Advertisement

My Father's Silence

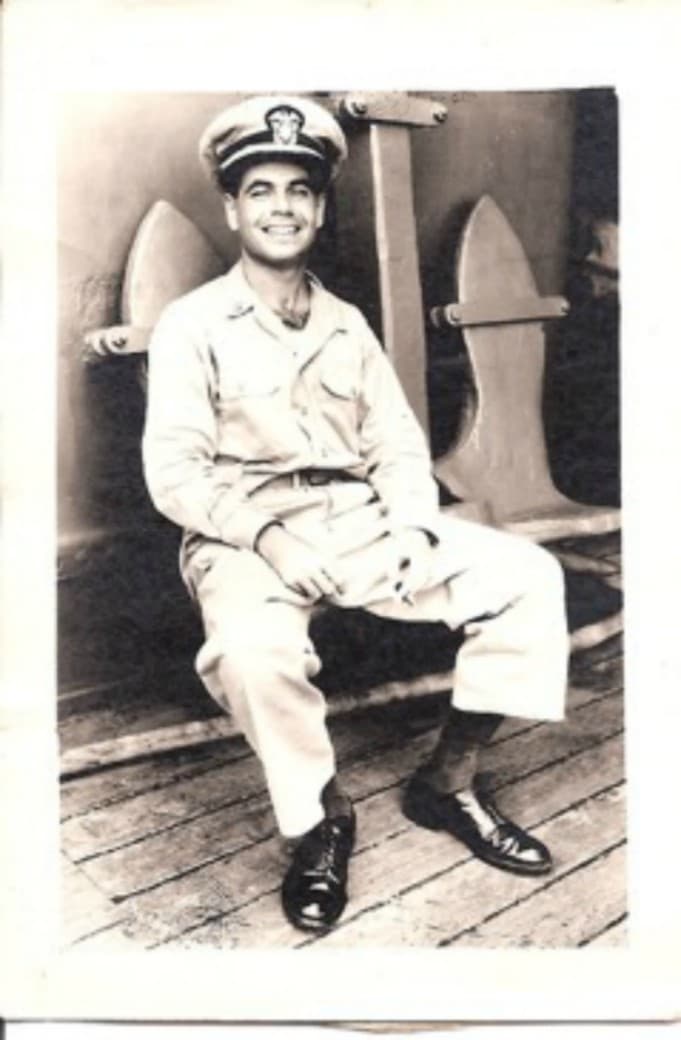

A few years after my father died in 2002, I sent away for his naval records. K. Harold Bolton, who served in the South Pacific during the Second World War, never talked about his time in the U.S. Navy. His silence about everything made me a snooping little girl, which turned me into a curious adult. There was nothing more I wanted to know than what my father had seen from the deck of his supply ship.

Apparently, I wasn't alone. A recent New York Times front-page article bore the headline: “Their Fathers Never Spoke of the War. Their Children Want to Know Why.” These children who span the generations want the same thing: to crack open their fathers’ silence about their war.

My father’s silence and his subsequent secrets have haunted me all of my life. My father, who was part of the "Greatest Generation,” is also a member of what the Times describes as the “Quietest."

His records arrived in a thick packet wrapped in brown butcher’s paper. As I avidly read them, the information that floated to the top was that he was exceptionally stubborn, inexperienced and always one of the youngest officers on any ship to which he was assigned. The numerous Reports on the Fitness of Officers in my father’s file consistently indicate that although he stood out for his bravery, loyalty and patriotism, in the end, he was an average, even naïve, officer.

This was not the answer I had expected when I examined the mystery of my father. Although I was thrilled to have the status reports, solid evidence that revealed facets of the man, they surprised — and ultimately, disappointed — me. I was so sure these reports would confirm that he was larger than life and, at last, make him understandable. Instead, the reports didn’t mesh with the man I thought he was. From the few pictures I had seen of him in uniform, I expected a capable officer who comported himself like a much older man.

Maybe this is the way most children see their parents — through a lens of time and story that ultimately fuses into lore. My father was the man who did push-ups every morning on the green shag rug of his bedroom. He was the man who walked a brisk two miles a day, even in winter. He expected his orders to be followed as he gave them. Yet blue-back nights when my coughing from asthma shook the house, my father stood guard by my bedroom window, gazing out, one of the few times I felt secure and loved.

Advertisement

I found a handwritten note in his file in which my perceptions of him as a young man became clearer. In the letter to his commanding officer, my father laid out his reasons for disobeying orders. He had been waiting to ship out in San Francisco the first Christmas after Pearl Harbor and wrote that he had decided to give the men under his command three additional hours of liberty to boost morale. At the very least, that unilateral decision must have incurred a reprimand.

I was so sure these reports would confirm that he was larger than life and, at last, make him understandable.

I also came upon a punishment meted out to my father. It happened toward the end of the war, when his commanding officer remanded him to quarters for 24 hours for going AWOL for a day. Disappearing like that didn’t seem in character. Yet the information rounded out the profile I was putting together of an officer who did not follow established ship routines and, according to notations from his commanding officer, did not “wish to acquaint himself with them.”

My father’s stubbornness also surprised me. He never properly learned to use the sextant for navigational calculations. According to his file, he was resistant to acquiring this new skill. But a spiritual part of me thinks that perhaps it was because those kinds of calculations demystified the heavens, while my father wanted to romanticize them. Over the years, I had seen glimpses of Dad, the romantic, who cried when he listened to opera on Saturday afternoons. Dad, the patriot, who cried when he listened to John Philip Sousa’s crisp, booming marches. Dad, the accountant, who finally, reluctantly, learned to follow established routines.

My brother, who became the keeper of the Navy stories Dad chose to share, had another version of Dad's punishment to supplement the Navy records. Our father was never AWOL, he says. The real story is that Lt. Bolton had fraternized with the ship’s black cook, called Cookie. Our father had stepped out of class and hierarchy, away from racism and inhumanity, to put his arm around a man who had just received news that his brother had died while fighting in Europe. He called Cookie by his given name, Ernie. The lieutenant also removed his hat in a show of mourning, making him technically out of uniform.

Finally, the lieutenant wept with Ernie on the deck of their ship.

Contrary to the jumbled, sometimes discouraging, naval reports, there was a promotion for my father by the end of the war. By the time the Navy honorably discharged Lt. Cmdr. Bolton in 1945, he had proven himself an exceptional man.