Advertisement

Commentary

Tom Wolfe And The Search For The Real

I once met a veteran newspaper editor who knew Tom Wolfe as a young reporter in the mid-1950s in Springfield, Massachusetts. Wolfe would become famous as an avatar of New Journalism, a term he himself coined in 1973, however, this old timer clearly had no use for anything other than the “just-the-facts” approach to news writing. He joked that if Wolfe wrote the story of President Kennedy’s assassination he’d spend the first five paragraphs describing how Kennedy looked and moved that morning, the parade route, the people lining the streets, and how he’d managed to get to Dealey Plaza in time to hear gunshots ring out.

Only then would he insert the most essential piece of information, that the president had been shot.

Tom Wolfe died Monday at the age of 88. It had been a long, long time since anyone asked him to simply stick to just the facts.

Indeed, Wolfe went from Springfield to the Washington Post in 1959, but wouldn’t spend much time writing so-called straight journalism. It was too confining; the 1960s were here, and change was happening all around. The years leading up to his 1962 arrival in New York and hiring by the New York Herald Tribune had seen the emergence of bebop, abstract expressionism, the Beat Generation, Off-Broadway, avant-garde film and photography, and, of course, rock ’n’ roll. Society was also changing, with the Civil Rights movement already gaining momentum, the first rumblings of feminism and the nascent drug culture. Wolfe figured, why should journalism remain unaffected?

That the post-war years were also a high point in American fiction was also a factor in the formation of New Journalism’s chief ethos. Wolfe, along with fellow travelers Norman Mailer, Joan Didion, Gay Talese, Truman Capote, Hunter S. Thompson and others, mingled fact-based journalism with literature and a you-are-there immediacy. They didn’t just organize facts, they told tales full of dialogue and structured like short stories. The glossy magazines of the day printed these pieces, and readers were quick to embrace this new form of reportage, which sought to raise nonfiction and journalism to heights previously achieved only in the pages of our greatest novels.

Wolfe’s stories and books formed an underground history of the times, a glimpse at America away from the stuff of headlines and nightly news updates.

Wolfe and the other practitioners of New Journalism sought a higher truth that went beyond the details of a given situation. Sociology, anthropology and psychology fed into the narrative, with the writer also bringing to bear his or her subjective eye. On top of a style that the New York Times referred to as “pyrotechnics,” Wolfe always had the facts, for he was a consummate researcher and reporter. Eventually, he would fill entire books with these stories, tales that were rich in language and detail that felt like they were being dispatched directly from the front lines of society’s most interesting places.

Wolfe’s stories and books formed an underground history of the times, a glimpse at America away from the stuff of headlines and nightly news updates. They chronicled -- to steal a phrase from Mailer -- the dream life of America. It was a time when readers were hungry for experience, and Wolfe was glad to put them on the bus with Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters (“The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test,” 1968), into space and back to earth again (“The Right Stuff,” 1979), and smack dab in the middle of America’s racial hostilities (“Radical Chic & Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers,” 1970). Along the way, he coined phrases such as “radical chic,” “the ‘Me’ Decade” and “pushing the envelope.”

Advertisement

Eventually, the demands of journalism were too confining for Wolfe, and he crossed over to write fiction. His 1987 debut novel, “The Bonfire of the Vanities,” was a huge success, combining Wolfe’s penchant for detail with a crackling yarn about a bond trader who finds himself caught up in a highly publicized case involving a hit-and-run accident. The themes of race, politics and class are in play throughout, and Wolfe demonstrated he knew well how to spin a sprawling tale.

Wolfe the novelist was taken to task by Mailer, who called his old friend “the hardest-working show-off the literary world has ever owned,” and accused him of selling out. Piling on in a very public way were novelists John Updike and John Irving. They viewed Wolfe’s intrusion into their domain as nothing more than journalism dressed up in fictional coattails. Wolfe struck back, poking fun in a piece called “My Three Stooges,” and all parties ended up looking less like esteemed men of American letters and merely petty scribblers feeling the march of time at their backs. The next three novels Wolfe would write were each worse than the previous — though 1998’s “A Man in Full” is not without its charms, 2012’s “Back to Blood” is nearly unreadable.

It is for his nonfiction that Wolfe will be remembered. Facts grow old and the world moves on, but we are by nature storytellers. Wolfe knew this and opened up his prose to let the world in, with all its messiness and chaos and incompleteness. He gave these various worlds he conjured structure and personality, and through them always found a way to get to the heart of the matter. His stories were alive on the page and because of this, they will retain a powerful resonance long after we’re all gone.

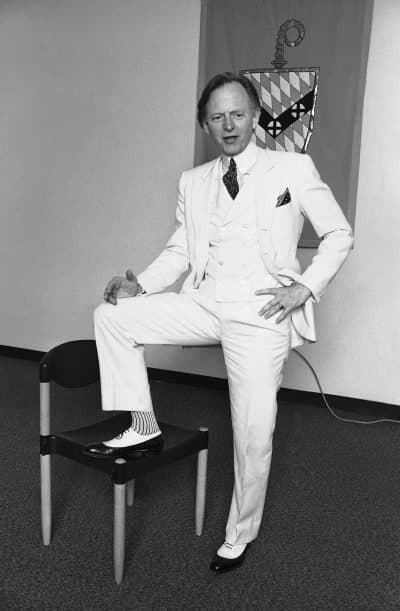

Of course, no tribute to Wolfe would be complete without a mention of his ever-present white suit, an outfit he first donned in 1962. When I met him at Brown University in April 1996, he was wearing the trademark getup, and delivered a talk that night that was optimistic about our nation on the one hand, but dour and dejected when it came to American society.

When asked what he’d like on his tombstone that day, Wolfe said, “He isn’t here.”

Lucky for American letters, he was here.