Advertisement

Commentary

LeBron Said 'Being Black In America Is Tough.' Bill Russell Would Agree

“History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes,” American literary great Mark Twain once said.

National Basketball Association superstar LeBron James may have been reminded of this on Wednesday morning when an unknown assailant painted an ugly racist message on the front gate of his Los Angeles home.

Although James was away in Oakland preparing for the opening game of his seventh straight NBA Finals appearance against the Western Conference champion Golden State Warriors, news of the disturbing incident quickly reached him.

He was noticeably upset. “As I sit here on the eve of one of the greatest sporting events that we have in sports, race and what’s going on [negatively in our society] comes again,” he told a somber press conference gathering that afternoon. While relieved his family was safe, James revealed this kind of harassment has traditionally been a common experience for African-Americans, who face the constant threat of racial violence and hatred on a daily basis.

“No matter how much money you have, no matter how famous you are, no matter how many people admire you, being black in America is tough,” he said. James also noted that racism takes on many forms, often concealed in our modern social media-driven society: “[P]eople will hide their faces and will say things about you and then when they see you they smile in your face.”

James’ thoughtful observations echo the sentiments of another basketball legend from the late 1950s and 1960s — a fateful time when “separate but equal” was still the law of the land in the Jim Crow South, and lynchings and beatings of blacks were commonplace.

A man without integrity, belief or self-respect is not a man. And a man who won’t express his convictions has no convictions.

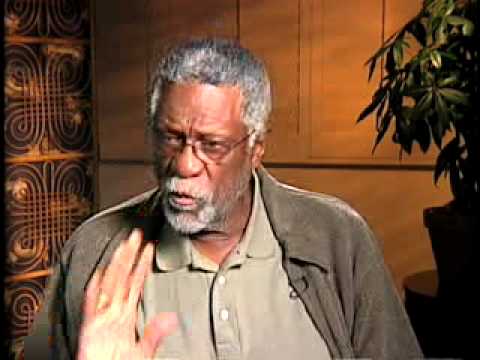

Bill Russell

Like James, Bill Russell was not shy about expressing his views, often in a provocative way. A native of Louisiana, the Hall of Fame Boston Celtics center and 11-time NBA champion did not so much address the issue of societal racial injustice as tackle it head-on.

Once, when the Celtics were scheduled to play in an exhibition game in Lexington, Kentucky, Russell became incensed when African-American teammates Tom Sanders and Sam Jones were denied service at a local hotel coffee shop. Without missing a beat, he packed his bags and flew out of town rather than subject himself to the racial hypocrisy of the situation. Blacks were good enough to play before a local white audience but evidently not good enough to have a late night donut.

As he told writer Ed Linn of Sport magazine in a 1963 article:

"For a great number of years, colored athletes and entertainers put up with those conditions because we figured they’d see we were nice people mostly and, in some cases, gentlemen, and they’d say, ‘Those people aren’t so bad.’ I’m not insulted by it, I’m just embarrassed. I’m of the opinion that some people can’t insult me. But it was the greatest mistake we ever made because as long as you go along with it, everybody assumes it’s the status quo. I couldn’t look my kids or myself in the face if I had played there. A man without integrity, belief or self-respect is not a man. And a man who won’t express his convictions has no convictions. I feel the best way to express my convictions is not to play. If I can’t eat, I can’t entertain."

Russell — the first black coach in major professional sports history — did not hold his fire when it came to the tense racial environment that existed in Boston during and immediately following his playing days. This was an era when de facto segregation in the public school system was an accepted reality and the vast majority of city blacks were shut out from well-paying white collar jobs. Even major mayoral candidates like former school committee chairperson Louis Day Hicks of South Boston could get away with campaigning on thinly veiled racial appeals to their white working class voting base. “Boston for Bostonians,” Hicks declared. No geniuses were required to determine this political call to arms was meant to exclude local communities of color.

Russell’s own suburban home north of Boston became the target of vandalism. Intruders broke into the property and left crude racist graffiti spray-painted on the walls. To add further insult to injury, someone had also decided to defecate in Russell’s bed.

“You know,” Russell commented to the Boston Globe, “I remember when [Carl] Yastrzemski was a rookie [for the Red Sox]. One of the writers said, ‘Too bad he ain’t one of us.’ This is what made Boston different for me. It really went past black or white. They would be into ‘Is he a Jew?’ ‘Is he Irish?’ ‘Is he Italian?’ And it seemed all the ethnic groups were contemptuous of each other. It wasn’t just that the whites were contemptuous of the blacks, or vice versa.

“You know, when I came to Boston, as a 22-year-old I didn’t know what a Jew was. But I became aware of it here, because people here make a distinction based on ethnic background, race, religion or whatever.”

As the decades advanced and Boston became a truly multicultural city worthy of its progressive revolutionary roots, Russell amended his views. But he no doubt would find agreement in what LeBron James said about his own recent brush with racial intolerance.

“We got a long way to go for us as a society and for us as African-Americans until we feel equal in America,” James posited.