Advertisement

Commentary

I’m A Black Woman And A Medical Student. I Know Public Health Can Be Lethal For People Of Color

I love to run. To my family’s surprise, I’ve run two full and seven half-marathons over the past three years. For them, running seems like a chore, but for me, it's my happy place.

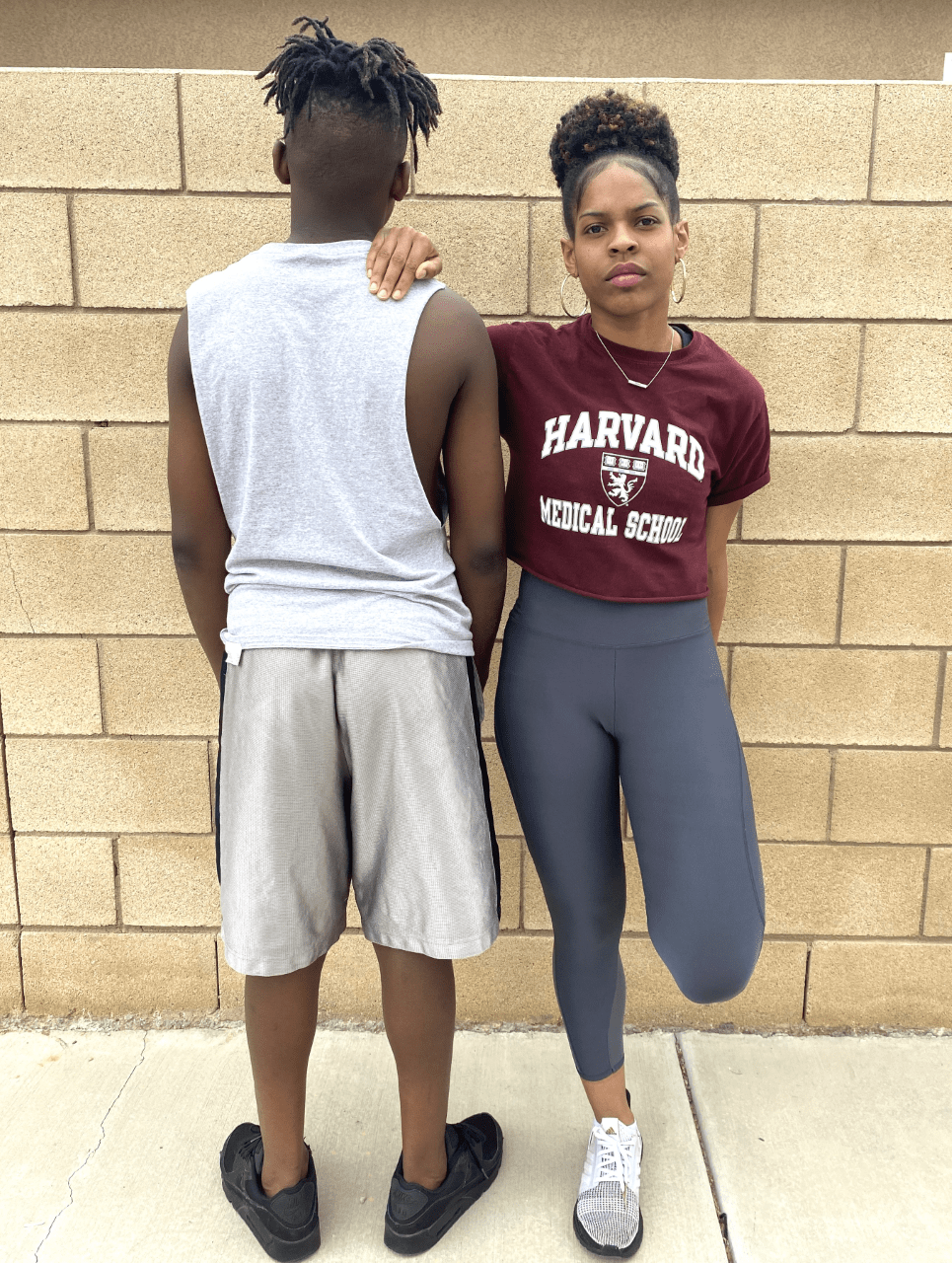

Due to COVID-19, I moved back home and have since introduced my 12-year-old brother to the joys of running. It’s been my way of showing him how to protect his body when so many systemic inequities seek to harm it. I thought I was protecting him, but last Tuesday, America proved to me once again, black people aren’t safe in this country — not even when engaging in acts of self-care.

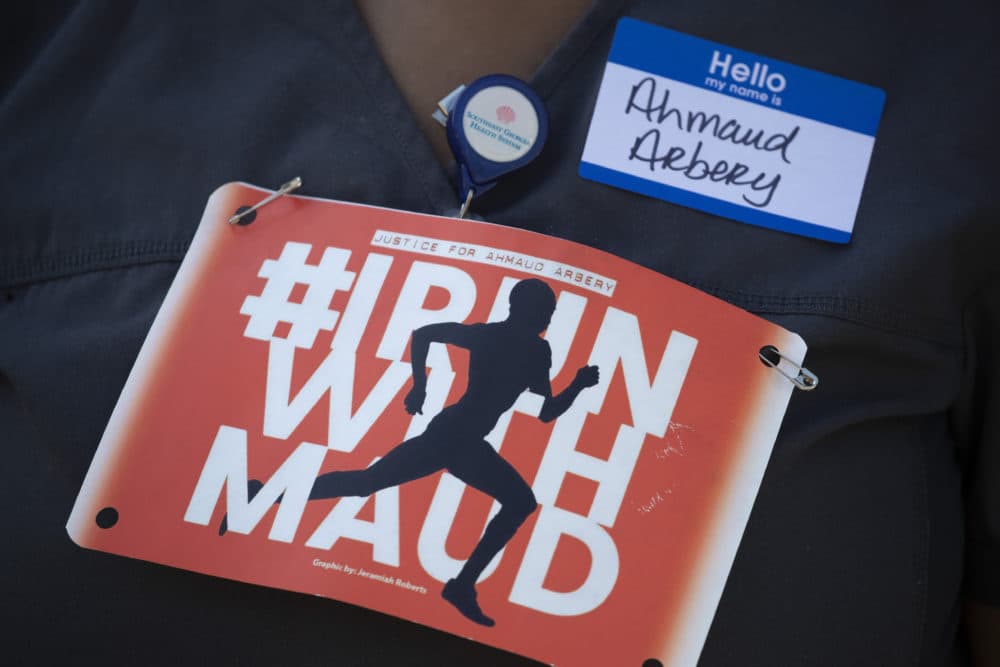

On Feb. 23, 25-year-old Ahmaud Arbery decided to take a jog around his neighborhood in Brunswick, Georgia. A former high school football player, he — like me — ran to stay healthy. He couldn't have known that his attempt to care for his body would turn fatal.

As Ahmaud ran by Gregory and Travis McMichael, father and son, the two men grabbed their guns. They chased him down in their truck, assuming that he was responsible for a string of burglaries in the neighborhood, according to the police report. A leaked video of the shooting shows Arbery running around the truck, past a man who stood in the back, holding a pistol. Another man beside the driver's door held a shotgun.

In the video, a shot is heard and Arbery and the second man seem to be wrestling over the gun. Two more gunshots. Arbery tries to run away but staggers and falls face-down on the street. His futile attempts to break free couldn't match their loaded guns.

That Sunday afternoon, Ahmaud Arbery was lynched. The entire act of violence was recorded and shared with authorities, yet they took over two months to arrest his alleged killers. His justice would hinge on the release of a traumatizing, graphic video on social media and a national public outcry and demand for justice.

I continue to be deeply unnerved by the killing of Ahmaud Arbery. As I watched the gruesome video, I imagined my brother and myself on the other side of the screen. It could have easily been either one of us — or any young black person in America with the audacity to exist.

I exist as both a medical student and a black woman in America. I regularly meld these identities in my activism for social justice and health equity. But in moments like these, my identities are at odds with one another.

The day after I watched the video, I was learning about pancreatitis. I managed to study and complete my assignments. But I simultaneously found it difficult to think like a medical student as I grieved in silence as a black woman. So many questions ran through my mind.

What would have happened if the video hadn't been leaked? If #AhmaudArbery never became a trending hashtag? If this local murder never made news outside Brunswick, Georgia, leaving Ahmaud to become a statistic, alongside the other 531 black people who were lynched in Georgia from 1882-1968?

In the past two months, I have been equally saddened by the disproportionate infection, mortality and arrest rates of black people across the U.S. as a result of COVID-19. I believe the systemic racism behind the killing of Arbery is the same scourge that has caused the extensive suffering of black people during this pandemic.

I understand this to be true because of the double consciousness I employ as both a black woman and a medical student. But this understanding shouldn't be unique to people of color. Regardless of their background, all health professional students should be taught and understand the inextricable nature of the biological and the sociological as it relates to medicine. While we are making strides in the right direction, we still have far to go.

We’re taught to encourage our patients to wear masks, without fully understanding the history of criminalization of black men in America.

Now, much social justice teaching in medical school is limited to optional lunch talks, student-led initiatives, and short-term community engagement. This is often coupled with awkward conversations about implicit bias and health disparities statistics shown at the end of lectures without context. The killing of Ahmaud Arbery and the tragedy of COVID-19 ought to demonstrate the importance of context.

Medicine and public health save lives, but without historical and sociological context they can be paradoxically lethal. As students, we’re trained to tell our patients to exercise. But we must also learn that running outside while black might be more dangerous than not exercising at all. During COVID-19, we’re taught to tell our patients to social-distance. But it is critical we also learn that for black and brown patients, this may be impossible due to overpopulation driven by racist housing policies. We’re taught to encourage our patients to wear masks, without fully understanding the history of the criminalization of black men in America.

All taken together, this is a deadly cocktail that puts black and brown patients at risk. The responsibility to understand and teach this inseparable connection should not solely lay in the hands of students of oppressed identities, but it should be a collective value of all institutions that seek to preserve the health of our society.

Ahmaud Arbery, like my brother, deserved to run freely without fear his melanin will be equated with danger. Unfortunately, racism is deeply sown into the soil of this country and it might take decades to destroy its stubborn roots. But now we do have the power to teach future health professionals that not all public health advice is created equal — an effort that will demonstrate that we, too, can #RunWithMaud but it will take much longer than a day.