Advertisement

Commentary

Helping East Boston’s Most Vulnerable Residents, Block By Block

Three weeks ago, I made my first delivery. Esperanza opened the door, her eyes lit with surprise. “Dios la bendiga,” she told me a few times through her mask. "God bless you." I also felt happy surprise when my phone pinged later that day with an $18 Venmo payment. Another family who had offered to pay for the bag of milk, eggs, cheese and bread came through. Their commitment meant we really could care for each other.

When the federal stimulus bill was approved March 27, recognition seeped through our neighborhood, East Boston. Undocumented workers, who keep our take-out hot and our healthcare facilities clean, would be left out. Our neighborhood’s collective knowledge could have forecast this.

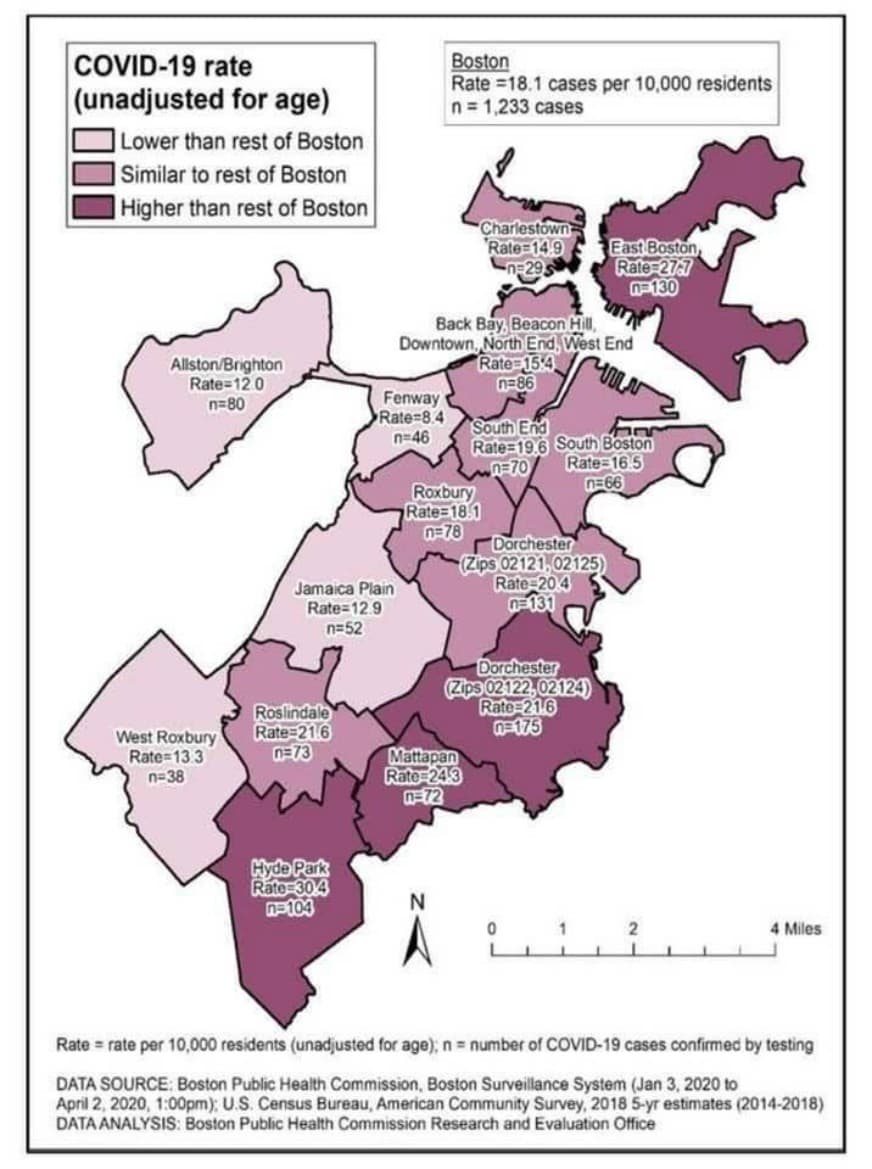

A week later, East Boston measured the second-highest number of reported cases per 10,000 people: 50 percent higher than the citywide average, according to the Boston Public Health Commission. More of our residents continue to take public transportation to work.

I’m an after-school teacher, experimenting in remote teaching, while some of my students' parents still commute to their job sites. Charlie Card taps were down 83% across all lines, but only 69% on the Blue Line — the train that carries our working-class neighborhood to downtown opportunity.

For some Eastie neighbors, staying home means missing pay, without the promise of an unemployment check. Leila, my first-generation student, has been moving between three houses each day, following the ebb and flow of her parents’ work schedules. Sometimes we catch her in the car for our Zoom calls, writing notes in the condensation on the windshield. She comes to every call but says it's hard to do her school assignments because she’s always on the go.

My six students and I are working on public service announcements — messages we think the world should hear at a moment like this, recorded on our phones from our bedrooms. They tell stories of how we should stay inside, what services are being offered to homeless residents and why young people are feeling mad about school closures. (One young person even showed us how to wiggle a cookie from our forehead into our mouths with no hands.)

Ask any one of us if students would have been mad about a spontaneous extended spring break a month ago, and none of us would have guessed yes. We miss the social contact, and each Zoom call offers a space to recreate it, to find new ways of being a team.

Block by block, we're connecting with our neighbors.

By the time Congress voted on the stimulus package, a mutual support network had already germinated in Eastie, each day wrapping new neighbors into its folds. From the outside, it’s subtle. From the inside, it's loud — powerful enough to bust through paradigms of entitlement, work, survival and love.

Neighbors share hundreds of messages in this network each day. They come via WhatsApp: requests for food, templates of letters to share with landlords on the first day of the month, applications for workers’ emergency funds.

Neighbors United for a Better East Boston calls everyone on the voter registration lists. ZUMIX teaching artists contact parents to offer remote music lessons and delivery of diapers. The Ayni Institute -- "ayni" means "reciprocity" in Quechua -- trains local leaders to build organization and strategy. The Center for Cooperative Development and Solidarity connects with their circles of workers, who've been learning about cooperatives as a path toward economic justice. Upwards of 250 families have offered or received support since the onset of social distancing, our records show. And these are only the interactions we've written down.

This island that we’re planted on has prepared us for this.

About a year ago, a group of Eastie organizations formed PUEBLO Coalición with a shared concern about housing displacement. Speculation and development were driving up rents and uprooting people from their familiar contexts. We’ve spent this year building relationships, learning new structures for work, practicing accountability to those that live next door.

A virus and new development are not so different. They can both aggravate deep social inequities. When we look at the patterns of our neighborhood, we see stacked challenges: housing insecurity, pressure to work, sickness. And with each layer, our network of neighbors is learning to adapt.

A community response of hundreds of messages and calls reminds us that finding solutions is a practice. Walking down any street in Eastie these days, you'll see shuttered corner stores and a hopeful chalk message here and there on the sidewalk. The potential energy of this network simmers within the minds of residents, behind doors, across digital space and occasionally, in a bag at someone's doorstep.

We’ll continue to teach. We’ll make many more deliveries, and each time, we'll be less surprised by the reliability of our connection. We’ll remember that so much of what we need and what we have to offer is right here.