Advertisement

Commentary

Funding The NEA Ensures Art Is Not Just For 'Rich, Liberal Elites'

Last month, conservatives attacked National Endowment for the Arts funding as welfare for rich liberal elites. Even though this idea is demonstratively false, I understand why that concept might resonate for many. Given how expensive participation can be — from buying tickets to performances to getting an arts education to pursue a career — there’s an uncomfortable truth in the idea that arts and culture is for those at the top.

This is certainly true in the literary world. As a former literary agent, I can attest that having a Masters of Fine Arts degree gives writers a leg up in getting published. It’s no guarantee of success, of course, but an MFA degree quickly signals to industry gatekeepers a certain level of seriousness and polish. Moreover, a writer with an MFA will most often have better industry connections than one who does not, unless he or she is lucky enough to be connected through family networks.

Given how expensive participation can be ... there’s an uncomfortable truth in the idea that arts and culture is for those at the top.

According to a recent Association of Writers & Writing Programs survey, it costs roughly $30,000 in tuition and fees (not including the cost of living) at a public university to get an MFA. While 54 of the country’s best programs have moved in recent years toward offering tuition waivers and stipends for all admitted students, the cost of the majority of programs remains out of reach for many. Moreover, the programs offering a completely free ride have average admission rates of about 2.5 percent.

Over 20 years ago, I was awarded a teaching fellowship to Boston University’s Creative Writing program, which allowed me to graduate with manageable debt of about $7,000. With a friend, I started teaching writing workshops in Brookline under the name GrubStreet Writers. Our aim was to bring the rigor of the university out into the community. We worked with anyone who signed up — students, lawyers, copy editors, cab drivers. We launched with eight students, but quickly grew, and today we teach over 3,000 students per year.

Despite the fact that we don’t have admissions standards, a huge number of our students have published books, essays and poems; they’ve won awards, attended graduate school, started publishing imprints and more. Our belief proved true: People of all ages and backgrounds have important stories to tell and a deep desire to work hard to tell them and tell them well.

Founding GrubStreet has taught me that what emerging writers need most is not motivation but access — access to a welcoming and rigorous arts education that doesn’t have prohibitive admissions standards and one that doesn’t require students to take out crushing bank loans or leave their full-time work. These barriers are too high to scale for most older students with family obligations or students from low- and middle-income backgrounds.

NEA-supported, community-based organizations like GrubStreet and others such as The Loft Literary Center in Minneapolis, Lighthouse Writers Workshop in Denver and Hugo House in Seattle provide powerful alternatives to traditional and narrow pathways to publication. They hold the promise of helping democratize the writing field, a field that remains stubbornly white. Data from the Cooperative Children’s Book Center show that the number of diverse books published each year has hovered at around 10 percent for more than 20 years. In order for books to be relevant, they need to reflect the world as it is today in all its complexity and richness.

To do that, we need to nurture all voices by leveling the playing field, and the NEA’s role in this effort is crucial. President Trump's budget proposal would entirely eliminate funding for the NEA. But its support helps organizations across the country remove financial and cultural barriers to the arts for writers of all backgrounds, experience levels and income brackets.

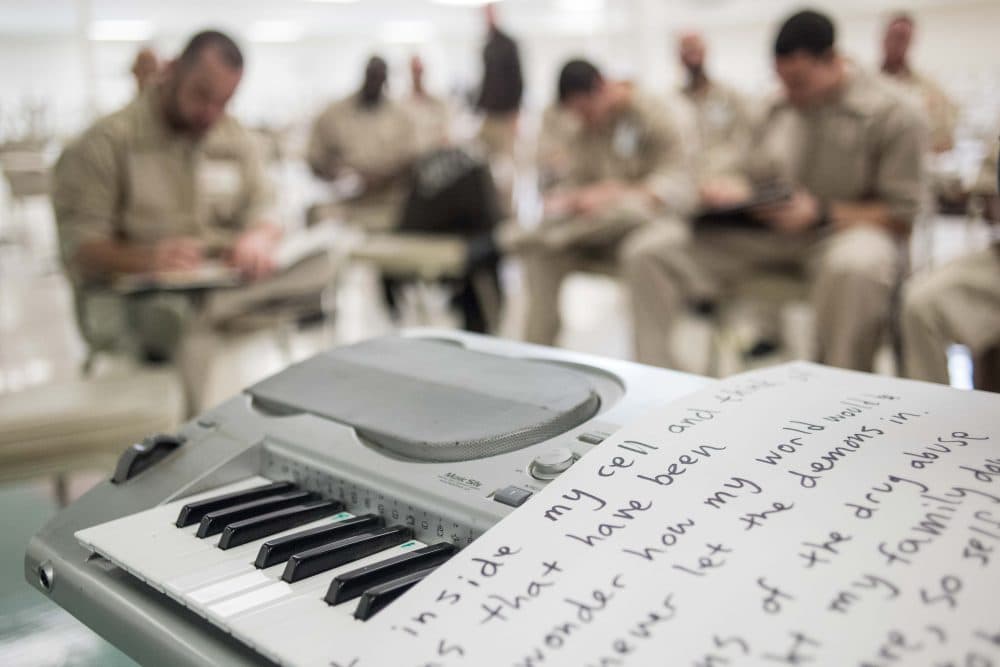

A tiny sampling of what the NEA will fund: writing workshops in an outpatient treatment center and in a low security prison with People & Stories / Gente y Cuentos; events and an online conference featuring Asian-American talent put on by the Asian American Writers' Workshop and sign language interpretation for the Sunken Garden Poetry Festival at the Hill-Stead Museum.

So I agree with this aspect of the conservative commentary: The arts shouldn’t be exclusively for the elite. But they’re wrong about the NEA. NEA and public funding help make the arts accessible to all.

[The NEA] helps organizations across the country remove financial and cultural barriers to the arts for writers of all backgrounds, experience levels and income brackets.

That said, if my conservative friends still aren’t convinced, here’s an argument they have to love: Keeping the NEA is good for employment. A report released last week by the NEA and the Bureau of Economic Analysis found that here in Massachusetts, 3.6 percent of the state's employment are jobs where the workers are engaged in the production of arts and culture goods and services. And nationally, the arts and cultural sector contributed almost $730 billion to the United States economy in 2014; the NEA’s annual budget is $148 million.

In truth, the NEA is good for our culture and for our economy. So let’s add new meaning to Mark Twain’s great line: "Truth is the most valuable thing we have. Let us economize it."