Advertisement

Commentary

What We Can Learn From The AIDS Crisis In The Race For A COVID-19 Vaccine

The U.S. has a multi-billion dollar initiative underway to develop a COVID-19 vaccine and its accompanying 300 million doses, before the end of 2020. The initiative is called “Operation Warp Speed” and it’s placing big bets in the form of investments.

Thus far it has identified, as finalists, five companies that are developing vaccines, including four U.S.-based companies and an alliance between Oxford University and AstraZeneca, a UK-based pharma company.

In the best case scenario, scientists suggest a vaccine may be available in 12 to 18 months. The high-stakes vaccine race is on, but with an all too familiar twist: Who will get access to it?

A scientist working for the U.S. government said that vaccines developed with the support of Operation Warp Speed will be for U.S. citizens. But Oxford/AstraZeneca committed early on to “broad and equitable supply of the vaccine throughout the world, at no profit” -- even though they’ve already promised their first vaccines to the UK and the U.S., the highest bidder.

The winners of the vaccine race could end the pandemic by vaccinating the world’s most vulnerable, and then everyone else. Or they could do what drug makers do: sell to the highest-bidding countries, which will limit distribution to those with insurance to pay for it. That is no way to end a pandemic.

The high-stakes vaccine race is on, but with an all too familiar twist: Who will get access to it?

There’s much to be learned here from the AIDS crisis. I tested positive for HIV in 1985. Soon after, I joined ACT UP Boston. In the 1980s and 90s, as the pharmaceutical industry failed to develop drugs to treat AIDS, and as the government refused to let us distribute explicit safer-sex information, ACT UP demonstrated.

ACT UP forced the government and the drug industry to radically change how they conducted drug research. On September 14, 1989, ACT UP took over the New York Stock Exchange to protest Burroughs-Wellcome’s pricing of the first AIDS drug AZT — the most expensive drug ever. ACT UP activists blew fog horns to drown out the opening bell. Within weeks, and after intense media shaming, Burroughs-Wellcome reduced the price of AZT.

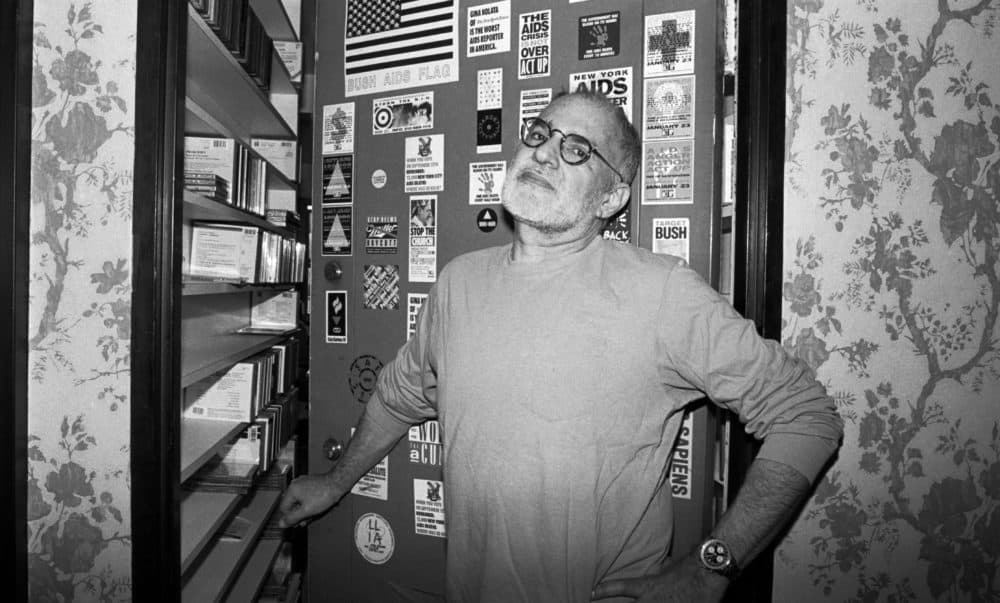

Larry Kramer, the founder of ACT UP, died on May 27. As we honor his life, we can also celebrate how his loud-mouthed militancy spearheaded ACT UP’s success.

Larry said, “Unless we fight for our lives, we shall die”-- and fight we did.

I grew up in the Catholic Church. At ACT UP die-ins, where we were protesting the Church’s opposition to safer-sex messages, I could pretend to be dead — as so many of my friends were from AIDS. I laid on my backside alongside the living, glad to be blocking rush-hour traffic or distressing parishioners who were departing mass. We wouldn’t be ignored.

Larry cared deeply about COVID-19. In one of his last interviews, Larry told the New York Times that COVID-19 called for its own Larry Kramer, but unfortunately, it would not be him. We can honor Larry’s moral courage by fighting for equitable access to the vaccine in the U.S. and globally.

We can honor Larry’s moral courage by fighting for equitable access to the vaccine in the U.S. and globally.

The age-old questions that determined the early response to AIDS are being answered today about COVID-19 in similarly tragic ways: whose lives matter, who must be saved and who is expendable?

In late February, Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar told a congressional committee that “The priority is to get vaccines and therapeutics. Price controls won’t get us there.”

And on June 9, Dr. Anthony Fauci reinforced this opinion that price controls “would probably not help.” In his opinion, they would only scare away vaccine companies. But I doubt it. We’re one of the only countries that doesn’t negotiate with pharmaceutical companies over drug and vaccine prices — we tolerate what other countries won’t.

Globally, the situation appears even more bleak. If China or the U.S. become first to develop vaccines, strong nationalist tendencies in both countries may mean global access to the vaccine could be unlikely. Partnership between the two countries also seems unlikely.

Advertisement

A global pandemic requires a global response, right? Groups including the WHO, the European Commission, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovation, Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation and the Gates Foundation support efforts to fund, develop and distribute vaccines globally. But the current U.S. administration isn’t interested.

Avram Finkelstein, an artist and another founder of ACT UP, recently told me, "If we're not engaging in activism to fight for national and global access to COVID-19 drugs and vaccines, we're tacitly participating in the death and suffering of those who fall ill."

In the end, this truth — that if I don’t participate in the fight, I’ll be responsible for the devastation from COVID-19 — remains my most important lesson from Larry Kramer and ACT UP.

Ongoing nationwide protests in the wake of George Floyd’s killing by a Minneapolis police officer demonstrate that direct action, as ACT UP did, is still possible. On May 20, activists representing the Center for Popular Democracy, Indivisible, National Domestic Workers Alliance and MoveOn staged a mock funeral procession of over 200 cars and placed body bags, labeled “Trump Lies People Die,” outside the White House.

If our elected officials won’t ensure equitable, moral access to national and global life-saving vaccines, we must demand it.

One campaign fighting for global access and a free vaccine, Free the Vaccine, represents 29 countries and two organizations, Universities Allied for Essential Medicines and the Center for Artistic Activism. Another is Lower Drug Prices Now, a U.S. coalition of nearly 60 social justice organizations.

My greatest hope is that when vaccines do arrive, they’ll be available first to those at greatest risk. In the U.S., that’s the elderly, the underinsured, the incarcerated, the homeless, the working class, health-care workers and first-responders, immigration detainees, racial minorities and those with high-risk medical conditions.

If our elected officials won’t ensure equitable, moral access to national and global life-saving vaccines, we must demand it.

Let the words of Larry Kramer be our guide: “Own the bigness of who you are, and you can and will change the world.”