Advertisement

Commentary

After New Orleans Removes Statue Of Robert E. Lee, Reckoning With Boston’s Slave History

The stony quartet of those contemptuous Confederate cenotaphs that once characterized the soulful streets of the Crescent City sing no longer against its blue winds.

After two years of debate in its city council, the City of New Orleans last week removed the last of four monuments erected in the decades after the Civil War.

The memorials to Confederate leadership were sitting on public lands and for decades convinced denizens of that city to believe in their odious American prevarications: the lie that blacks are inferior to whites, the canard that the victimhood of the South was because of illegitimate Northern aggression, the sham that segregation is part of the natural human order and that miscegenation is a sin.

The last statute to be removed bore the likeness of Robert E. Lee, the infamous Confederate general whose chiseled image was positioned northward to express his perpetual defiance of the anti-slavery states. Weeks earlier, the sculpture of Jefferson Davis, the Confederacy’s president, had been taken away in the municipal haul, followed by Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard. A marble obelisk championing white supremacy was also removed this spring.

New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu defends the removal of these statutes as a form of civic cleansing, a public purging necessary for his city to apologize and grow from its past.

“These statues are not just stone and metal. They are not just innocent remembrances of a benign history. These monuments purposefully celebrate a fictional, sanitized Confederacy; ignoring the death, ignoring the enslavement, and the terror that it actually stood for,” he said in a recent speech.

Good for news for New Orleans. But do such sinful remainders of slavery’s past go ignored across the celebrated precincts of Boston? And how should we deal with them?

Massachusetts was the first American colony to adopt slavery in 1641; its newly arrived white residents traded captured Pequot natives to Bermuda in exchange for the initial batch of African slaves who arrived on a ship named Desire. African slavery was born in the provinces of Boston and would last in the Bay State for next 140 years.

Over the 14 decades that slaves toiled in Massachusetts, odious anthems to human bondage in Boston were manifested.

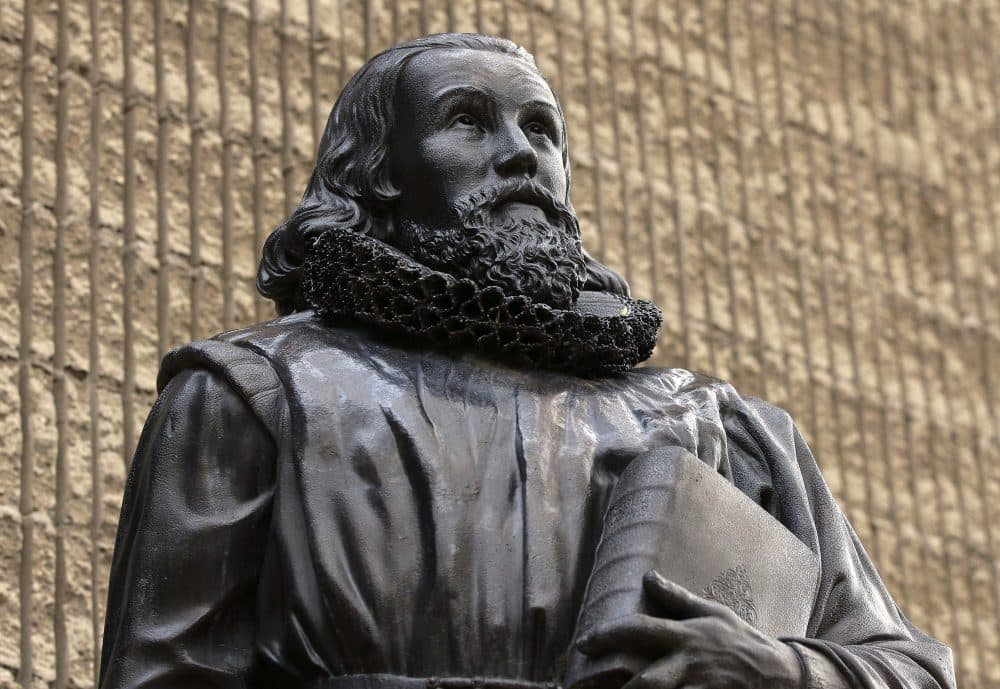

There is John Winthrop Square, named after the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, in downtown Boston’s financial district. While John Winthrop was also a founder of the First Church of Boston, he was among the first colonists to own slaves. The parcel of prime city real estate dedicated to Winthrop is in homage to his statesmanship, but should he also be publicly remembered as an owner of human flesh?

There is the Faneuil Hall Marketplace, which sits in the cradle of Boston’s government center. The structure was donated to the city by merchant Peter Faneuil whose enormous wealth was duly derived from slave labor. Faneuil owned five black people. The sale of “a strait negro lad” among many others slaves helped finance the building we now celebrate as a great civic space. Why is there no cry for reconsideration of that building's name or its removal? Perhaps a plaque can be erected at Faneuil Hall describing it properly as a “house built upon the blood of human chattel”?

Add to this list Boston's fifth mayor, Theodore Lyman. At the foot of Meeting House Hill in Dorchester sits a monument and park testifying to his greatness. Lyman is rightly recognized for improving the city’s public water system, but he was a staunch advocate of slavery. Lyman is said to have been a defender of women’s rights but he was no friend of universal freedom. Lyman presided over pro-slavery meetings.

After his death, a public school was named after Lyman in East Boston. It now houses condos and in 2014 was nominated to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Perhaps there is a lesson in civic courage that Bostonians can reap from the recent actions of the citizens in New Orleans? Maybe Bostonians can confront its current racial hauntings by looking deeply into its history and into the hearts and habits of the men it continues to glorify?

The past cannot be changed, but it can be publicly criticized. It cannot be altered through will or whim, but it can be put into a morally proper context that reflects our corporate contrition for past wrongs.

Indeed, apologies in Boston are now necessary to address the sins of our city’s fathers — to account for their historic wrongs and to acknowledge their participation in the blood encrusted practices of slavery. If we fail to admit to those sins of the city's founding patrimony, we may well continue the civic curse that perpetually plagues their progeny.