Advertisement

Commentary

Art, Drugs And Money: How To View The Complicated Legacy Of Arthur M. Sackler

When my dad, the child of two immigrants, was a poor 8-year-old living in Brooklyn, he got a lucky break. One of his teachers arranged a transfer to a special elementary school, P.S. 181, where one of his schoolmates happened to be Arthur M. Sackler. I hadn’t thought much about my father’s friendship with Arthur until the current story raging over the Sackler family’s misleading claims about OxyContin and ties to the opioid crisis brought him back to mind.

My father (a novelist and short story writer) and Arthur were successful older men when they got back in touch in the 1970s. Together with their wives, they socialized, recalling their life-changing grade school and talking about their shared love for art — and “the arts.” To my parents, art gave life some of its richest and most redemptive moments.

To them, Arthur was a Brooklyn boy made good — a doctor, researcher, advertising executive and, ultimately, a very wealthy art collector. I imagine they saw him as someone who spent his money generously, to help people without great means gain access to beauty. Arthur’s passion for collecting, and his role in creating publicly accessible and gorgeous artifacts, made him interesting to them.

Arthur’s innovations in prescription promotion paved the way for Purdue Pharma’s even more egregious practices

Of course, now Arthur’s legacy is more complicated. While he apparently had no direct involvement with OxyContin or Purdue Pharma — run by Arthur’s younger brothers and their children — it seems Arthur taught his family much about how to push drug sales. He made his millions selling Valium, turning it into the first-ever $100 million drug. From Fortune Magazine:

Arthur’s philosophy was to sell drugs by lavishing doctors with fancy junkets, expensive dinners and lucrative speaking fees, an approach so effective that the entire industry adopted it.

Arthur’s innovations in prescription promotion paved the way for Purdue Pharma’s even more egregious practices, like rewarding doctors who over-prescribed OxyContin while hiding its extreme addictiveness (and blaming users when they became dependent). Just this week, Purdue Pharma agreed to pay nearly $275 million to settle a lawsuit brought by the state of Oklahoma. More than 1,600 other lawsuits against the company, including one brought by Massachusetts, are still pending.

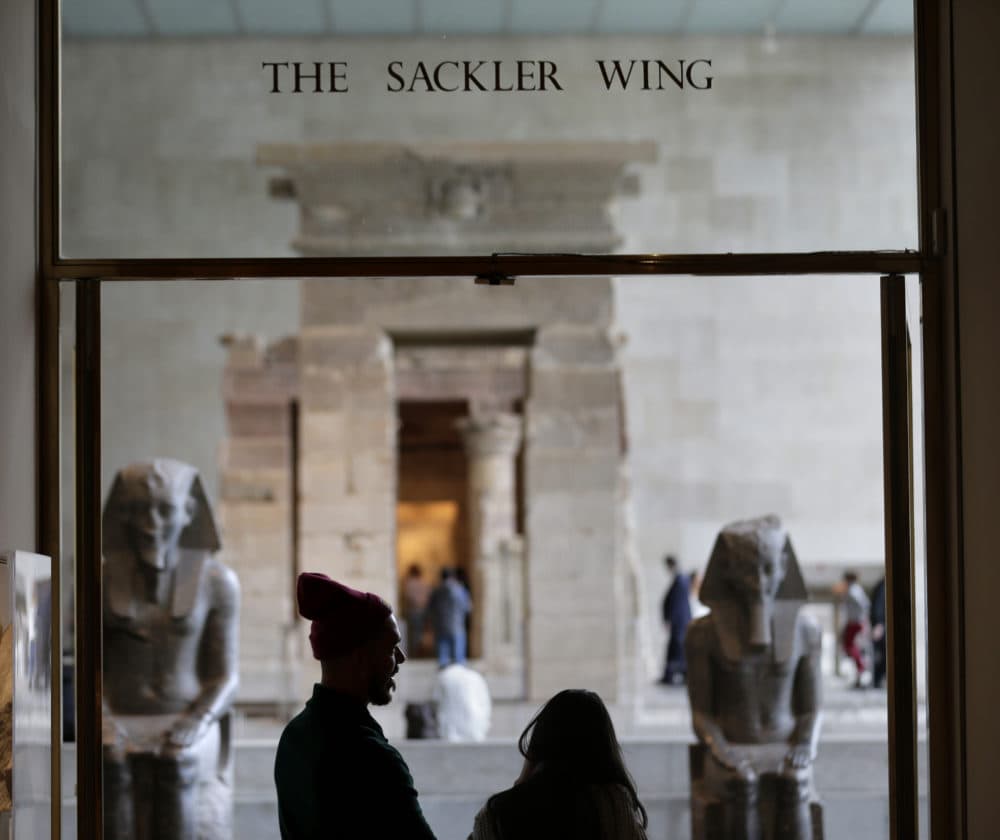

Arthur and members of his family have been generous donors to museums all over the world, including the Louvre in Paris, the Tate in London, the Guggenheim in New York City and a museum at Harvard University, among others. Many of these institutions are now wrestling with the question of what to do with donations that are the result of money made by the systematic and ruthless promotion of an addictive and dangerous drug.

This money/art conundrum isn't new. Ambiguously-gotten gains are used to purchase and donate paintings and sculptures, and the buyer’s money is bleached, starched and laundered in the transaction. A Bernini carving in a Renaissance church, a Matisse mural, a fresco by Piero della Francesca — all awe and delight viewers, while offering a fig leaf of public virtue to the patrons who have funded them.

Advertisement

Indeed, Arthur Sackler hardly stands alone as a rich person buying “indulgences.” And the institutions which solicit or accept donations of art, and gain wealth themselves in exchange for transforming embarrassment to pride — that stretch their own “good” names to cover any indecent elements of the trade — are a significant part of the ethical riddle.

In the 1980s when Harvard accepted donations from Arthur and named a museum for him, perhaps they — like my parents — didn’t know fully the unpleasant dimensions of the doctor’s aggressive practices, nor how it would flower in his descendants. (Though, Harvard’s vetters must have known that Sen. Estes Kefauver investigated Sackler’s practices in the early 1960s and was not happy with what he learned.)

How “dirty” money has to be before cultural institutions reject it is anybody’s guess. The Sackler Purdue Pharmacy lucre has lately turned too filthy to touch thanks to protest and bad publicity. Just recently, the National Portrait Gallery and Tate Museums in London, as well as the Guggenheim in New York City have stated they will refuse donations.

The reckoning we need is much larger than the Sacklers, even if it now rightly includes them.

I’m not certain where Arthur’s fortune falls on the continuum. I worry that the single gesture of chipping his name off a museum or two might obscure more substantial concerns. Harvard, and most institutions, wouldn’t exist without their appalling endowments of compromised money — whether from questionable drug marketing or other forms of exploitation and slavery. Such is the nature of capitalism and profit and corruption.

The reckoning we need is much larger than the Sacklers, even if it now rightly includes them. (The Sackler family's philanthropic trust announced this week that it would stop making new donations "until we can be confident that it would not be a distraction ... ")

Citizens and institutions alike would benefit from a larger process of truth-seeking. All the museums and non-profits that accepted gifts from any member of the Sackler family would do well to hold public conversations about their decisions, and about their endowments generally: how they justify gifts and naming; what lines they draw; what thoughts they have about altering practices and making amends.

Airing secrets is an important step in many kinds of recovery.