures against states that didn't.

"...if all others accepted the lie which the Party imposed—if all records told the same tale—then the lie passed into history and became truth."

George Orwell, 1984

By favoring “unsubstantiated” over "lie," NPR accepts a premise that undermines its own responsibility to report the truth. Unsubstantiated suggests that something still has a chance of being proven true. With the president’s lies, this is not the case.

In his dystopian vision of a totalitarian future, "1984," George Orwell wrote, "...if all others accepted the lie which the Party imposed—if all records told the same tale—then the lie passed into history and became truth." NPR's decision not to label a false statement a lie effectively gives Trump the power to pass a lie into history and wait for it to become the truth.