Advertisement

Commentary

On Afghanistan, Trump Should Have Gone With His Gut

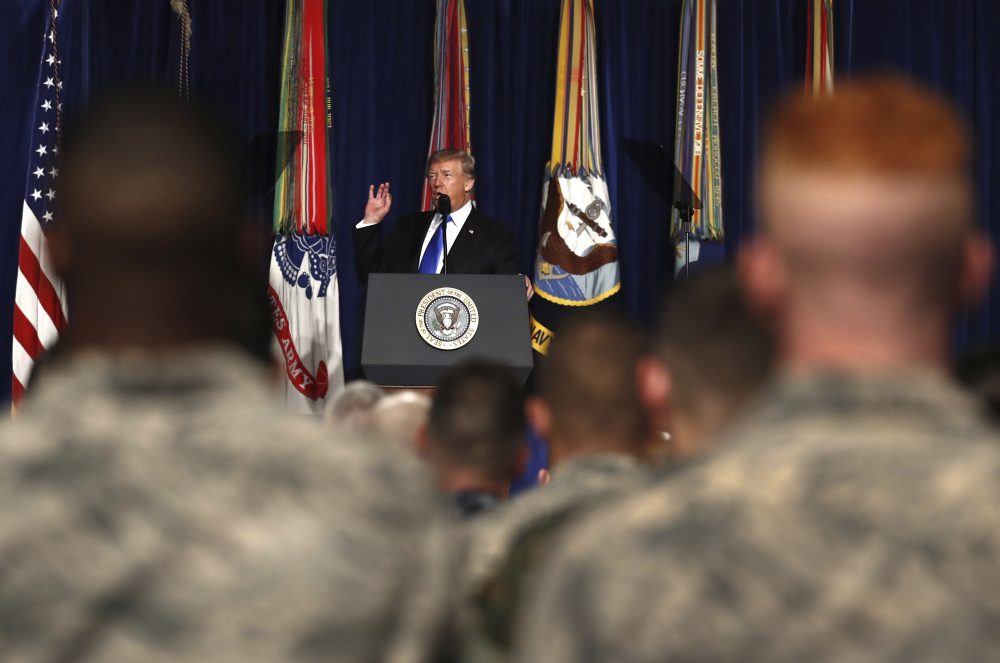

Unlike President Trump’s facile about-faces, his decision to escalate the Afghanistan war seems a case of surrendering a sincerely held conviction only after a fierce battle.

“My original instinct was to pull out, and historically, I like following my instincts,” he acknowledged last week in the speech announcing the military had convinced him “a hasty withdrawal would create a vacuum for terrorists.”

About 8,400 American troops are currently in Afghanistan, part of a 13,000-strong international force helping to train the country’s own military, which nevertheless has lost ground to the Taliban. Our soldiers also collaborate in counterterror operations with the Afghans. After campaigning last year on a drawdown, Trump reportedly agonized over his generals’ request for more troops and did everything but waterboard them to extract specifics of their plan before acquiescing.

Which is not to say his prolonged deliberations yielded the right call. I’m no expert on foreign policy, so when a matter as grave as war is on the table, I try to read expert opinion pro and con. That exercise leaves me in the unaccustomed position of wishing Trump had stuck to his gut and pulled the plug on what has metastasized into a disaster.

If we couldn’t win with 100,000 troops under President Obama, how will just one-fifth as many prevail?

First, while Trump refused to specify how many more trips he’d pour into Afghanistan — a secret it’s hard to imagine Congress and the public letting him keep -- his generals had requested up to 4,000 additional soldiers. Skeptics of escalation ask an obvious question: If we couldn’t win with 100,000 troops under President Obama, how will just one-fifth as many prevail?

The probable answer, says seasoned Washington Post foreign affairs columnist David Ignatius, is that prevailing, in this case, means not losing. Trump’s gambit “can sustain the current stalemate,” Ignatius wrote after surveying experts on the region. “This is a very limited version of success.”

Second, the Afghanistan war, 16 years old, is our longest war ever. Hoover Institution fellow Tim Kane, who supports Trump’s surge, praises him for “patience” that Obama allegedly lacked. The charge is comical. The American people have been more than patient with a fight that’s gone on longer than World War II, longer than the Revolution that created our nation, longer than the Civil War that almost killed it, and longer than Vietnam, a long slog to our defeat.

Advertisement

That last war shows that there’s a tragic difference between patience and pig-headed persistence in a lost cause. Banging our head against a wall makes no more sense politically and logistically than militarily. Retired Army colonel and Boston University emeritus professor Andrew Bacevich suggests that if we haven’t trained Afghans to competently defend and govern themselves after 16 years, there’s no reason to think “that more of the same — that is what Trump is proposing — will produce better results.”

Third, by one count, there are actually five conflicts shredding Afghanistan, including strife between ethnic groups. Our troops can’t solve that, as the Soviets learned when all their military might failed in this chaotic cauldron in the 1980s.

Fourth, while Trump's right that completely walking away could leave Afghanistan ripe for becoming a launch pad for terror attacks a la 9/11, there are other ways to address that danger.

Bacevich suggests a carrot-and-big stick approach. Assuming the Taliban continues to control large swaths of the country, we could offer them economic assistance as long as they play nice, and threaten shock and awe from the air if they don’t. (Afghan terrorists learned last spring that Trump likes to drop really big bombs.)

Additional options include keeping Special Operations forces and air power in the country to go after terrorist groups.

Fifth, Trump vowed we would not nation-build in Afghanistan. But one expert who supports the surge does so because he believes that’s precisely what Trump is doing. This analyst says efforts to build up honest, functioning institutions in the country have never been effective. He didn’t say exactly how that could be done, perhaps because nation-building is by nature a Wilsonian, utopian dream.

By contrast, Barry Posen, director of MIT’s Security Studies program, says pulling out would drop the Afghanistan mess in the laps of others in the neighborhood. That includes Iran, long a Taliban enemy, and Russia, which shares our problem with Islamic extremists and our interest in keeping the Taliban from harboring them.

Afghanistan, says Posen, “is a good place to create problems for America’s adversaries. And the best way to do that is to get out.”

One last point: Since 9/11, we’ve spent roughly $1 trillion on this war. (The toll in blood, of course, is worse.) Ask yourself as a taxpayer: Could you come up with better uses for that vast sum than 16 years of stalemate?