Advertisement

Commentary

'Two Weeks Ago, He Moved Out': What It's Like To Have A Family Member On The Frontlines Of The Pandemic

I’m on week five of social distancing as a frontline family, and I’m hitting a wall.

My husband is an ER doctor south of Boston. As director of the department, he’s worked 14-hour days since the beginning of March. First we relied on a multi-step decontamination process in the garage to prevent COVID-19 from coming home with him. Two weeks ago, he moved out of our house, onto a boat we bought last winter — we’ve never sailed it, but it has cabin. It’s docked about 45 minutes away, close to the hospital.

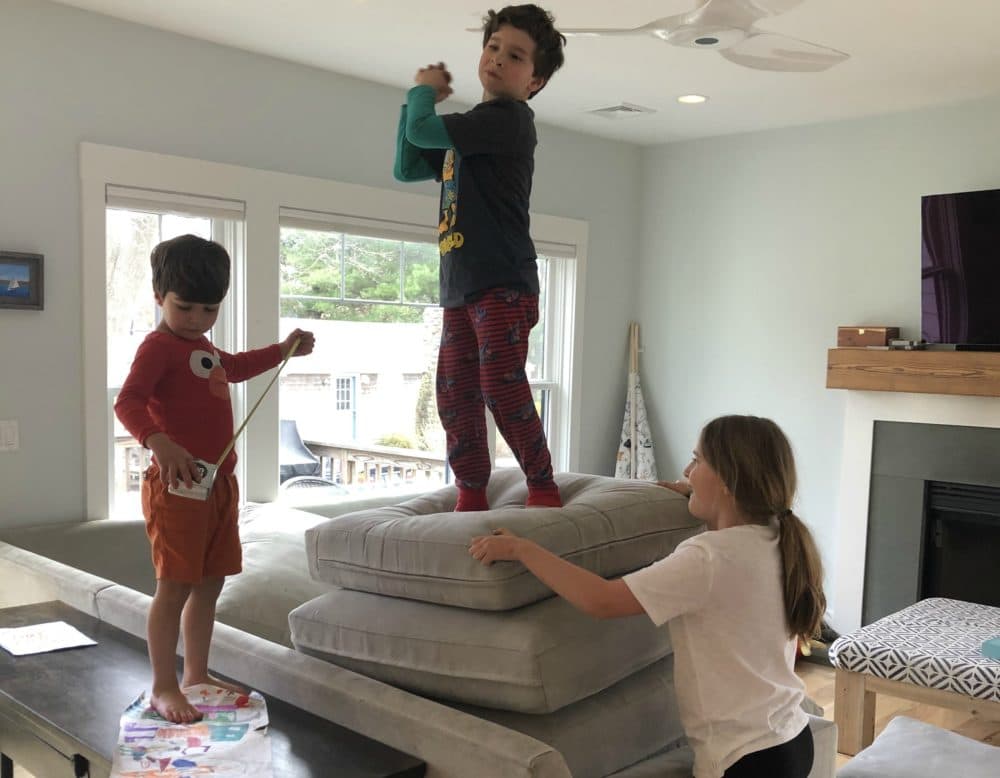

Housebound with three young kids and a spouse on the front lines of a global pandemic, I have some coping strategy FOMO — no nature walks or sourdough starters here. My 10-year-old says she feels like an inmate. My 7-year-old wants to drop out of distance learning. My 3-year-old is a 3-year-old.

I’m alone with my kids, more worried about personal protective equipment (PPE) than homeschooling, but struggling like everyone else to find some temporary normal.

Yesterday I tried to coax my son, the 7-year-old, through a math assignment, a word problem about marshmallow bunnies. He was supposed to draw a T chart then list the things he knew on one side. On the other side, he’d write what he needed to find out.

Later I made my own T chart. On one side, I listed the things I know are not possible. On the other, I noted the things I’ve discovered, things I didn’t know were possible until this last month that’s felt like a year.

First, what I know I can’t do. I cannot go for a walk when I feel overwhelmed. I can’t take up running. I haven’t listened to a podcast. I’m limited in hands, patience and emotional fortitude. I have not baked bread or curated science experiments involving food coloring. My kids are not learning math with measuring cups. Virtual tours demand coordinated attention spans. So do stained-glass driveway chalk projects. I can’t go to the grocery store with three kids, nor can I leave them at home. I can’t learn new recipes. There are zero home workouts happening, and we eat an unfathomable amount of carbs.

There’s a meme I can’t seem to escape: “Don’t complain about staying home, be grateful about who you can stay in with.” For frontline families, whose loved ones work at hospitals, grocery stores, on delivery trucks, this is complicated. We’re grateful for so much — of course we are. But our frontline workers are part of what makes home, home. We miss them. We’re scared for them.

Advertisement

[O]ur frontline workers are part of what makes home, home. We miss them. We’re scared for them.

Once I fell apart seeing a family walk down our street, as my husband drove away. Then I saw a blog post about keeping the spark alive in quarantine. Are you kidding?

Still, there’s the other side of my T chart. Here are some things that I didn’t know were possible a month ago.

It’s possible to connect with someone through a second story bathroom window. It’s possible to send a friend an entire grocery list. Every week.

A village can make you feel whole, even when you can’t see the people in it. I have a beer fairy: she leaves boxes of IPA on my porch. I pay my house cleaner not to come, and she drops off toilet paper. Friends leave dinner in a cooler for my husband every night that he’s away from us. We FaceTime at dinner, and the kids love watching him reheat chili on the boat's tiny kitchen stove.

It’s possible to tell friends I didn’t even know a year ago that I love them.

New rituals are important. Mornings can start with a text thread: a daily coronavirus haiku and mental check ins. It’s possible to create a ritual of watching “The Simpsons” at dinner every night when I have no words left for my kids. We’re on season three; there are 30 to go. That’s a lot of dinners.

It’s possible to cry at breakfast, then still have a pretty good day.

It’s possible for my 10-year-old to see that parents are human. It’s possible for my son to stonewall Zoom school, as long as he watches Jarrett J. Krosoczka’s daily drawing lessons and makes comic books with religious fervor. There are many ways to learn. My 3-year-old walks around the house muttering a curse word he learned from my dad — who we can’t visit — and I find it bizarrely comforting.

It’s possible to cry at breakfast, then still have a pretty good day. It’s OK to tap out from fear and anxiety, and cry from kindness instead. Yesterday I teared up over toast while we watched the cast of Hamilton sing for that 9-year-old girl. I opened a note from my grade school teacher and lost it again. My kids see my cry, and they see me laugh. They learn something from both.

That second-grade math problem? We were off by 5 cents. We turned it in anyway.

This segment aired on April 16, 2020.