Advertisement

Commentary

I'm A Parent And An Educator: The Pandemic Will Widen The Achievement Gap Into A Chasm

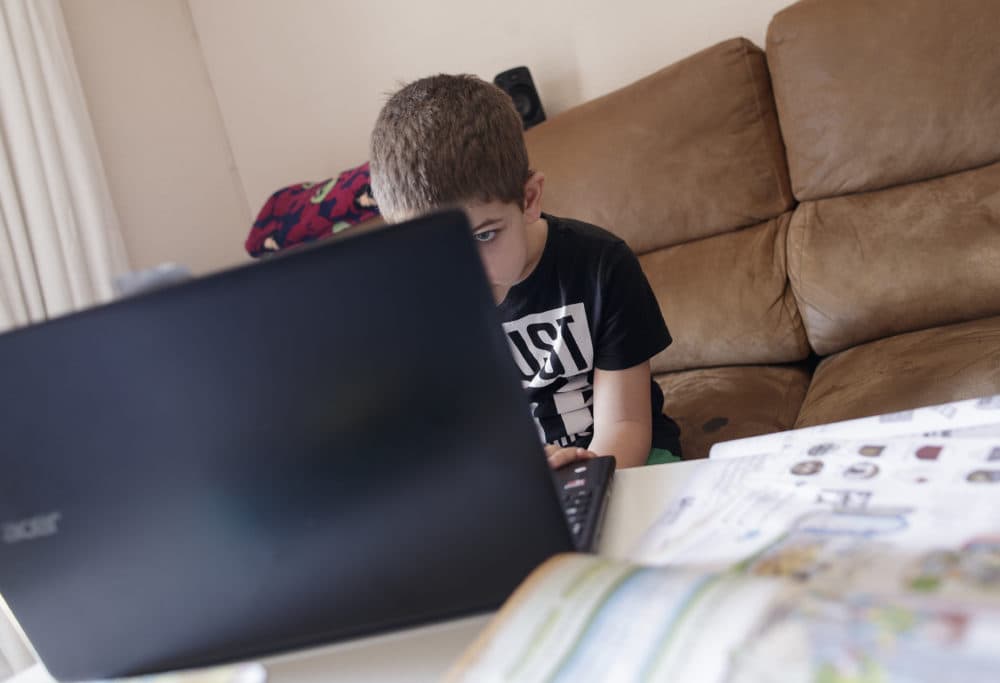

My 7-year-old son refuses to do the worksheet. He is a bright, temperamental kid. A precocious reader, musician, poker player. Until last month, he always loved school.

Today’s assignment: cut out verbs ending in –ed and glue them onto a chart to classify them by sound /d/ /t/ and /ed/. When he shakes his head, I can’t blame him. This kid knows the past tense: he can repeat verbatim stories his grandmother tells from her own childhood in Guatemala City, how she used to buy pan dulce in the market for two quetzales and sell them back into her neighborhood for three.

Listen, I say. Just get this done. It will take five minutes. He sighs, picking up the worksheet.

What I’ve learned these last couple months of homeschooling: my son hates using scissors, and he gets frustrated easily. Sure enough, one errant cut and he starts crying. I try to comfort him. But it’s too late and now he is shouting. Take some space, I say. Come get me when you’re ready. On my way out the door, I can’t resist a final word. But you will finish this assignment.

The pandemic did not create these problems. All it has done is laid bare the inequalities built into our society from its very inception.

I tell myself it’s a muscle he needs to keep flexing, doing what the teacher says. One thing I’ve learned about surviving these surreal times is the importance of routine; in our house, if we don’t get dressed, brush our teeth, and get started on work or school, everybody falls apart.

But there is also this: my son is an interracial kid who presents as Latino, and as he grows older I fear how the world may interpret his refusal. And so I insist, waiting outside his bedroom door. Downstairs, my wife is with our toddler, the two of them laughing and banging on the piano, and through the door I can hear my son crying, and I am filled with doubt.

We are among the lucky, I know. My wife and I are both able to work from home. Our home has enough space. Space for our oldest son to read a book in the living room while his little brother runs around screaming in the basement. We are both longtime educators, so we know how to plan out a day of learning activities, how to vet learning apps, how to turn pasta into sensory play. We have enough food that we can treat it as a plaything. We have enough.

I think about people in our family who work in retail and construction, who clean houses, all of them staring down the barrel of uncertain months without income. I think about relatives in Guatemala, where the price of masa has doubled, which means people are going hungry. I think about friends who work in medicine or other essential fields, living in their garages or even sending their kids out of state as they face down death every day. And I think about the thousands of families I have worked with over my decades in urban education, about single parents struggling to pay the bills, risking their lives to hustle as Instacart shoppers or Amazon delivery drivers, doing whatever they have to do to keep food on the table. I think about the kids I’ve taught who live in shelters, who share an apartment with multiple families, who have the kinds of social-emotional and learning needs that could never be met by a screen.

I think of all of them, and I am terrified.

These days, in my work as an educational consultant, I meet with school and central office leaders in urban districts, and they come to their webcams exhausted from long hours distributing chrome books and meals, reaching out to students and families who are isolated or scared or grieving.

The other day, the principal of a middle school that serves an immigrant, working-class population told me that according to their internal metrics, less than 25% of their students are doing the lessons teachers send home. I get the context; students busy taking care of siblings, without a dedicated device or space to work or wifi, unable to get the support they need. And I get the consequences, too; by the time in-person classes start back up again, the achievement gap will be widened into a chasm. Over the years, I’ve seen what can happen after even a couple of months off for summer, when affluent kids attend robotics camp or drama camp while their less fortunate classmates flip burgers or stock shelves. And now we’re looking at a much longer stretch of time.

These are the thoughts that keep me up at night.

When I consider our boys, with their desk chairs and iPads, their Lego sets and finger paints, their stocked cupboards, I know that despite moments of struggle, they will come through this thing fine. But this will not be the case for far too many. And I know this is not accidental; it is the result of a long history of racial and economic injustice, from policies such as redlining to school segregation to discriminatory practices in employment and healthcare, all of it adding up to a system designed to maintain power for people who look like me at the expense of people who look like my son.

The pandemic did not create these problems. All it has done is laid bare the inequalities built into our society from its very inception. Because to be honest, it isn’t precisely luck we’re talking about here, is it? It’s privilege. It’s structural racism.

These are the thoughts that keep me up at night.

Those of us who call ourselves lucky have a responsibility to name this injustice, and to dismantle it. In this moment in history, as the machinery of our economy is frozen and we are forced to rethink the social contract, to reimagine our schools and workplaces, we have a unique opportunity to do better. If our government is going to spend trillions of dollars, we must hold our lawmakers accountable to spend those funds on working families, not just corporations. And as we shelter in place, figuring out how to educate our own children as we make it through the day, we have an opportunity to do better as well.

None of this is easy, of course. And I still don’t know if I am making the right choice, forcing my son to complete the damn worksheet. All I know is this: I am flooded with relief when, after 10 minutes of crying, he opens his bedroom door, reaches out for a hug, and asks for help.

I hold him tight, rocking him back and forth in my arms, telling him everything is going to be OK. I try as hard as I can to believe it.