Advertisement

Commentary

As She Battles COVID-19 Alone, My Mother Has Become Another Face In The Window

Yesterday I visited my mother. By this, I mean that I stood on the little mound of grass outside her nursing home’s entrance and gazed up at her, a shadowy figure in a fifth-floor window, as we talked on our cell phones. My mother has COVID-19 and has been quarantined in an isolated wing of her residence, so this was as close as I could get to her.

We spoke for only a few minutes, because as happy as she was to see me — I could hear the smile in her voice — she tires easily and needed to get back into bed. Her fragile 92-year-old lungs are battling the pneumonia so typical of this monstrous virus, and she grows more fatigued by the day. When we waved to each other and said goodbye, I felt the same mix of fear and longing I remembered while waving to another face high in a window many years ago.

When my brother and I were very young, he developed active tuberculosis and spent two years in a juvenile sanatorium just north of Boston. The two of us were Irish twins, my birth coming just 10 and a half months after his, and like most twins we were inseparable. When he went away, at not quite 3-years-old, I was too young to understand why, but his absence was an ache that grew deeper over time. Much of that enduring discomfort, I now know, came from the cataclysm I could feel ripping into my family, the fear and grief my parents tried to contain but that filled the very air I breathed.

Although TB was an ancient scourge, successful treatment was barely on the horizon in the mid-1950s, and the drugs my brother was being given had potentially devastating side effects. To die from this disease was still not uncommon.

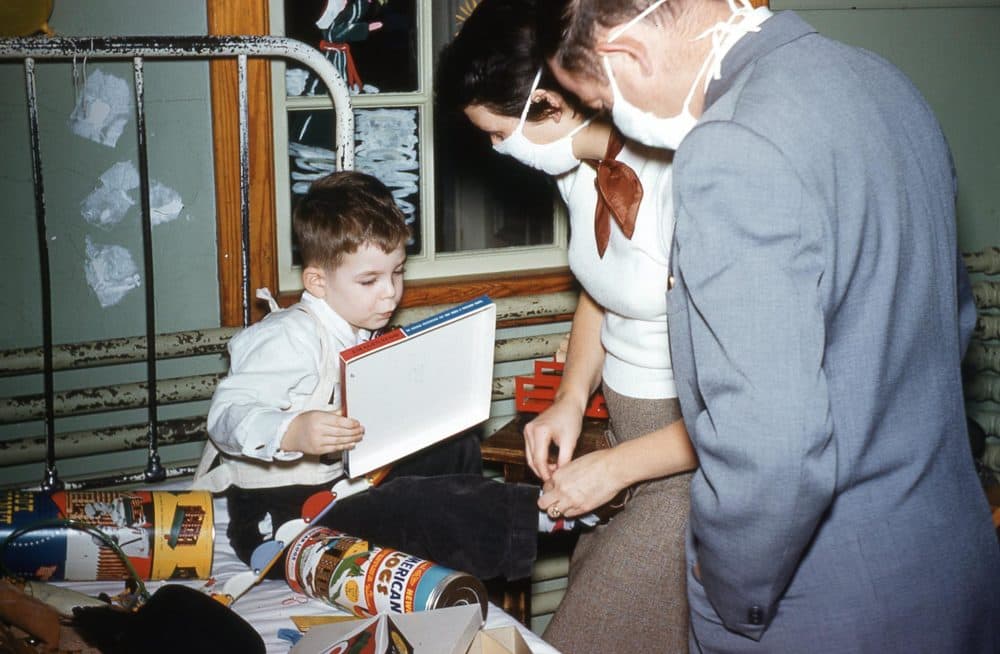

For months, my brother was quarantined in his room, harnessed and strapped to his bed, as were all the other young patients in the rooms around his. My parents were required to wear surgical masks for the duration of every visit. Whenever I’ve looked at the few photos we have from that time, I’ve wondered if my brother could see the sorrow in their eyes — their only features visible to him — as he looked up at them from his bed.

I couldn’t see whatever was in my brother’s eyes the one time that I, too, got to visit him; perhaps they were shimmering with fever, but I was too naïve, and too far away from him, to have noticed such a thing.

It was a sunny spring afternoon, I remember, the grass as deep green and luxuriant as the grass I stood on just yesterday. I wasn’t allowed inside the hospital, so I waited outside with my mother while my father brought my brother to his window.

When he saw me he broke into the biggest smile I’d ever seen, his hand waving with such energy that it was hard to believe he was sick. My heart filled my whole chest as I smiled and waved in return. My father opened the window so my brother and I could call back and forth to each other. I don’t remember what we said; his face in the window, the proof that he still existed, was the only thing that mattered. For those few minutes, all the bad feelings fell away.

Then the window closed and we drove back home, the place where uncertainty lived.

I don’t remember what we said; his face in the window, the proof that he still existed, was the only thing that mattered.

For the next 18 months, my mother and father swung between hope and dread as my brother’s condition seesawed between improvement and relapse. My parents weren’t the only ones who were afraid; anxiety about contagion infected their entire world, spreading among their friends, our neighbors, even our extended family until our house became the place that nobody wanted to enter. I hunkered down inside it, playing with our Tinker Toys as I waited for my brother to come home — my parents had promised that someday he would — and yet knowing from their faces, from the feeling in my stomach, that he might not.

I have that same feeling now as I wait, in our suspended world, for whatever is coming: the possibility that my mother will survive but the likelihood that she won’t; the unspeakable cruelty of her death, if it comes now, while she’s alone in a room with no loved ones by her side; the possibility of my own premature death, or of my husband’s, my friends’, even my children’s; life on earth turned upside down in ways I can’t yet see but can already feel. However the pieces land, some of them will be gone forever, just as pieces of my brother were gone when he finally came home to us — just as my family was never the same again.

For now, I'm gazing up at that face in the window and listening to the voice in my ear.