Advertisement

Commentary

For Black Americans, 'Social Distancing' Is Nothing New

A mere three or four months ago, most of us — except those who work in health and medical professions — never uttered the phrase, "social distancing." Now, with the onset of COVID-19, it's become part of our everyday language.

But for black Americans, social distancing is nothing new. Our version has a different meaning from the one the country has recently learned. We've long practiced social distancing to keep ourselves safe and lessen our chances of a shortened life span: not because of a contagious disease, but because of racism.

And so we social distance. For 10 years I have lived in the condo unit that I purchased in a city 20 miles south of Boston. Yet, when I walk across the parking lot to put trash in the dumpster, I sometimes hear the clicks of automatic door locks. After my husband and I got married and he moved in with me, I noticed that he would linger in his car when he got home from work. He told me that if a white woman was in the parking lot, she would likely break into a sprint if she saw him — even at a distance — behind her. So, he routinely stays in his car listening to the radio or counting up loose change until all is “clear.”

We've long practiced social distancing to keep ourselves safe ... not because of a contagious disease, but because of racism.

I have experienced white women suddenly clutch tightly onto their purse straps as I’ve walked past them on the sidewalk. Some have begun to visibly shake, their eyes growing wide, as if terrified, if I happened to make eye contact with them in an elevator. Numerous times, I’ve been followed around by staff in clothing boutiques as I shopped.

I enjoy taking long walks in a park not far from where we live. As a precautionary measure, I keep my distance from white individuals on these walks, slowing down or lingering a little longer on a footbridge overlooking the pond, if necessary. In the supermarket, I steer clear of shopping carts in which women have left their purses unattended as they peruse the shelves.

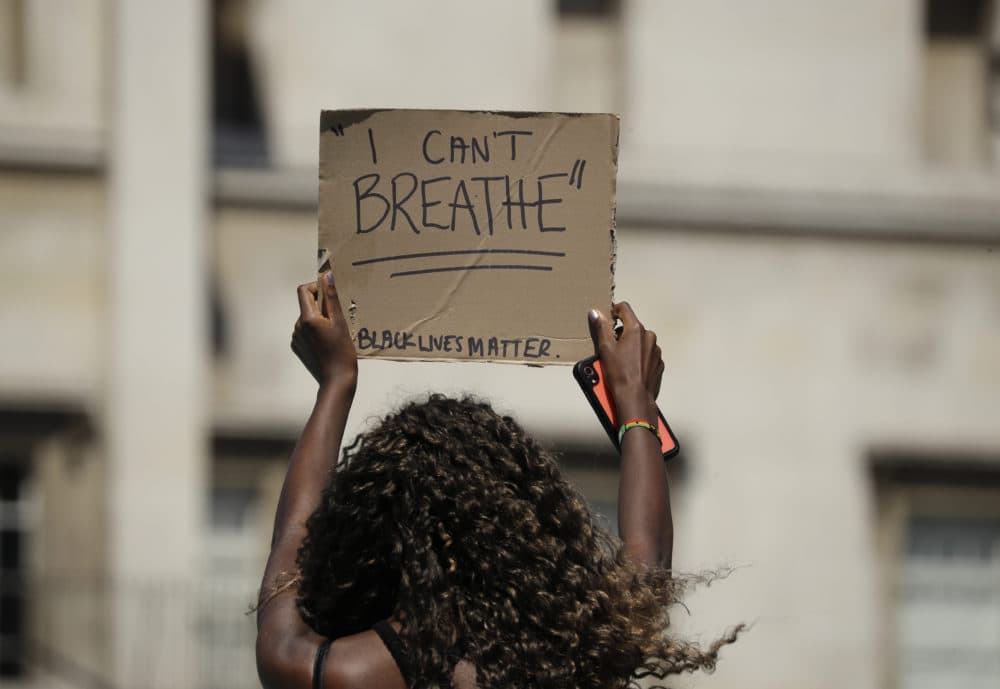

I have followed the news accounts of George Floyd's brutal killing by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin. I am outraged by the images of Chauvin pressing his knee into Floyd’s neck while one of his hands appears to be tucked casually in his pants pocket. I can’t bring myself to watch the video. My husband did, and described to me how excruciating it was to hear Floyd beg for his life and say, “I can’t breathe … please stop.” I knew that if I viewed it, I would become ill.

I have experienced white women suddenly clutch tightly onto their purse straps as I’ve walked past them on the sidewalk.

The horrifying attack on Floyd, the agitated police call on birdwatcher Chris Cooper, the shooting death of black jogger Ahmaud Arbery, the police killing of Breonna Taylor, and all other recent assaults and killings of innocent African Americans are an all-too grim reminder: to many, people with black or brown skin are a threat simply because they exist.

That same mentality embraces the idea that black and brown people can and should be controlled, manipulated and suppressed at will because the system is on the side of those who seek to control, manipulate and suppress. Those people believe that attacking them or snuffing them out is permissible, and sometimes encouraged, as a solution to easing their discomfort with us and assumptions about us.

I have grown tired of the unfair and inaccurate assumptions made about me. Living this way is exhausting and offensive. Neither my husband nor I wants to be harmed. Both of us fear that we will because of these incorrect assumptions.

Advertisement

Sometimes late in the evening, my husband has a craving for a chocolate candy bar. He’ll drive down to the main road and if he sees a police car go by, he’ll turn back, not wanting to get caught in the crosshairs of some activity that has nothing to do with him. I’m relieved that he does this. Other times, if he’s gone too long, I worry. I’ll wonder if he got to the little variety store safely or if he’s been harassed or harmed.

This is no way to live. But it is our reality and that of so many others. America is burning and it’s no wonder. Recent deadly acts of violence against the innocent reaffirm that racial progress doesn’t seem to be in the distant future. It doesn’t seem to be a possibility at all.