Advertisement

Commentary

Lady Liberty's Call To Conscience

In 1958, my parents sent me to day camp at the Jewish Community Center in Newark, New Jersey. All I remember about those two weeks is swimming in a big blue pool and the elaborate camp-wide celebration for the fourth of July.

Risers were set up in the gym for the singing of patriotic songs. Campers made red, white and blue decorations for an indoor parade and pageant, and I got to be the Statue of Liberty, complete with paper crown, toga, book, torch and a speaking part: reciting the poem displayed on the statue’s pedestal. There was also a short introduction of the author, which began, “Emma Lazarus, an American Jewess …”

I had never heard the word “Jewess” and something about that hissing “ess” bothered me. In Lazarus’s lifetime (1849-1887), that label appeared in reviews her poems and essays — and she felt its genteel insult to both her gender and religion.

But in 1958 at the JCC, Emma Lazarus’s Jewess-ness was a point of pride. Several of my fellow-campers — like my brother and me — were the children of recent immigrants who were Holocaust survivors. We were already fond of the Statue of Liberty, but learning that the poem had been written by a “member of the tribe” made the big copper lady feel like she belonged to us as much as we belonged to her.

Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tossed to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!

Lazarus was inspired to write "The New Colossus" by the plight of Jewish refugees fleeing murderous religious persecution in Russia, but at the statue’s dedication in 1886, immigrants weren’t even mentioned.

Lady Liberty was celebrated as a symbol of the special relationship between America and France and their shared commitment to democracy and liberty. She was also heralded as a monument to the end of legalized slavery, only 21 years prior — a perspective that drew ire from the Cleveland Gazette, an African-American newspaper:

“Shove the … statue, torch and all, into the ocean until the ‘liberty’ of this country is such as to make it possible for an industrious and inoffensive colored man in the South to earn a respectable living for himself and family, without being ku-kluxed perhaps murdered, his daughter and wife outraged, and his property destroyed.”

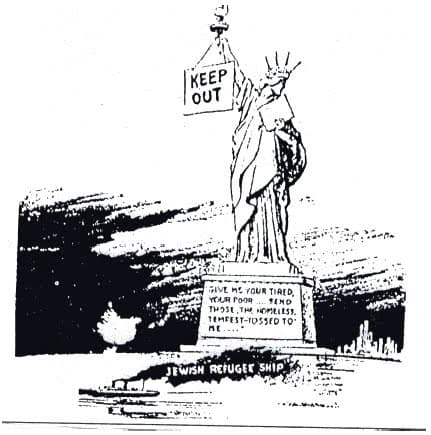

Lazarus’s poem became famous in the 1930s, when the United States refused entry to Jewish refugees fleeing the Nazi death machine. One political cartoonist scrawled her words of welcome across the pedestal and added a “Keep Out” sign to the Statue of Liberty’s upheld arm as a Jewish refugee boat sailed past her.

“Give me your tired your poor” has been a call to conscience and rallying cry ever since, and never more urgently than today, as The Lady with the Lamp has often been drawn with tears running down her cheeks and for good reason.

On this July fourth, the promise of America remains unfulfilled, incomplete and betrayed. But there’s hope in the first nine lines of the Lazarus poem, which offer a vision of an American exceptionalism that once inspired the world.

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

Advertisement

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor …

The colossal monument of the new world is not a sword-wielding warrior of antiquity, but a “mighty woman” with “mild eyes” who holds a book inscribed, July 4, 1776, the beginning of an unfinished experiment.

Emma Lazarus gave us a fierce “Mother of Exiles.” This is not a plea for mercy but a call to justice. She speaks in the imperative voice. “Keep,” she cries. “Give.” “Send.”

These are dark days in America, but Liberty’s lamp is still up in the sky and her demands resound down in the street, where her children are protesting the unconscionable imprisonment of the tired and poor.