Advertisement

commentary

If We Commodify Space, Who's In Charge Of The Cosmos?

NASA recently announced that starting next year, the International Space Station (ISS) will be open to tourism and other commercial opportunities, such as advertising. Currently, the ISS houses a variety of research experiments by companies other than NASA, but the announcement heralds “a huge different way for us to do business,” according to NASA associate administrator William Gerstenmaier. The big question is whether this shift will slow the agency’s progress in meeting its already murky goals — or worse, whether it will change those goals entirely.

Space tourism is one aspect of the ISS’s new “Commercial Use Policy,” designed to “support the development of a sustainable low-Earth orbit economy," revenue generated by activity in near-Earth space. That makes sense in the long term — commercial and economic activity is vital to establishing a more regular and active human presence in space. If people end up living on the moon or on Mars, commerce will play a role in the success and eventual independence of those communities. At the same time, opening up the ISS to the highest bidders — a trip would cost tens of millions of dollars -- sets a dangerous precedent that could compromise NASA’s work, as well as its financial and public support.

Space tourism isn’t new. In 2001, American businessman Dennis Tito paid $20 million to accompany cosmonauts on an eight-day trip to the ISS. He brokered the trip not through the ISS directly, but through a company called Space Adventures, which offers three possible space experiences: a visit to the ISS, a spacewalk and a trip around the moon. The company has now sent space tourists to the ISS eight times. All of their clients are white; one is female. All are extraordinarily wealthy.

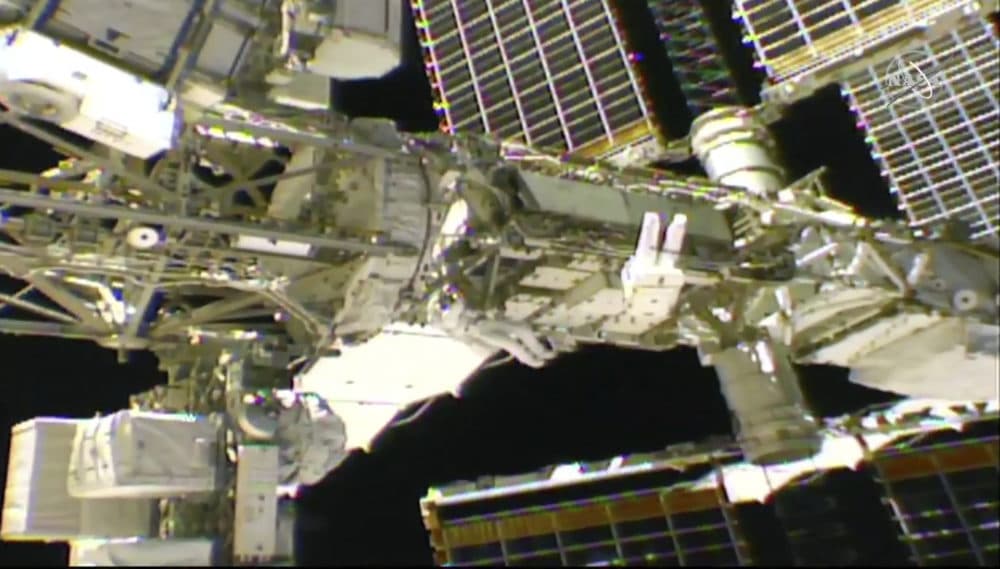

NASA astronaut Anne McClain and Canadian astronaut David Saint-Jacques float outside the International Space Station, April 8, 2019, as they tackle battery and cable work. (NASA via AP) The notion that space is only for the rich makes the cosmos, like so much else in this world, seem exclusive. Space itself does not belong to anyone (in fact, per a 1967 UN treaty, it cannot), but making the ISS a playground for the rich and companies leveraging zero-gravity marketing opportunities entrenches the narrative that space science is under the purview of the “liberal elite.” Not only is space science a luxury, but it’s one guided by those many resent.

A low-Earth orbit commercial economy makes sense in the long-run, but shorter-term needs necessitate it. The ISS and NASA are chronically underfunded, thanks largely to a false dilemma: Why spend money on space when there’s so much need on Earth? Opening the ISS up for business changes that question — why spend government money on space when private companies are willing to foot the bill?

Earning revenue from commercial interests and tourists frees up the ISS from reliance on decreasing budgets, which could enable projects that would otherwise be sidelined for lack of funding. But it also sets a dangerous precedent that the government doesn’t need to allocate money to the ISS because it’s making its own. If we can rely on private companies to generate income for the space station, then the government could use the station’s financial self-sufficiency as an excuse to decrease or eliminate funding. What implications would that have for governance of and investment in the station?

Advertisement

If NASA or the ISS relies on commercial income, who will call the shots when it comes to space exploration and research? The National Space Council announced that returning to the moon is a priority, which was also the goal of the Constellation Program under President George W. Bush, a project that was canceled six years later by President Obama. NASA embraced that directive and has vowed to return to the moon in 2024. But President Trump’s recent tweet undermines that goal (no, the moon is not part of Mars, but returning to the moon is part of the bigger plan to go to Mars) — especially because it came directly on the heels of NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine noting that Congress has to approve additional funding to make a 2024 moon landing a reality. The nation’s space program feels, as it often does, to be floundering for lack of specific and clear purpose.

The integration of commercial purposes may make the mandate of the space program muddier. It might be even harder to tell who’s steering the ship. What if the balance of interest and influence tips toward people and companies wealthy enough to conduct space business? The more we commodify space science, the likelier it is that capitalism will guide our pursuits. That’s a terrifying thought.

The prospect calls to mind Ray Bradbury’s "The Martian Chronicles," in which an entrepreneur sets up a hot dog stand on Mars. “We’ll be flooded!” he exclaims to his wife. “We’ll work long hours for days, what with tourists riding around seeing things, Elma. Think of the money!” While foolhardy, the venture proves irresistible. In the novel, humans destroy Mars and the Martians, and the only character who mourns that destruction puts his finger on why: “We Earth Men have a talent for ruining big, beautiful things.”

Hopefully, we won’t look back upon NASA’s decision to open the ISS for business with similar regrets.