Advertisement

Commentary

In Times Of War (And Coronavirus) We've Always Relied On Women To Sew

"Send socks!" begged soldiers on both sides of the American Civil War.

More than 155 year later, American health care professionals today plea, “Sew masks!”

Our nation’s wartime history can be understood, in part, by the millions upon millions of women’s volunteer hours in the production of handcraft — with generally no compensation for supply costs — as a hard-scrabble attempt to offset their fellow citizens’ woefully inadequate, and mortally dangerous, situation on the front lines.

For first responders, medical professionals and eldercare workers today, this should sound alarmingly familiar.

While handmade cloth masks aren’t as effective a barrier to prevent the spread of illness as their mass-produced counterparts, right now they may be the quickest way to combat a shortage of medical-grade masks. With the CDC now calling on medical professionals, without access to life-saving PPE, to wrap a bandana around their nose and mouth as a last resort, hospitals have acted on their own accord, asking home sewists to produce face masks en masse, which — thanks to elastic or ties — can offer a more secure fit than a tied bandana.

With presumably thousands of (mostly) women sewists throughout the U.S. sitting down to their sewing machines, it would behoove us to situate their handwork on a long thread of women crafting for the national cause during war time.

During the Civil War, soldiers in battle wrote home begging for cold-weather clothing, and women answered the call “though neither the Union nor Confederate government had asked (women) for help,” according to historian Anne L. McDonald in her book, “No Idle Hands: The Social History of American Knitting.” Handknit goods were considered far superior in terms of quality and warmth than warm-wear provided by Uncle Sam, when such provisions were even available.

The preponderance of women knitting became such a social force during the Civil War, that the composer Albert M. Hubbard penned “The Knitting Song: Dedicated to the Patriotic Ladies of the North.” The lyrics proclaimed:

Knit! Knit! Knit!

For our Northern soldiers brave!

Knit! Knit! Knit! While the Stars and Stripes they wave!

In the North alone, so many aid societies were formed for the care of soldiers, buttressed by the knitwear production of women on the home front, that it precipitated the founding of the United States Sanitary Commission, considered the precursor to the Red Cross. In Boston alone, records from the Sanitary Commission indicated donations of 34,138 pairs of socks.

During World War I, women were on the hook again to outfit warm-wear “for the boys” through their production of knit items. “Knit for Sammie!,” the American Red Cross urged (drawing upon the nickname for Uncle Sam), when a Red Cross member catalogued the agency’s stockpile of warm-wear and castigated it as barely sufficient to protect American troops during winter combat. The task for American women was formidable, according to an essay by Paula Becker:

"[The Red Cross’s] immediate need was for one and a half million each of knitted wristlets, mufflers, sweaters and pairs of socks. The need for the socks was paramount: The trench warfare conditions under which the war was fought meant that soldiers spent weeks or months entrenched in wet and in winter freezing conditions."

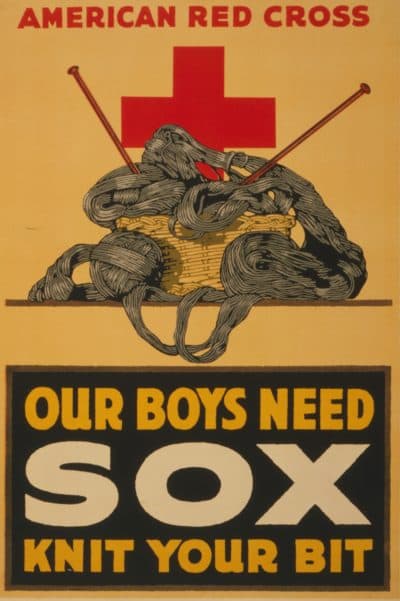

Indeed, the rather racy World War I slogan from the American Red Cross, “Our Boys Need Sox: Knit Your Bit,” became the rallying cry of legions of American women across the land; the Daughters of the Confederacy knit 600,000 items of warm-wear for American soldiers.

Today, America’s sewists are not crafting “for the boys” — especially since women are on the frontlines fighting COVID-19, according to the World Economic Forum — but for a healthcare system teetering on a precipice.

When there’s a failure in the capitalist system (when supply can’t meet demand) or a failure on the political front (when President Trump stalled in enacting the Defense Production Act), we see a surge in American production that’s socialist and gendered: American women are today devoting themselves to answering the pleas of medical professionals, to improve public health.

The phrase “American made” rings of homeland manufacturing. But in this case it’s homeland handcrafting, put in stark relief from the cheap, disposable — and now unobtainable — masks that are so often mass-produced in China, exploiting cheap labor.

Perhaps our current situation is a reason why schools should reclaim another part of American history: Home economics. Its decline in recent years can be understood as test scores and career preparedness became the academic focus, as women’s role in the workforce became ascendant and as many women eschewed “domestic” traditions and responsibilities. But this time let’s decolonize the gendered aspect of the domestic sciences.

After all, crafting is as calming as a Xanax without the deleterious effects, and sustainably focused resell shops of donated craft goods allow folks to acquire used materials often times for pennies.

The home sewists’ work may be necessary but it’s certainly not novel, at least not in the history of this nation. It’s American women makers who have been crafting the gaps to aid those on the front lines for centuries — whether the enemy is human or pathogen.