Advertisement

Commentary

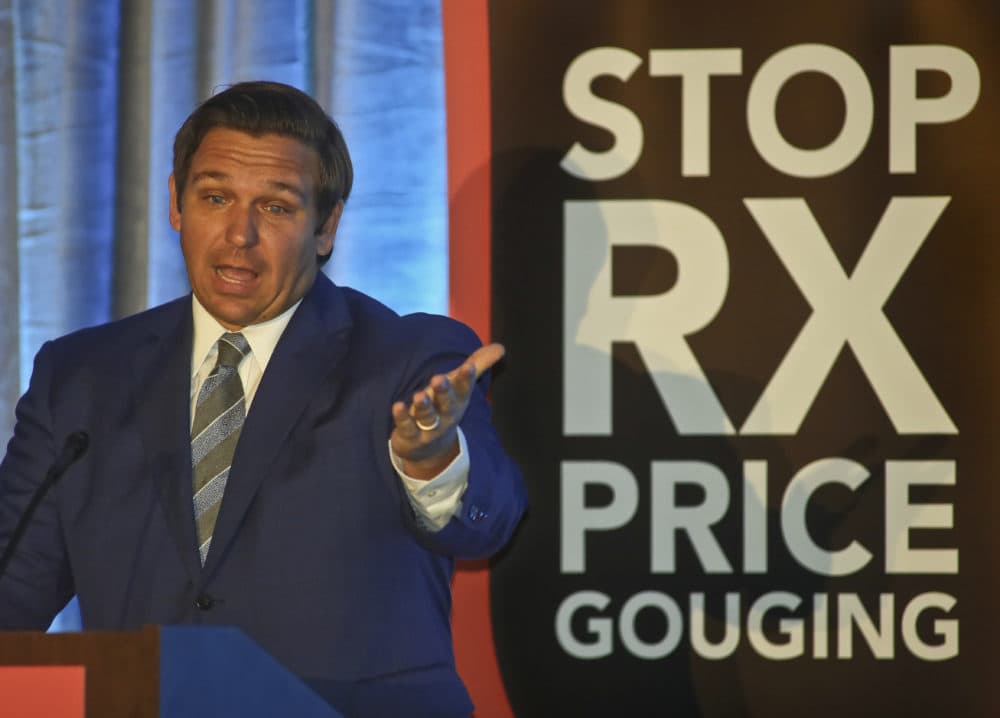

Ending The Cycle Of Drug Price Hikes, Death And Outrage

In 2017, the drug company Eli Lilly quietly tripled the price of Humalog, an insulin medication. The other main producers of insulin, Novo Nordisk and Sanofi, raised prices, too. Patients lost access to an essential drug, and many died of insulin rationing, leading to public outrage.

Politicians on both sides of the aisle united around the issue — an event about as prevalent as spotting a unicorn in Central Park.

The story looked bad for Lilly. Then, in May, the company released Lispro, a less expensive authorized generic version of Humalog. Lilly also established a “Diabetes Solution Center” for patients who use Lilly insulin but are unable to access it. Great, right?

Nope. Eli Lilly, criticized for jacking up the price of Humalog, didn’t lower the cost. Instead, they released a cheaper version of the same drug, built what must be an incredibly expensive “solution center” for a problem that they created, and praised their own generosity for doing so.

[Eli Lilly] ... built a ... “solution center” for a problem that they created, and praised their own generosity for doing so.

Those “solutions” are not enough. It costs Lilly between $78 and $133 to manufacture a year’s worth of Humalog for a single patient — and they’ve priced Lispro, the generic, at almost $140 for just one vial.

Prescription drug costs are higher than they should be, at about 15% of total health care spending nationwide. And they’re increasing, at a rate out of proportion with the growth of the overall health system. The Massachusetts Health Policy Commission, a government agency that monitors and controls health care system costs in the state, showed that prescription drug costs in Massachusetts grew by 4.1% per capita in 2017, while total health care expenditures in the state grew by only 1.6%.

I’ve cited state and federal numbers for prescription drug costs overall, instead of only the numbers for insulin, because we don’t just have an insulin problem or an Eli Lilly problem. We have a systemic problem — one of under-regulation and the misplaced incentives of pharmaceutical companies.

People dying for lack of access to drugs will happen again, of course. Epi pens, HIV drugs, the list goes on. We will be shocked and outraged. More deaths, more tweets, more congressional hearings. A brief respite — then, more price hikes.

Lilly hiking up the price of Humalog is like an infection contracted by an HIV-positive patient. The infection is problematic in itself, but it is not the systemic problem. Treat the infection, and another will follow. You have to treat the underlying virus to end the cycle.

What would an effective solution look like? We need comprehensive federal legislation with teeth that prevents unreasonable price hikes for prescription drugs. The U.S. doesn’t often restrict for-profit companies, but we do put certain limits on predatory practices, through antitrust laws, for example. Pharmaceutical companies are crossing clear boundaries with these price hikes, and we need to establish, and enforce, laws for acceptable behavior.

State laws can serve as interim solutions and as models for future federal legislation. Colorado recently passed a price cap law for prescription insulin, for example. And while helpful for patients affected by insulin prices, it won’t prevent this from happening again with other prescription medications. A bill proposed in Massachusetts could model a more comprehensive approach. It would authorize the Health Policy Commission to set price limits on drugs following unreasonable price hikes.

Lilly hiking up the price of Humalog is like an infection contracted by an HIV-positive patient.

At the federal level, the future of prescription drug policy is uncertain at best — the past few years have seen a high ratio of talk to action. President Trump’s administration released a proposal in 2018 that would allow Americans to access cheaper, foreign-made generics, but the administration didn’t follow through. Trump recently claimed that drug prices have declined, but hasn’t offered any evidence of that really happening.

Sweeping legislative reforms require significant justification. Defenders of the status quo argue drug companies are for-profit entities — in America’s capitalist system they exist to make money, not to help people. Developing lifesaving drugs costs money, and they need to make money to do so. But these drugs aren’t new, and companies are far from strapped for cash.

Candidates running for the 2020 Democratic nomination have been talking prescription drug prices. Bernie Sanders, like Trump’s administration, has proposed that Americans be able to access cheaper generic drugs from international markets in certain circumstances, and he has promoted numerous other policy mechanisms to decrease prescription drug costs, including at a system-wide level.

Kamala Harris is pushing to curtail drug price hikes through legislation, too. Elizabeth Warren has, arguably, the most audacious proposal on this: allow the federal government to produce authorized generics when prices get too high. But the current leader of the pack, Joe Biden, hasn’t said much on prescription drug pricing, and he has a problematic record on the issue from his days in the Obama White House. It’s hard to know who will reach the Oval Office, or what they’ll try to do — let alone, successfully do — when they get there.

But this much is clear: Drug companies are making money off of people with chronic diseases — and off of all of us — because higher drug costs passed on to insurers translate to higher premiums for everyone.