Advertisement

Commentary

I Want For My Black Sons, What My Mom Wanted For Me: To Be Seen As Fully Human

Editor’s note: Watkins began this essay as a letter to his mother. He started writing and just kept going. “Maybe I’ll share it with her one day,” he told us.

My mom grew up in the “real South,” in the Mississippi Delta, down the street and around the corner from where Emmett Till and so many Black people had their lives taken from them. I spent a lot of my childhood, summers and vacations there, too. Mississippi is big part of my identity and my roots.

Even so, I never quite related to all of my mom’s over-protection from white people. She bore a deep distrust I couldn’t fathom.

I grew up a military kid — enlisting to fight for his country is how my dad made a life for his family. So, at an early age, I was exposed to lots of different kinds of people. But I remember when I brought my first white friend home to visit, and gushed about how great he was. Mom gave me the side-eye. “Mom, they are human beings. We are human beings,” I said.

“Keep living, son. Keep living,” she replied.

My mother bears no ill will towards white people. But with all she saw growing up — and what she keeps seeing — she’d put that side-eye on you.

Black folks know what I’m talking about.

By all the measures we count, I am successful — an entrepreneur, a philanthropic leader, a husband, a father, a husband to an amazing mother and scholar. But I have been reminded these last two weeks (as I have been so many times before) about the glaring brutality of America.

It’s the realization of how much pain my mother and her mother must have carried, thinking about the danger that their Black children faced.

We are a country that incarcerates Black men at five times the rate of whites; a nation that allows people who look like me to be strangled by a white policeman in broad daylight, as casually as someone might smoke a cigarette.

The last few days, whenever I think of George, Brionna, Eric, Ahmaud, Trayvon, Alton, Philando, Tamir, and look at my little boys, I tear up. It’s the pain of thinking that other people don’t see my sons as people. It’s the realization of how much pain my mother and her mother must have carried, thinking about the danger that their Black children faced.

Try adding that pain and fear up over generations and generations. That’s a lot of pain; a lot of tears and fear. It’s frustration and anger that white people don’t even have to think about.

I want to tell my mom, I get it. I know what she was saying all those years ago; she was saying that some white people don’t see Black people as fully human. I see it in the raised eyebrows when people are shocked to learn that my Black wife is a tenured business school professor or share some other accomplishment that might, in their minds, be reserved for someone who doesn’t look like us. I am reminded of the numerous times I have personally been subjected to police aggression and violence.

Advertisement

I’m crying as I write this, and my tears have turned angry. I’m thinking of all the terrible things I would do to anyone who would try to hurt my sons. My beautiful boys.

Sometimes, when white people tell me how cute my boys are, I get angry. I know they mean no harm — my boys are adorable — but when you are Black and have received signals your whole life that you are not human, my brain translates “cute” into “like a puppy.” This is what 40-plus years of scars can do to a person.

I lead the program team at The Boston Foundation. A few weeks ago, I was in a meeting, speaking passionately about why philanthropy must do more to value the lived experiences of the communities we serve. The response was, “tell us why that’s so important?”

Deeply embedded in our subsequent conversation, was this sentiment: poor Black and brown broken people don’t have the ability to solve their own problems. There’s no doubt the people in that room are eager to protect the less fortunate. But even among those well-meaning people, there is this question about Black people’s capacity.

Mom, I get it.

I’ve spoken and emailed with countless Black friends and colleagues over the past several days. Every conversation results in a level of frustration that ends in tears. It’s debilitating. One friend told me, “I never cry, but now I can’t stop.”

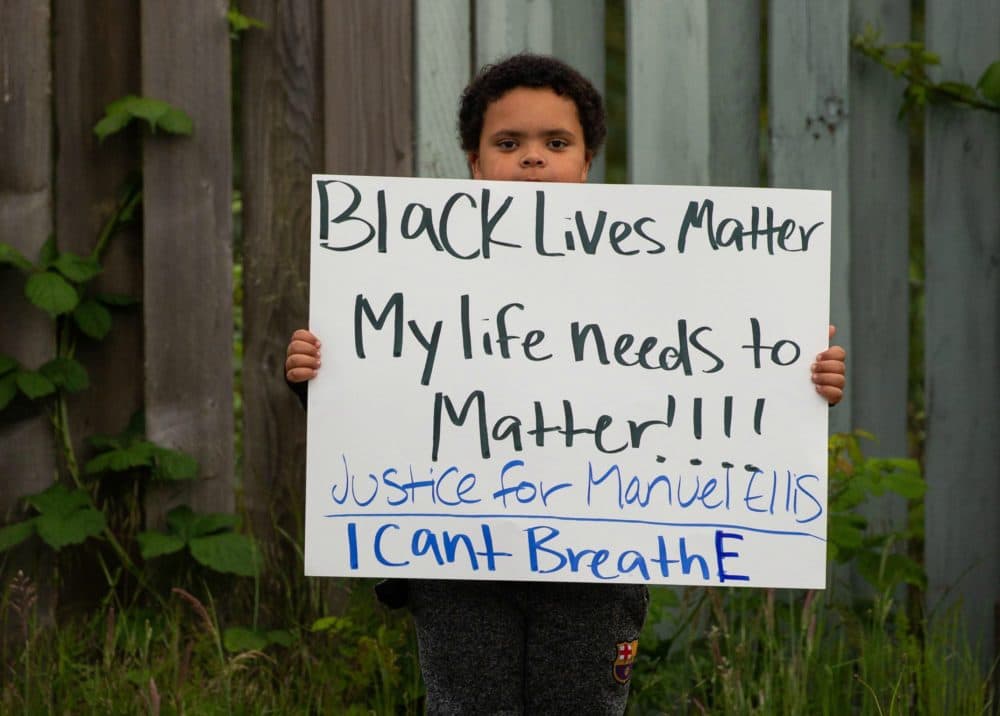

I want you to see me. I want you to see my boys -- to really see them. Can you?

I’ve read all the parenting stuff. I’m trying to remember my history, Dr. King and John Lewis and Andrew Young. I’ve propped up my boys. I give them hugs, so many hugs.

My younger son, Max, is 5. He’s got a devious little smile — I can imagine him popping off to some police officer about his constitutional rights one day. I love his spirit. Should I crush it? If you’re white, you think, that kid is destined to be a lawyer. If you’re Black, you think how do I protect him from himself? His beautiful strength, his spirit, his spark — it’ll give him everything he needs in this world, and it could kill him.

Despite all my mom and dad have experienced, they’ve maintained hope and commitment to their children, and a belief that this country can and must be better for their grandsons. It is amazing how much fight and resiliency Black folks have.

Damn, I’m crying again. We’ll keep fighting but I am exhausted.

The violence that surrounds us; the constant devaluing of Black bodies.

I want you to see me. I want you to see my boys — to really see them. Can you?