Advertisement

Commentary

The Brutal Reality Of Our Child Welfare System

It’s hard to imagine that President Donald Trump’s executive order to detain migrant families together while they wait for their day in immigration court will succeed.

First, the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California would have to modify the 1997 Flores Consent Decree that prohibits minors from being held for more than 20 days. Trump’s order did not limit the length of detention for migrant families.

The decree was intended to allow migrant children as much freedom as reasonably possible by prioritizing their release to family members or a facility with fewer restrictions than detention. But, as we have seen, the initial stage of such liberty has been the forced separation of more than 2,300 children from their parents or guardians in the past five weeks.

Many Americans have renounced the wrenching practice, declaring, “This is not who we are.” Unfortunately, it is very much who we are. The Trump administration’s treatment of migrant children at the border has exposed the brutal reality of the U.S. child welfare system. Children are taken away from their parents who are jailed, begin serving time in prison or are accused of abusing or neglecting their kids.

The foster care world is little publicized due to the privacy concerns of minors, but many have experienced it. There were 437,000 American children in foster care at the end of 2016.

It is deeply disturbing to hear an audio tape of sequestered children crying for their mothers and fathers and plaintively asking, "¿Que pasa?" or "What's happening?” American children who are taken from parents every day across this country have the same emotional and confused reactions. The public just doesn't see or hear it.

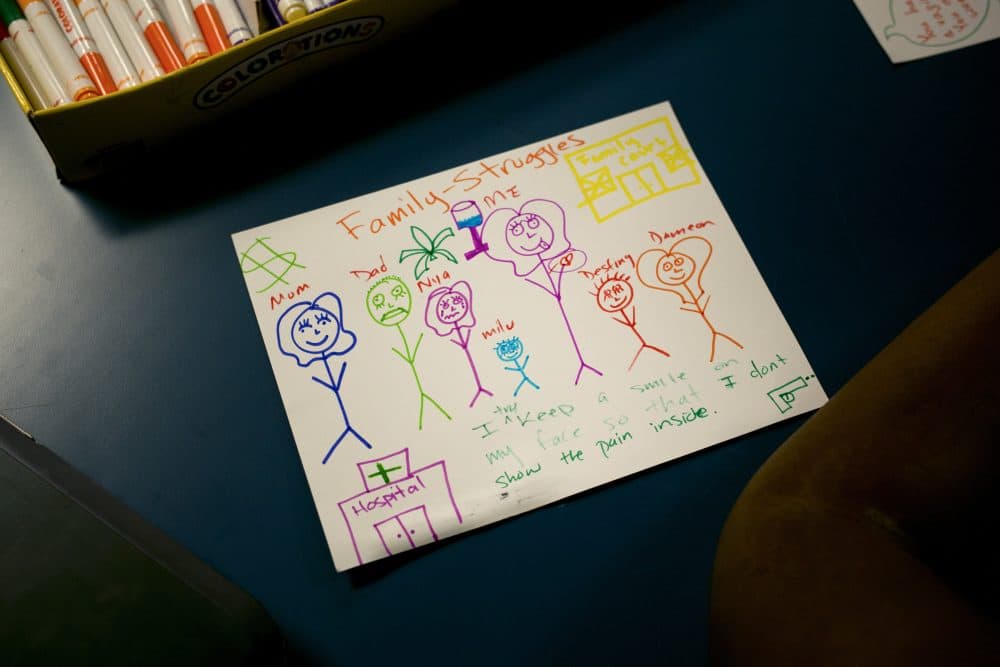

The first stage of protecting American children, dividing them from their parents, causes a whole new set of struggles for them by breaking maternal or paternal bonds. Afterward, children often don't know whom to trust. Some kids are too friendly to strangers, unable to tell friend from foe. Others become so defensive that they reject the very caregivers who could help them; the original loss was so great they cannot bear to lose anyone else. Many of these children remain angry at the system and their parents for decades. This is the paradox of foster care. In trying to prevent one harm, it causes another.

Trump’s zero-tolerance policy, charging migrant adults with a misdemeanor of illegal entry or a felony of illegal re-entry, has shined a light on the entire child welfare system. Just as incarcerated parents in the U.S. cannot take their children to prison with them, detained immigrant parents or guardians have not been allowed to live with their children. The children's fate lies with the Department of Human Service's Office of Refugee Resettlement. Last year, the office received nearly 41,000 children.

Advertisement

These migrant children are treated the same as American kids in foster care. If no other parent or guardian can care for the child, the agency searches for other relatives or a foster parent. The overwhelming majority of unaccompanied minors "are released to suitable sponsors who are family members within the United States (U.S.) to await immigration hearings," according to the Office of Refugee Resettlement.

While our hearts break for the migrant children torn from their parents, they may fare better than American kids. Nearly half of the migrants were over 14-years-old last year, while 59 percent of the Americans were younger than 11. Older children can usually cope better with temporary separations than younger children. Migrant kids spent an average of 57 days in the program while American kids spent an average of two years in foster care.

Trump’s new order calls for families to be housed together at facilities provided by U.S. government agencies. Although it sounds eerily like internment, it would be better than separating families and could initiate the kind of detention allowed in several countries for parents with children under 5.

In the best outcome, Trump’s order would initiate a change in the overall child welfare system: preserving bonds between mothers and fathers accused or convicted of nonviolent offenses and their children. However, the administration faces a steep challenge as it addresses immigrant children: Keeping detained families together without imprisoning kids.