Advertisement

Spirit In The Dark: Everyone Has An Aretha Story — This Is Mine

In 1967, I was a bookish, newly pubescent girl whose idea of heartbreak was informed by Smokey Robinson’s “Tracks of my Tears” and longing by The Beatles “Love Me Do.” Sorrow was expressed by a sweet falsetto, yearning by a quatrain of tight, simple rhymes.

Then I heard Aretha’s "I Never Loved a Man the Way I Love You."

The song starts with spare orchestration — an organ, a bass, a piano and a drum — then folds in new instruments, new layers of sound as it progresses. Aretha, playing piano, sings behind the beat right from the start when she declares “You’re a no good heartbreaker.” The volume mounts — two stanzas of slow-building rumination — until, in an explosion of grief from a woman betrayed, she nearly shouts, “How could you treat me so bad?”

The thing about that line — the quality that stunned me the first time I heard it and still electrifies me now — is that unlike any other singer armed with those lyrics, Aretha stressed the first part of the phrase — “How could you” — not the last. And that’s what made it real.

Aretha makes me feel something I can’t quite know, makes me know something I can only partly comprehend.

Think about when you’ve felt deeply hurt or enraged by someone you loved. What they did — steal from you, yell at you, cheat on you, disappoint you, take someone else’s side, leave you — that’s a blank to be filled in. But the essential emotional truth is always betrayal. How could you?!

In that song, I sensed something that, at the age of 13, I didn’t yet have the education or life experience to know. For the first of what would be many times, Aretha was out in front of me, jolting me, insisting that I recognize something I’d never really experienced.

Three years later, I got to see her live at the Crisler Center, the brand new home of the University of Michigan basketball team. It was a terrible venue for a concert — echoing, overheated and smelling of sweat — and my seat was in the second-to-last row, about two inches below the ceiling rafters. The show was short, almost perfunctory and strangely hollow.

When it was over, I made my way down to the stage — a platform in the middle of the basketball court — where I’d arranged to meet some friends. The house lights were dim, the road crew was packing up the equipment, and it was eerie and kind of cool to be one of maybe 20 people in a space that 15 minutes earlier had held 20,000. As I waited, a woman in sunglasses and a floor-length, white fur coat appeared, sat down at the piano, and began to play. She didn’t look at anyone or say a word. Aretha just played for a few minutes as if nobody was there, then got up and left.

I can’t remember the song, just the feel of those gospel-infused chords. But what I can’t forget was her ferocity and then her relief. She played like someone who had absent-mindedly driven off, then urgently returned home to do the one really important thing she had meant to do before leaving.

Advertisement

Release and resolve. Some say that "Respect" was the anthem of the black liberation movement, but listen to Aretha sing "A Change is Gonna Come" and you will want to weep and fight and embrace whoever is within reach, and then carry on. Sam Cooke wrote it, but Aretha made it a song not just about a person, but a people. I couldn’t have articulated this as a 13-year-old white girl, but I knew that this song was an illumination. Then and still, after hundreds of listens, Aretha makes me feel something I can’t quite know, makes me know something I can only partly comprehend.

Other writers in other tributes will talk far more knowledgeably about her amazing talent as a pianist, her versatility as a singer of jazz, pop, soul, and opera, and her ability to adapt to changing mores as the sisters started doing it for themselves.

They’ll point to her three-night gig at the Fillmore in 1971 — when she educated an adoring audience in how to achieve ecstasy without drugs — as one of the most astonishing, thrilling live albums ever made.

They’ll cite "I’ve Been in the Storm Too Long," her 1987 duet with Joe Ligon of The Mighty Clouds of Joy, as a lifetime of sorrow and yearning and joy compressed into eight glorious minutes.

They’ll remind us of how, at the Kennedy Center Awards honoring Carole King, Aretha made a president cry and a songwriter hear her own work as someone else’s gift.

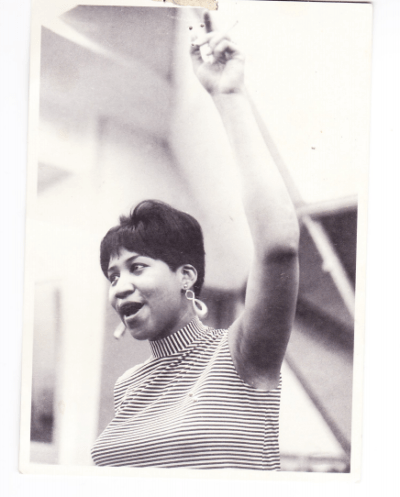

I can’t write those expert articles. My knowledge is too skimpy, and my appreciation too personal. But since I was in college over 40 years ago, I’ve had two items hanging over every desk I’ve ever sat at. One is “To Be of Use,” a poem by Marge Piercy. The other is a postcard, a black-and-white photo of a young Aretha — already the bruised and battered mother of two — in a striped, sleeveless turtleneck, taken at a recording session. Her mouth is open and almost smiling, her earrings are flying, and her left hand (with a cigarette tucked between two fingers) is raised. I like to think her arm is uplifted in joy, maybe even triumph.