Advertisement

Commentary

'Blackbird' Endures As A Meditation On The Struggle For Civil And Human Rights

I was cleaning the kitchen, the radio paradoxically blaring an acoustic concert over the noise of a dust buster, when I heard the opening notes of "Blackbird," one of the most beautiful and enduring songs from The Beatles’ “White Album.”

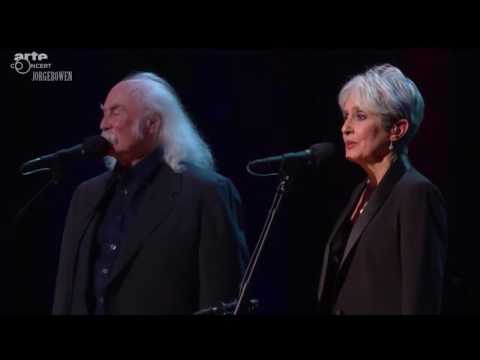

Joan Baez and David Crosby were performing the song at an event celebrating Baez’s 75th birthday. They sang slowly, deliberately. Crosby’s warm reediness braided with Baez’s crystalline alto to make the song sound newborn. This wasn’t an old favorite sung by old favorites; it was longing and lyricism taking flight, released by voices whose passions hadn’t aged. What I felt listening was not nostalgic, but awakened.

Blackbird singing in the dead of night / Take these broken wings and learn to fly / All your life / You were only waiting for this moment to arise.

Over the years, different stories have been told about the song’s origin and meaning. In some accounts, Paul McCartney wrote it in 1957. The blackbird was meant to represent a specific black girl (girls were “birds” in groovy 1960s England), one of the nine students courageously desegregating Little Rock Central High School. In other accounts, he wrote it a decade later, after reading about black liberation protests in the U.S.

Though the details vary, the premise remains the same. One man, moved by the aspirations of people a continent away, wrote a song.

In 1957, the struggle that so captured McCartney was the Civil Rights Movement. But by 1968, when the song was recorded, that struggle for justice and equality was referred to as the Black Liberation Movement, and the blackbird may have been a Black Panther. In 2017, when Baez and Crosby sang the song, the movement could have been #BlackLivesMatter, and the blackbirds Sandra Bland, or Eric Garner, or his daughter, Erica Garner.

For all of these people, McCartney’s refrain held true.

"Blackbird" was released in one of the most disruptive and defining years of the 20th century. The assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Bobby Kennedy, the police riots at the Democratic Convention in Chicago, the flares of freedom in Czechoslovakia that were doused by Soviet tanks — all of these upheavals and betrayals left young activists like me shaken and despairing.

Advertisement

By the mid-1970s, like too many privileged people for whom change was desirable — not essential — I surrendered to the notion that my ideals had been as acute and short-lived as a child’s first teeth.

I’ve never encountered leaders so bloated with hypocrisy and so contemptuous of the future.

But four decades later, in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis and recession, I looked around and saw a counter-culture manifesting itself in new ways. Zipcar and bike sharing, localism and community-supported agriculture; a do-it-yourself movement borne of economic necessity, but sustained by conviction. I saw righteous rage transformed into action, through the Occupy movement and Black Lives Matter. Our children were taking on the ills of the world in powerful ways, and I was both encouraged and revived.

Now, a year into the Trump presidency, I’m realizing that reaction is as tenacious as revolt.

In 1970, the first Earth Day celebration was held and “tree hugger” soon became a new epithet. Today fossil fuel profiteers have moved well beyond name-calling to actively sabotaging efforts to contain climate change.

In 1976, some Americans referred to Mexicans as “spics.” Forty years later Donald Trump sneered and blustered his way to the presidency by calling them “murderers and rapists.”

Some of the American Nazis who paraded in Skokie, Illinois in 1977 were undoubtedly alive to cheer 40 years later when another of their klan in Charlottesville, Virginia mowed down an unarmed protestor with his big fat car.

In 1991, President George Bush, nominated a man to the Supreme Court who had sexually harassed Anita Hill. Twenty-five years later a self-professed pussy grabber was voted into office.

It turns out the Reagan years — what I’d thought of as the last gasp of those who only feel tall by stamping down others -- were just a preview. Indeed, I can’t remember any point in my lifetime, or any point in American history, where the ruling elite has been so ready to sacrifice the planet and lives of younger generations to satisfy their own limitless greed. I’ve never encountered leaders so bloated with hypocrisy and so contemptuous of the future.

I am writing here about the past and the future because for too many years, I mistook periods of quiet for endings, dormancy for death. But "Blackbird" has endured for generations because its lyrics are always urgent, always true.

Blackbird singing in the dead of night / Take those sunken eyes and learn to see / All your life / You were only waiting for this moment to be free.

The past is present in the stories and songs our children hear from us. The future is being made daily, with and without our consent. History is born and lives in the now, in this moment, when we must once again fly “into the light of a dark black night.”