Advertisement

Commentary

In The Japanese Snow Queen, I See My Mother, My Daughters And The Future

It is this scene in countless Nutcracker productions that makes first-timers gasp. Several notes before the faux snowflakes begin their languid descent onto the stage of the Cutler Majestic Theatre, my eyes instinctively snap skyward. My body knows what’s coming. The staccato notes of Tchaikovsky’s “Waltz of the Snowflakes” quicken, ethereal voices come in over the orchestral music as the dancers float in unison, white tulle billowing, toes on pointe.

The music sparks a memory: I am 6 years old again, with Gamma at George Balanchine’s The Nutcracker, performed by the New York City Ballet. I am watching a predominantly white cast, sitting next to my white grandmother.

I think nothing of it.

As an educator in the field of diversity, equity and inclusion, I often hear and share about the importance of students “seeing themselves” in their teachers. As a biracial woman, I have struggled to apply this concept to my own life. Watching José Mateo Ballet Theatre’s Nutcracker this year with my Japanese mother, I experienced theory come to life: I saw Mama in the Japanese Snow Queen, and myself in the multiracial Sugar Plum Fairy.

At the end of act two, the Sugar Plum Fairy and her Cavalier, danced by a Black man, have the stage to themselves for 10 glorious minutes. It does not matter that the set is minimal, or that the little girl seated across the aisle, who has been chattering away throughout the show, continues her soliloquy. I hear nothing but the recorded music. I see nothing but taut calves and graceful arms, precise twirls and powerful leaps that elicit eruptions of applause, as the two command the stage, both as a pair and during their solos. I see the future of ballet. I see this penultimate series of dances — choreography that I’ve almost memorized — anew.

My mother carries scars from when she was forced to give up her dream. The Bolshoi Ballet, with whom she was a dancer in Tokyo in the 1970s, invited her to move to Russia, but my grandmother said “No.”

"Her actual words were, 'you'll have to murder me first,'" my mother has told me. "Anri, it was the mid '60s, to your grandmother, Russia was like the other side of the world. She was worried that if I went, I would never come back."

Gamma, my father's mother, has been dead for three decades now. My relationship to the Nutcracker is one more way in which I can trace my matrilineal connections: from grandmothers to mothers to daughters and back. Ballet is in my DNA. But I quit at 7, the age of my middle daughter who is a mouse in the José Mateo production. She adores being onstage in her grey fleece suit, and later eating candy backstage with her rodent cohort. Her mischief. Her older sister is also in the show, having graduated from mouse to polichinelle.

Representation matters. Mr. Mateo’s production, which is open through Dec. 22 for it second run this season at the Strand Theatre, allows for so many more of us to see ourselves. For a fleeting moment, I was watching my mother soar above the Snow King as he hoisted her aloft. I pictured my girls, backstage in their costumes, seeing more of themselves as the dancers leapt offstage, clearing the way for their eager, young castmates. Seeing too, that once they come off stage they become real people again. No longer the Snowflakes who seem to not even breathe, they undo their costumes, freeing their sweaty, sinewy backs to rapidly expand and contract as they gulp the backstage air.

Advertisement

As I sat next to my mother at this year’s show, the third season that my daughters have been in the cast, I could feel her watching the life she could have had leap before her onstage: lithe, muscular women, clad in tight-fitting corset tops with layers of perky tulle, landing noiselessly on the tips of their well broken-in toe shoes.

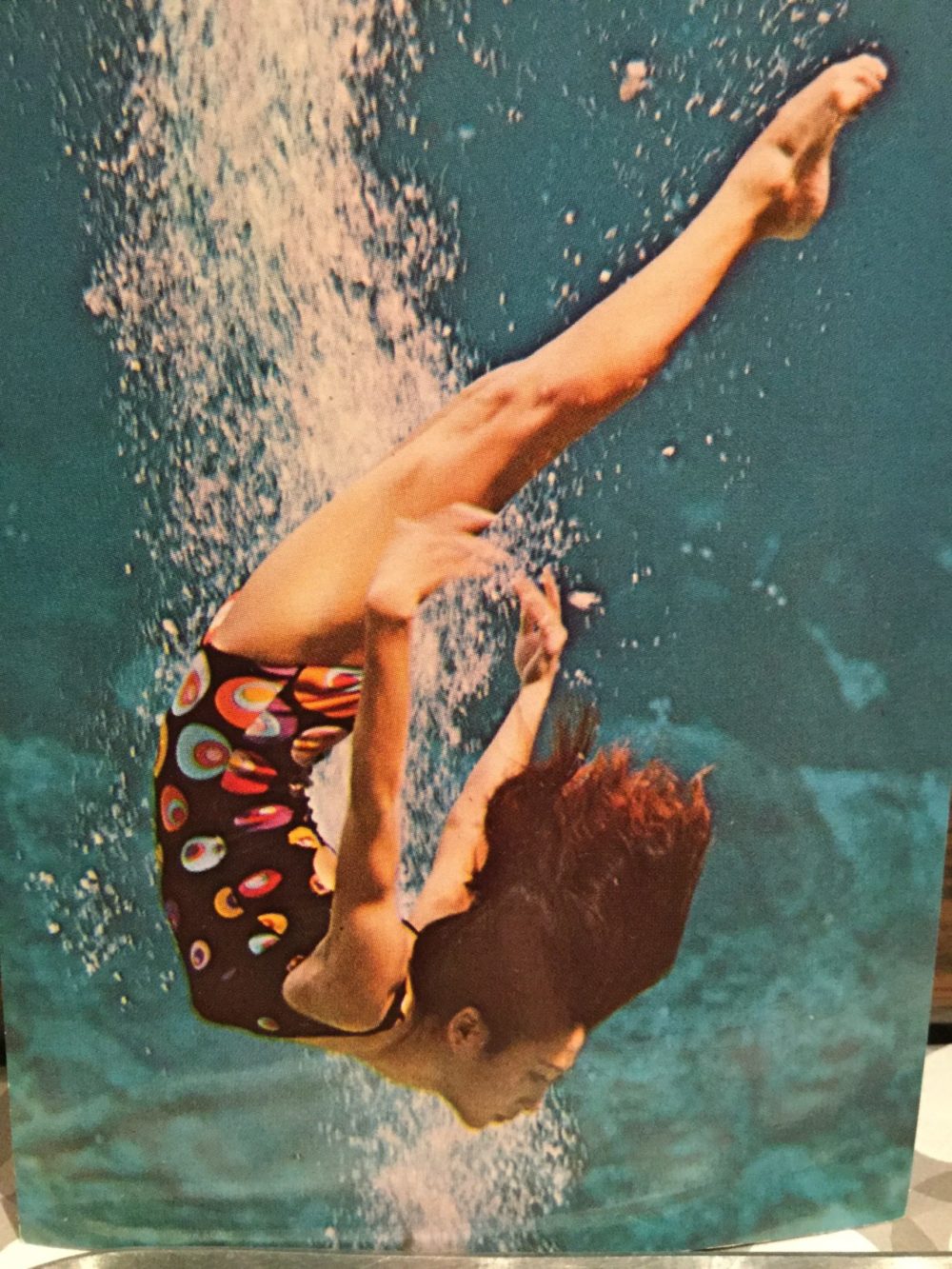

We don't talk much about her ballerina days. When I was younger and would ask about them, she'd say that had she gone to Russia, I would never have been born, so it was worth the trade. When she left the Bolshoi, Mama began performing underwater ballet at Yomiuriland in Tokyo, then moved to the U.S. where she became the first mermaid of color at Weeki Wachee in Clearwater, FL.

I do not have illusions of professional ballet careers for my girls. I hope that their time skipping and scurrying across the stages of the Cutler Majestic and the Strand will help preserve some of the confidence that can become scarce post-puberty. For as long as they ask to audition for the show, I won’t think about rehearsals and performances taking over our fall weekends. I will think about my mother, and say “Yes.”

José Mateo Ballet Theatre’s "The Nutcracker" runs at the Strand Theatre in Dorchester through Sunday, Dec. 22. More info here.